Book Review – The Blunting of the Snark

The two books this month raise questions of when to be or not be contentious. One goes out of its way to be controversial as it can be, but comes off as brattish and self-defeating. The other tries to avoid controversy, but manages to create it.

First up is Mark Gardiner’s Bathroom Book of Motorcycle Trivia: 360 days-worth of $#!+ you don’t need to know, four days-worth of stuff that is somewhat useful to know, and one entry that’s absolutely essential (2012). Gardiner is best known for Riding Man (2006), his memoir of his Quixotesque quest to race in the TT. In addition to monthly columns in Classic Bike and on the www.MotorcycleUSA.com website, he blogs at www.Bikewriter.com. Gardiner also produced at least two other motorcycle books: Classic Motorcycles (1997) and BMW Racing Motorcycles (2008) with Laurel Allen. As a bibliography, that’s anything but trivial.

Trivia is an odd genre, if it can be called a genre. The pleasure of a good bit of trivia is like Oscar Wilde’s cigarette: It is exquisite, and it leaves one unsatisfied (The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890)). The piece of trivia has to be accurate and should be amusing. It is history as a random collection of unrelated anecdotes.

Here in the States, the apogee is either the television quiz show, Jeopardy, or the now classic board game, Trivial Pursuit. In those two cases, the trivia answer, whether in the form of a question or not, has the effect of a kicker or punch line.

That isn’t to say that a bit of trivia can’t be longer than a tweet. Certainly the two have some elements in common: fun, brief, credible, entertaining, and occasionally funny, to use a handful of elements that Sree Sreenivasan lists as the attributes of a good tweet. Sreenivasan, Columbia University’s first Chief Digital Officer and professor at Columbia’s School of Journalism, teaches a popular extension course in social media for writers and journalists. The list also includes timely, useful, helpful, generous, relevant, practical, actionable, and informative. A good tweet, Sreenivasan stresses, should have one or more of those characteristics. A good tweet is often a good bit of trivia.

The Darwin Awards (www.darwinawards.com) is an entertaining example of longer trivia. Its stock in trade is a sort of schadenfreude, being amused by accounts of people who, “In the spirit of Charles Darwin… protect our gene pool by making the ultimate sacrifice of their own lives. Darwin Award winners eliminate themselves in an extraordinarily idiotic manner, thereby improving our species’ chances of long-term survival”. Motorcyclists are directly or indirectly involved in at least a dozen tales of deserving award recipients.

Back to Gardiner and his bathroom shit: according to the forward, the book was originally commissioned by a small imprint. The publisher tried to screw Gardiner over the advance. Ultimately, Gardiner cancelled the contract (his legal right by that point). It took a couple of years for Gardiner to get around to publishing the book himself. And edit it himself, unfortunately. For the same reason that lawyers don’t represent themselves in court and doctors don’t administer to their own families, writers don’t edit their own work: the professional involved does have the critical distance necessary to achieve professional results.

The concept of a motorcycle trivia book of days is as good an organizing principle as any. He further groups trivia by subject: “America’s ‘Must-Ride’ Roads“; Top stylists and customizers; or The greatest road racers of the past 50 years. Typically, but not always, there are ten trivial items per category. Each category gets at least a paragraph of introductory matter. There is no index, table of contents, or page numbers (which is annoying, but not critical).

Despite that seeming structure, the book is a bit of a mess. The best “day” is probably 365: Last but not least, something that is not trivial at all: Staying alive. Trivial doesn’t have to be useless. This six page essay, although short, is not brief and is quite useful. Day 256 includes the provocative suggestion that riders wear a back protector as well as a helmet even if they are not racers (The point is undermined somewhat by an inappropriate product endorsement). The more-or-less four months-worth of days dedicated to races, racers, and racing are overall solid and readable. Gardiner likes Mike Hailwood, but can’t warm to Valentino Rossi. But then again, Hailwood, like Gardiner, did the TT.

