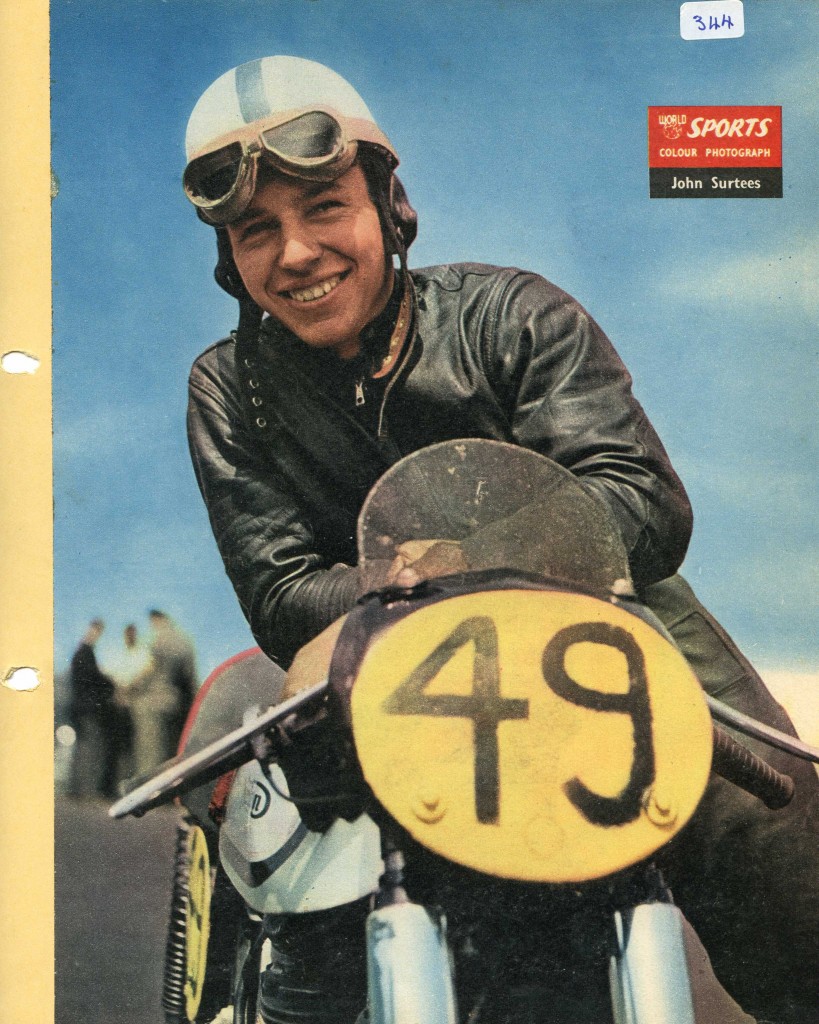

Riders’ Lives Special ~ John Surtees

When you get a group of motorcyclists together discussing racing heroes, the same names tend to crop up, all richly deserving of the accolades that follow: Geoff Duke, Mike Hailwood, Giacomo Agostini, Valentino Rossi – all with a considerable sporting heritage on two wheels and rightly lauded for their achievements.

But when the name John Surtees is mentioned, the fact that there has only ever been one man who became a World Champion on two wheels as well as four is usually mentioned soon after. It’s quite a show stopper.

We all know that Rossi tested Ferrari F1 cars on a number of occasions, and at one stage it looked as though he could possibly have been a contender for the championship on four wheels as well as two, but at 36 he is now too old, so it seems likely that John Surtees’s unique achievement will stand for many years to come.

Born in Tatsfield, close to the Kent/Surrey border in early 1934, John Surtees MBE, OBE was the eldest of three children, became the captain of his school football team, was a competitive cross country runner and was also quite handy in the boxing ring too.

His father John senior (known as Jack) owned a motorcycle shop in Shirley, near Croydon, later moving to Forest Hill, where Surtees junior’s long involvement with motorcycles first began. John will tell us more in due course about his first bikes, but as potted biographies go, young Surtees clearly had a real talent for getting round a track quickly, and in his second season of road racing, he won five of the sixteen races he entered, with podiums in a further seven.

John’s form was clearly consistent, as he went on to become 350cc World Champion in 1958, 1959 and 1960, as well as taking the 500cc World Championship in 1956, 1958, 1959 and 1960.

In 1958 Formula 1 World Champion Mike Hawthorn suggested John try his hand at racing cars on the premise that: ‘they stand up better’. Surtees did this in 1960, slotting in with his motorcycle commitments, putting it on pole and coming second in his first race in a Formula Junior and then finishing second in the British Grand Prix in a Lotus. By 1964 John would take the Formula 1 World title, driving for Ferrari.