There are the more expected lists of ten: ten best motorcycle movies – mostly documentaries about racing – and the ten worst – in which he includes The Wild One (1953). The problem with labeling a film that is better described as overrated than as bad is that it makes the more rational choices – Torque (2004), say, or I Bought a Vampire Motorcycle (1990) – sound better than they are. (To answer the question no one wants to ask, the vampire motorcycle – a Norton Commando, no less – runs on blood, not petrol.) He includes Peter Fonda and Dan Haggerty in his list of Top stylists and customizers, although they only customized one bike: the Captain America chopper in Easy Rider (1969). The film, incidentally, is also on his list of best motorcycle movies.

Once Gardiner leaves trivia about what he loves best – racing – and well-established sub-categories – movies – he gets into trouble, most of which is a mix of bad writing and bad editing. Days 171 and 182 are virtually the same anecdote: that the Harley-Davidson VR 1000 was homologated in Poland to comply with then AMA Superbike Championship rules and regulations. 2000 were sold. Day 202 features a great quote about why there is no apostrophe in Hells Angels, but credits it to an unnamed Angel. The quote is used on the official Hells Angels web site, which is not trivial, nor is it devoid of deliberate humor.

His retelling of T.E. Lawrence (of Arabia)’s death in a motorcycle accident for Day 61 is not only flat, but also misses the trivia fact that the attending physician was convinced Lawrence would have lived had he worn a helmet. The doctor went on to become one of the earliest advocates of what is now called mandatory helmet laws. Honda’s week to ten days has mostly obvious choices. It doesn’t include such trivia as the Nighthawk S (CB700SC), a destroked DBX750 that Honda created to get around import duties designed to save Harley-Davidson from extinction. The Motor Company was indeed saved. The Nighthawk went on to become a cult item.

Sometimes Gardiner hides more interesting trivia behind ordinary trivia. Days 205 and 207, for example, are part of a list of great American motorcycles from the past. A perfectly good concept: interesting in itself and likely to spark discussion, if not debate. The Neracar (205) and the Yale (207) are respectable candidates. The more interesting fact, especially in light of the recent revival of the vintage Motorcycle Cannonball Run (that was in part inspired by the records set by Cannonball Baker), is that he set one record on a Neracar. In the case of the Yale, way at the bottom Gardiner mentions that George Wyman made the first transcontinental trip on a motorcycle in 1903. A list of that sort of motorcycle firsts might have been more intriguing.

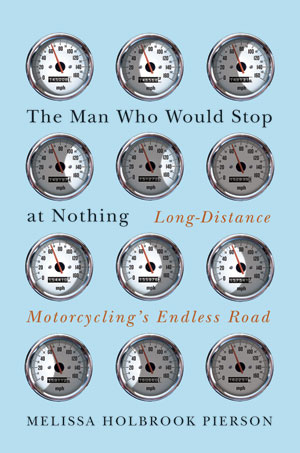

Worse in places the book is inaccurate. If the trivia isn’t true, its value is lost. It is also difficult to tell whether it is because of careless research, careless writing, or careless editing. For example, Day 292, part of a group of days dedicated to the best motorcycle books, covers Melissa Holbrook Pierson’s Perfect Vehicle (1997). No argument here since I would include it in the top ten motorcycle books to date as well. Gardiner, by way of putting Pierson’s book into context, adds, “Disappointingly, Pierson didn’t prove to be a lifelong motorcyclist… she abandoned two wheels and took up horseback riding for her next book and never looked back”.

Pierson published her return to motorcycling, The Man Who Would Stop at Nothing, a year before Gardiner published his book. At the very least, she did look back. Apparently, when Gardiner re-edited Bathroom Trivia for the 365 day concept, he didn’t bother to bring the manuscript up to date.

Nor is that case unique. Day 354 recommends The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Motorcycles, which he cites as being by “Motorcyclist magazine, Darwin Holmstrom, and Jay Leno”. The most recent edition of The Idiot’s Guide is 2011, also a year before the publication of Gardiner’s book. Furthermore, the author of record is John L. Stein. While it is perfectly permissible to favor an older edition to a newer one, which edition has to be made clear and reasons for the preference have to be given.

Parenthetically, I’ve never been able to determine what, if anything, Motorcyclist contributed to The Idiot’s Guide; our old pal, Darwin “Purpose-Built” Holmstrom seems to have done almost all of the heavy lifting in most of the five editions. Jay Leno only contributed a cover quote and a very funny introduction that was cut from the current edition. That intro is sorely missed.