Quite a career. To do it any justice with just a brief description I could easily fill this whole edition of The Rider’s Digest, and then some. You can read about John’s life in more depth in his recent autobiography, ‘John Surtees: My Incredible Life on Two & Four Wheels’ co-written by Mike Nicks and featuring forewords by Valentino Rossi and Sebastian Vettel. Royalties from the book will go to the Henry Surtees Foundation. I’ve ordered mine [the link is at the end of this article – Ed].

But back to the matter in hand, Rider’s Lives. TRD Editor Stuart Jewkes suggested that I might like to interview John following my interview with ‘Hairy Biker’ Dave Myers in our Winter 2014 issue, so with the kind help of John’s PA Sharon Bowness I found myself taking a ride on a sunny March afternoon to John’s beautiful 15th century manor house near Edenbridge to meet him in person.

On arrival, John showed me to his barn, where he keeps his wonderful collection of motorcycles, racing cars, and a vintage Ferguson TE 20 tractor which is awaiting restoration.

About the tractor, John said: “I was an apprentice at Ferguson, I was doing my apprenticeship at Vincent and they started having money problems, so I was transferred to the Ferguson factory.”

TRD/Martin: I’d say that little grey Fergie was in good hands. After taking a few photos of John with a couple of his bikes, we repaired to the lounge, where beside a huge inglenook we sipped Earl Grey tea and talked bikes. I started off by asking John what had made him so fast, he was clearly quite a lot faster than the others, and he’d experienced good results almost from the start, I wondered what his secret was…

John Surtees: “I first started riding after my father came home one day with some tea chests full of bike parts and said: “put it together and you can ride it”. I had a little shed at the bottom of the garden where I used to fiddle around with carpentry and trying to make model aircraft, as well as putting suspension on to my bicycle. The boxes contained a Wallace – Blackburne speedway bike, single speed, from about 1932.

“So I did that, and then he got a deal, he got a B14 Excelsior which was basically a TT bike, but they were used largely on grass tracks. And he’d started with one with a sidecar. So I got that, and I rode it over the back of our house quite a bit, and I rode it on the cinder path on the old Brands Hatch circuit, with its grass track of course, and Dad said, how about your first race? So I went off to Eaton Bray just outside Luton. It rained like hell, and I fell off every way you can imagine. And my father afterwards turned round and said “lad, I think it’s a bit big for you.”

“I used to work for him in the evenings after school, to earn pocket money and bits and pieces, and we went into Harold Daniell’s shop – the TT rider – who was just up the road from where my father had his shop in Forest Hill.

“There was a 250 Triumph there, and I thought ‘there’s lots of 250 Triumphs been made into nice racing bikes.’ It was £34, but Harold said I could have it for a special price, about £11. It was a lot of money, but I managed to get it on the basis of working it off. So I started drilling lots of holes in it, I bored out the ports, and I turned it into a racer. So basically I was a mechanic who then went along and rode it to test it. I liked my riding, but I loved working on them.

“I joined Vincent’s as an apprentice; the Triumph threw a conrod at Abbey curve at Silverstone – I was flat out – and it dumped me on the road. I thought about putting a JAP engine into it to be able to use it, but when I went to Vincent’s another possibility came up.

“There was a Grey Flash prototype there, which had been loaned to Kings of Oxford, which was Stan Hailwood, the father of Mike – he ran the business. And it had been there, done evaluation tests and come back. It wasn’t in proper Grey Flash colours or anything, but it was a Grey Flash specification bike. My father was a main distributor for Vincent, and he was taking to Mr Vincent, and he said “perhaps the lad might like to have a go at that.” So what better a rider for a Vincent than if you’re working for Vincent?

“We managed to get a deal, Dad managed to put it on hire purchase, and I got that. I put it together, and I went to Brands Hatch and the big end went. Vincent then said “try one of our experimental big ends” – so a rather famous name from the world of preparing things, Denis Minett – who was a pre-war Brooklands man – he worked there, and he built up these new flywheels, and the engine again, with this plain bearing crank pin in it. They’d tried it on a number of occasions before and it had always failed. But with my one they gave it more clearance.

“I went to Aberdare Park, and that’s where ‘John Surtees racing rider’ was born. That day I came together with the bike, it talked to me, I talked to it, and we were as one. It all came together, and from then onwards I never looked back.”

A few years later, with the MV Agusta – the bike you rode – it had quite a fearsome reputation didn’t it?

“I wanted to go to Gilera, where Geoff Duke was. I thought – ‘he’s sitting on the best bike, what better than to go there! [smiling] You’ve got a World Champion, so what better than to go there.’ But that wasn’t possible.

“The other thing I wanted to do, before that, was to stay with Norton, and to actually go back into the World Championship again, with Norton. With Nortons (sic) giving me the machines like I’d ridden at the end of the year, but with a bit more development, and also the works mechanics – the Edwards brothers.

“And by chance we’d come across some support to do it, and it was The News of the World! They were willing to sponsor this thing in the early days – a British entry back in the World Championship.

“But Gilbert Smith – the Norton MD – turned it down, on the basis that if I was successful, I would earn more money – it was still a trifling sum – more money than a director of the company!

“A man called Bill Webster [British MV Agusta agent] said: “The Count wants to talk to you”…

“So I put it off a bit, and then I said OK, I’ll go over there. I went over there, and first of all I said I wanted to try the bike.

“I went to Monza, I only did two or three laps, because the circuit was in too bad a condition. All the autumn leaves had fallen on the Lesmo corner, so you couldn’t really ride properly.

“So the only alternative was to go to Modena. It was the first time I’d seen the test track at Modena, which is where Maserati and Ferrari and everybody else tested. So we went there, and there were no leaves there, but what did happen was it rained hard. They wanted to cancel the test, but I said no, someday we will have a wet race, let’s try it.

“I thought the whole thing was too soft, and needed to be tightened up as a bike to get a better feel, but I loved the sound [smiling] and I thought ‘well, why not have a go?’ So I agreed to go along and join them.”

So they gave you the freedom to change the suspension setup and everything like that?

“To a certain degree. Luckily you had Arturo Magni there, and I first of all immediately got involved with doing what we’d done before, and working with the damper people to get things in. I also said I wanted freedom as to what tyres I used, so I was able to test with Dunlop and Avon, so that was good.

“Making any major changes was always difficult. We took longer than we should have done. Count Domenico Agusta was always very involved with the helicopter business on the other side of Agusta, and unless you saw him no-one would do anything!”

So he had to ‘rubber stamp’ everything?

“He had to rubber stamp everything! Slowly we got bits and pieces changed, and we got the bike a ‘bit’ more rideable for ’56. And ’57 was a disaster, because they decided to change the bore and stroke a little, and of course in ’57 you had to use streamlining, but our streamlining didn’t work. Whenever we had the streamlining on the engine failed.”

Overheating?

“It always had hot spots and things like this, it was partly that the modifications they’d done were a bit marginal, and secondly it just wasn’t breathing properly. And that was sad, because the only Grand Prix I was able to win that year was the Dutch Grand Prix where I ran without streamlining but it was hard work. You couldn’t afford to give away 12mph.

“But the important thing was, at least by the time we got to 1960 with the bike we’d tightened it up, we’d made a new frame, I’d managed to get permission to do that, and changed the forks and a few things, and tidy it up, we were restricted by the size of the engine, which always was a big engine. I wanted them to make a small one, but that never happened until they made the small ones in the 70s.

“The first time I rode one of the small ones was when they persuaded me to come back to to do the historic TT laps in 1979. Corrado Agusta sent over one of the Phil Read/Agostini four cylinders. I then had that, I went to a number of places, I rode it in Italy and Germany and everything, it was a lovely bike.”

Did you find it much different to the previous model?

“It was all we’d dreamed about trying to create in the earlier years . It was a really nice bike, I would have loved to have actually kept it. I had great fun on that.”

How did you manage to build up your collection, if you don’t mind me asking?

“I continued working with Nortons and everything else, even during the period that I was racing for MV. I built bikes, I built the Arter AJS during that period, and one of the Nortons that Mike Hailwood rode came from me, one I’d built, so I had an enormous amount of parts which were laying around. At that time bikes were in production, so second-hand parts and works stuff didn’t have that much value, I was going to sell them to my old team mate, John Hartle, but he got killed, and so the stuff just stayed in boxes.

“Vincents – I had parts of a works Grey Flash, and parts of my original one still, and some of the original Norton stuff. Then what happened was that when I had to stop my car racing team because of a failure of a sponsor. I was so upset that I turned my back on cars and went back to bikes.

“That’s when I went along and I found the 1939 TT-winning Georg Meier RS 255 Kompressor BMW and restored it and I started riding that, and I borrowed some Benellis, which again were great bikes, and the MV and things like that, and I went around all the old contacts I had, scavenging parts. And that’s how I found the parts for the bike I should have ridden in ’55, which was the F Norton, the horizontal one; the one with the engine lying flat, like a Moto Guzzi. I’d always been intrigued by what had been said about it. When I visited Syd Mullarney, who had made a name for himself with modifications to Nortons, I saw the parts laying under the bench. Parts he had bought with a lot of others when Nortons in Birmingham closed.

“So I was able to get a lot of stuff from him to put some of the bikes together, which might have been some of the parts from my original bikes, I don’t know! But at least they were genuine parts and what helped me was that Charlie Edwards, the original Chief Mechanic of Nortons who had built and ridden the original F, came aboard to help me with the getting the specification right.