It is probably more a case of careless writing than careless research that led Gardiner to claim that Kevin Cameron writes for Cycle magazine in Day 9. Cameron, inarguably one of the top ten writer/columnists in motorcycle journalism today, writes for Cycle World. Gardiner gets it right the second time he cites Cameron (Day 27) with the same quote about the same Suzuki.

The repeating of anecdotes aside, in citations, the first mention has to be complete, while subsequent mentions can be abbreviated as long as it is clear what the abbreviation refers to. For example, the first mention of The Rider’s Digest has to be complete, but any following mentions could fairly be The Digest.

The exception is when the original title is short enough (which would be the case here even if the order were correct) or when the work is not read sequentially. Unless the reader is a professional critic or has an advanced case of OCD, most readers dip into books about trivia at random, a page here, a chapter there, an order of fancy and serendipity, not editorial intent. Citations need to be complete within the anecdote.

Careless research and careless writing reach a nadir with Day 213. The trivia here is the sad sad end of the original Indian marque, used to flog Taiwanese-made mini-bikes. I didn’t know that myself, but interesting, if true. The catch is a sentence in the build to the kicker: “But it’s not great motorcycles like the Scout and the Chief we’re better off without, or even the Velocettes that Floyd Clymer imported as “Indians” in the early ‘60’s”.

Yes, but no. The Indians Gardiner is referring to are the Italjets, and there is considerable question about how much of the ultimate failure of the venture can be laid to Clymer’s death in 1970. About 100 bikes were produced with a Velocette engine. The date of the early 60s would be a few years too early for that. And what of the earlier Royal Enfields that were rebadged as Indians at roughly the same time Enfield was developing a separate corporate identity in India? Could Gardiner have been thinking of that, even if early 60s would be a bit late? Who knows, kemosabe?

Complicating the carelessness is Gardiner’s attempts at ‘snark’, which at best fall flat and more usually backfire, again because of careless writing. Gardiner is besotted with the word “trannie”, also spelt “tranny”. It can mean transsexual, transvestite, or, in Gardiner’s lexicon, transmission. Combined with an attitude toward women and gay men (not that he thinks there is anything wrong with that), it’s a disaster.

Day 37 presents Malcolm Forbes as one of the ten Entrepreneurs who made things happen. His contribution was to make motorcycling in general and Harley-Davidson in particular more acceptable to the mainstream, assuming mentions in social and gossip columns constitute acceptance. Regardless, his frequent companion, Elizabeth Taylor, was good for ink. Gardiner goes on to note that Forbes “was a closeted gay man who spent his night gay ‘bath houses’ that most mainstream Americans would have found utterly shocking”. There is a history of gay motorcycling – David Gross, Lawrence of Arabia, Dykes on Bikes, etc. – of which Forbes is a part like it or not, but here the reference seems prurient and gratuitous.

In the introduction to a section titled Things even “HOG” members don’t know about Harley-Davidson, Gardiner mentions that Arthur Davidson liked to go to parties dressed up in his wife’s clothes and to flirt with various men, kissing them when he could. It is also doubtful that most HOG members know that Davidson was a rabid anti-Semite, who insisted that at least one prospective employee prove he wasn’t Jewish. (Given Davidson’s proclivities, one doesn’t wish to know exactly how what evidence was submitted.)

While the warts-and-all approach to famous and important figures has much to recommend it, Gardiner’s comment about The Motor Company doesn’t: “[W]hile the museum has a room devoted to all of the different Harley motors, I don’t expect a room devoted to the Davidson trannies any time soon”. As if the implication that Arthur isn’t the only Davidson to indulge in a bit of friendly cross-dressing isn’t enough, we have the word “trannie”. Fortunately, the time period rules out transsexual. Unfortunately, it is pejorative.

“I always think of ‘trannie’ as being an annoying slang term and definitely derogatory”, explains Sybil Bruncheon, the founding Empress of the Imperial Court of New York as well as a leading drag performer and celebrity. “Its etymology has evolved from ‘transvestite’ to ‘transsexual’ and ‘transgender’”.

The third sort of tranny/trannie turns up on Day 196: for the 1976 “Hondamatic” (automatic) transmission. Gardiner adds to the gender and diction confusion with the use of the old Samuel Johnson quote about a woman preaching”[It] is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well, but you are surprised it is done at all”. The use of the misogynistic quote is not a surprise from someone who titles a list of women motorcyclists Sisters have always been doin’ it for themselves.

Gardiner finally gets around to the transsexual/transgender tranny/trannie on Day 285, which is ostensibly dedicated to the winners of the Dopey-stunt award for the worst or dumbest motorcycle stunt in a given film. One of the recipients is Matrix Reloaded (2003), which is a sensible choice given Gardiner’s explicit and implicit criteria. Gardiner quite properly credits the film (however dopey he finds the motorcycle stunts) to the Wachowski Brothers. Gardiner couldn’t resist adding that they are brothers no longer since one had a “sex-change”. He does resist adding that since the operation, they are known as The Wachowskis. Some writers and reviewers “backdate” that credit to avoid confusion.

Gardiner makes no attempt to avoid confusion on Day 357, a checklist for putting a bike into storage. Point 10 is to throw a tarp or sheet over the bike for protection. The sub-head reads: “Cover it up like a Republican congressman caught with a trannie hooker”. While it is clear enough that Gardiner doesn’t mean transmission, whether he means transsexual or a transvestite is an open question.

Gardiner clearly has drag and gay sex on the brain, even if he does miss out on Lawrence. A quick glance at Gardiner’s blog confirmed it. His 15 May 2013 post used David Emmett’s question at the April MotoGP press conference as a point of departure to discuss whether Rossi is gay. You know: the same Rossi who has yet to race the TT. Gardiner refers to Rossi as the elephant in the room.

Rossi was not the elephant in the room. The elephant in the room was and is an exclusionary subculture that bullies anyone that doesn’t fit the champion model of the white straight male Christian. By using such words as trannie for derisive comedy, Gardiner is reinforcing the dictates of the subculture. In other words, if Gardiner really feels it’s OK to be gay, then a subculture where it’s not OK to be gay is in itself not OK.

The full depth and range of sexism, homophobia, and racial and religious intolerance in the paddock is well beyond the scope of both Bathroom Trivia and this column. As for the book itself: it’s an example of a bad book happening to a good writer. One’s time and money might be better spent on Gardiner’s excellent Riding Man, the only book on the TT I ever thought was a keeper

The Art of BMW: 90 Years of Motorcycle Excellence (2013) is one of the better books of its kind. It combines the marque book – a volume dedicated to a specific marque or model – with the coffee table book – a volume dedicated to quality photography of a particular subject. These types of books are all but critic proof. But just as if someone creates a foolproof plan, someone else will come along and create a better fool, The Rider’s Digest has a better critic.

Books dedicated to a specific marque have a built-in readership. Such books cater to the geeks of the riding world. People convinced that the Norton Commando, say, is one of the finest motorcycles ever built will happily buy anything and everything related or dedicated to the Commando (perhaps even I Bought a Vampire Motorcycle). People who can take their Commandos or leave them might have that one ‘good’ book on the subject just for reference. (It would have made life measurably easier if I had that one good book on the Velocette.) In short, The Art of BMW is for Beemers who can’t get enough of their favorite marque.

But there is more to the book than that. Or rather less. Like all coffee table books, there is exquisite upmarket high street photography of motorcycles with only enough text to connect the pictures. Such volumes cram the shelves of used-book stores large enough to have a dedicated transportation section. The one near me in New York always seems to have about six running feet of picture books dedicated to Harley Davidson, in part because The Motor Company all but has its own publishing arm – there are even Harley Davidson branded paperback thrillers – and in part because I buy most of the books about other marques for my personal motorcycle reference shelf.

That shelf – which has now taken over a few bookcases – includes seven (used) books about BMWs: BMW by Don Morley and Mick Woollet (1992); Illustrated BMW Motorcycle Buyer’s Guide by Stefan Knittel and Roland Slabon (1996); The BMW Story by Ian Fallon (2003); BMW Motorcycles by the late and much-missed Kevin Ash (2006); BMW GS Adventure Motorcycles by Hans-Jurgen Schneider and Dr Axel Koenigsbeck (2009); and BMW Motorcycles by Holmstrom and Brian J. Nelson (2009). The seventh book is the earlier edition of The Art of BMW, subtitled 85 Years of Motorcycle Excellence.

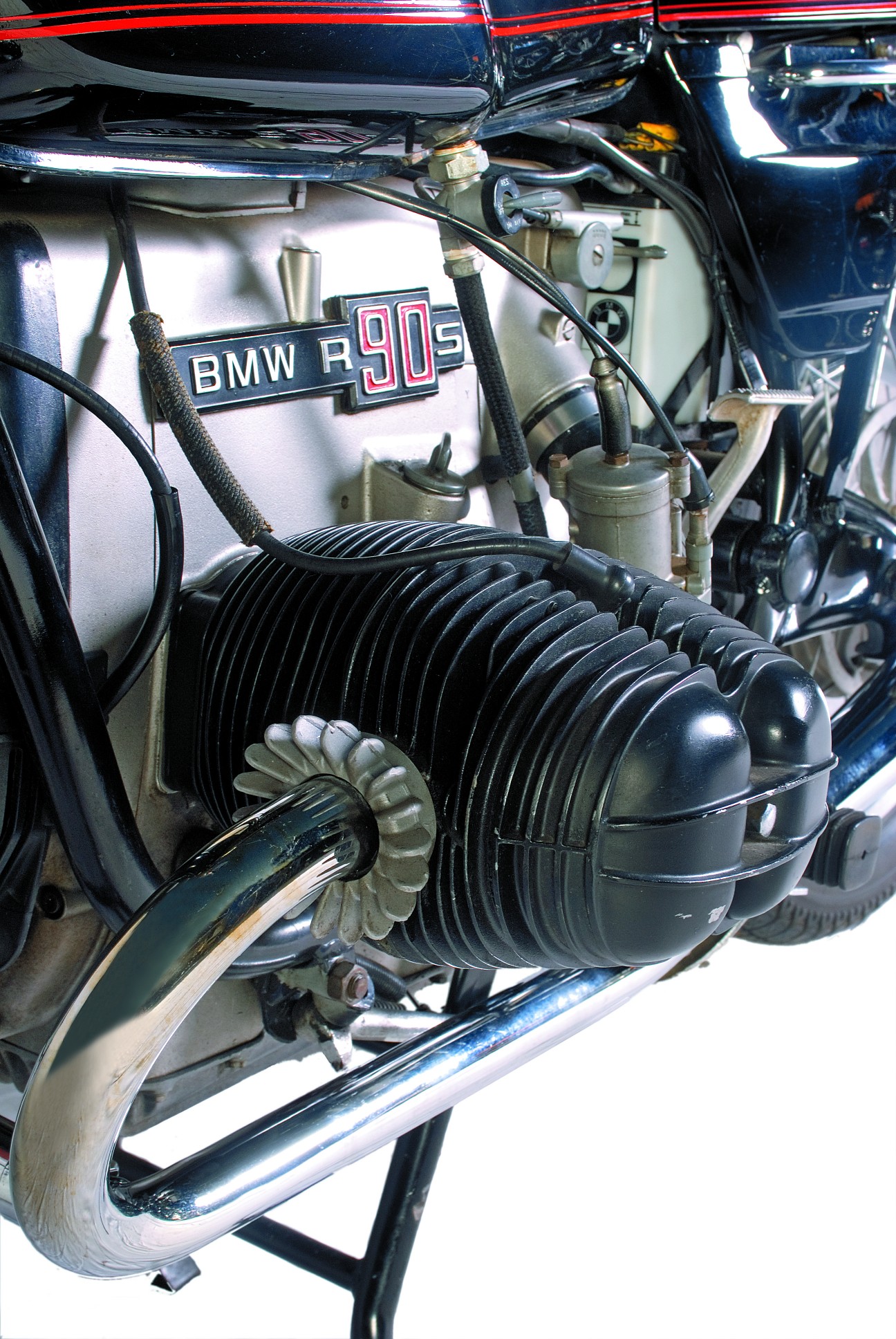

The revisions, if any, will be noted as we go along. Let’s start with the strengths, which are the photographs. The pictures are glorious. Taken by Henry von Wartenberg, each motorcycle gets a one to seven page photo spread, typically in the three to five page range. The motorcycles covered range from the 1925 R32 to the 2012 F800GS. The earlier, older bikes are drawn from Peter Nettesheim, a well-known collector of vintage BMWs, while the later, more recent bikes seem to reprise the 2007 and 2012 product lines.

The motorcycles are presented as objects in space, seen against a neutral white background, without props or scenery to distract from the images. The images are sharp, popping not just details, but also textures: of headlamps and handlebars; saddles and speedos; tool kits and wheel spokes. The more traditional motorcycle shots – top, back, side, front – are lush and vivid as well.

While most of the motorcycles look to be in pristine condition, one, a 1941 R12, is in its original condition, unrestored and unrepentant, aging, and proud of it. My favorites were the R51/2 (1950), the R69S (1965), and the R 60/2 (1967). A friend got a kick out of the 1969 “Polizei” bike. It’s pure motorcycle porn.

The actual text is uneven, ultimately falling short, which is not unexpected in a coffee table book. The sections of the text that present either the development of BMW’s motorcycle technology or the specs of specific models are the best. Functioning as captions, such sections should delight the marque geek as much as the photography. (I can’t speak to the accuracy of the specs; all buying and reading motorcycles books makes me is an expert in buying and reading motorcycle books, and not the subtleties of German engineering.)

The rest of the text by Peter Gantriis (and edited by Holmstrom, who likely did more than the usual heavy lifting here) is less compelling. It frames the photographs with carefully phrased context for each bike, its history as well as its place in BMW’s history as needed. Nettesheim, the collector highlighted by Fred Jakobs in his oddly written forward, fades from the text, leaving a trail of unanswered questions behind. What drove him to collect BMWs? What are his tales of acquisition? Most collectors have a handful of sure-fire dinner-party stories about their collecting and their collections. One or two of those might have made for livelier reading.

The primary difference between the previous edition and this one is the 2012 product line. The cover picture is different. There have been some line edits and changes, mostly substituting 90 for 85. The old flyleaf read: “Over the next 85 years the company would create the most innovative and technologically advanced motorcycles produced anywhere on earth”. The new flyleaf reads: “In the 90 years that have followed, the company has created the most innovative and technologically advanced motorcycles produced anywhere on earth”. That edit falls somewhere between a difference without a distinction and fixing what ain’t broke. Only the number of years needed to be changed.

The writing dares to be dull. Gantriis is careful not to offend. World Wars are just unfortunate circumstances that just happened. “Of course, in the late 1930s, geopolitical developments were overshadowing the world of motorcycling, and reliable vehicle and engine manufacturer, BMW, would again be pulled into war production.” A few pages later he picks up that thread in a section with the subhead “World War II”: “Production of civilian motorcycles came to a halt in 1940. Germany was by now fully engaged in conflict, and the nation’s industrial power was redirected to support the military effort”.

Of course, in the early 1930s, the geopolitical developments that were overshadowing the world, not just motorcycling, was largely German in origin, not that Stalin, Franco, and Mussolini were just bit players. Oh, and the H-name? It’s never mentioned. Nor is the party he led.

Now no one reads the history of any German marque for insights into World War II in general or the Third Reich in particular. That’s what mainstream and military history books are for. There are books about military motorcycles that also delve into such economic and political relationships. Nor would it be an appropriate venue to discuss war atrocities and reparations. For the moment, that’s better carried in the newspapers. There was a flurry in the British press about that about a year, year and a half ago.

People read books about marques for reliable information about the marque they can’t get from more general sources. If a book has fudged a fact that big, the careful reader might wonder what other facts have been fudged.

Fortunately for BMW and Beemers everywhere the truth of a motorcycle is in the ride. And here in the pictures. And no one buys coffee table books for the text. If BMW is not also selling prints, it should be.

Jonathan Boorstein

To see further spectacular images, click on the “The Art of BMW photos” link

I would not even understand how I finished way up in this article, on the other hand idea this specific post once was great. I can’t acknowledge exactly who that you are on the other hand certainly you will a well-known writer for those who aren’t by now. Best wishes!