“So that’s how I built up the collection. I haven’t been able to keep everything, I’ve had to sell some stuff because of other commitments, but I’ve tried to keep a core of things which have got an association with my past, which I have gained pleasure from and which now I try and make work to assist fundraising with the Henry Surtees Foundation.”

John had earlier told me that BMW had asked to have his Georg Meier BMW Kompressor in their museum because they didn’t have one. He is apparently welcome to go over there and borrow it at any time.

I then asked John whether, having been a Formula 1 World Champion, he considered himself a motorcyclist first and then a car driver, or vice-versa.

“My first passion and love in life was motorcycles.”

And still is?

“I don’t go along and say that the cars are just a sideline, I was deeply involved in cars as well. It was only the situation that happened at Agusta that changed me. The Count had got very upset because the Italian newspapers had said ‘Surtees doesn’t need an MV to win.’ Because I’d been riding some of my own bikes I’d won here on the British circuits, and he said ‘No no! No more! Only ride MV Agusta, and only Championship races.” I was racing in ’55 for Nortons, my NSU and my own bikes as well, I did 76 races in the year.

“I was going to go down to about 16, and I loved my racing, and that wasn’t on, so that’s why I thought: I’d tried a car – there’s nothing in my contract – I’m not going to break my contact, I’ll drive a car as well!

“If time had been slightly different, and for instance something like the Honda had come; that was the sort of challenge I would have liked; it might have been different. I rode that in latter years, both in England and in Japan, testing Mike’s 500 Honda, but no, I led a double life – motorcycles and cars. I had lots of friends, good experiences in bikes and likewise in cars.

“I got my bike career better than my car career, because in my bike career I served an apprenticeship. In my car career I dropped in at the top end, and I made quite a lot of mistakes – off the track. Not on it, but off the track. Relative to people. And some decisions, which probably stopped me having more success.”

But you didn’t do too badly though.

“Not too badly!” [laughing]

With that, and more than half an hour chatting ‘off script’ I thought I’d better ask John the ‘Rider’s Lives’ questions…

I think we’ve probably already covered this one, the ‘1. What was your first motorcycling experience’ question, so the second question is probably a moot point as well ‘2. What is your current bike’ and as we already discussed you’ve got quite a collection!

“I haven’t got a current road bike, but if I want to I can go along and jump on a Comet, a Black Shadow or a BMW R68.”

You could put them on the road and ride them?

“They’re all up and running.”

3. What bike would you most like to ride or own?

[Long pause]

“That’s a difficult one.”

[Another long pause. John receives a text message on his iPhone and reads it without needing glasses…]

“It some ways it may sound strange, but I’d probably reverse the deal I did and not sell the Georg Meier BMW Kompressor. That first love as a youngster. I’m probably just showing my age (laughing) but I’d probably like to reverse that deal and have it back.”

[From John’s website: ‘It was a picture of 1939 Isle of Man TT winner Georg Meier that really fired his imagination. Marooned on the Yorkshire moors outside Huddersfield – well away from the blitz – John used to pore over Jack’s old race programmes and copies of Motor Cycle and Motorcycling. One – featuring Meier hurtling down Bray Hill on his way to victory – really captured John’s attention. “I’ve never been one for hero worship but that picture made an enormous impression on me,” he recalls.]

“There’s lots of bikes out there which I think are fantastic, and I’d love a try, but there’s things about memories as well as you get older, and in some ways I’d like to perhaps reverse the situation and be back owning that BMW” [smiling]

4. What was your hairiest moment on a bike?

“I suppose the two hairiest moments were the two main accidents I had in my career on bikes. The first one was quite a stupid one, it was my first visit to the Isle of Man, and that was on a 125cc EMC. I’d been asked to ride it, and I’d taken the opportunity because I didn’t know the circuit, and I thought the more riding I did, the better, so I thought ‘why not?’

“So I took my two Nortons, my 350 and my 500, and when I got to the Isle of Man Joe Craig, the Norton team manager, came to me and said: ‘I want you to ride the works bikes’ – he didn’t want me to ride the EMC. I said: ‘Look, – my dad was there and he was always very involved with things,- we said we would, we promised. Unless they release us we won’t do it.’ So I went to Joe Ehrlich (EMC founder) and said ‘I’ve got this opportunity to ride the Norton works bikes’ but he said ‘no no, I’ve made agreements and arrangements.’ And so fine, I rode it.

“I got as far as Ballaugh Bridge, I went over Ballaugh Bridge, and just after that the forks broke, one of the fork legs broke, and it took me into the gutter and chucked me off, and that was the result [pointing to his left wrist] a scaphoid, which put me out.

“And that of course was a very fateful thing, because on the boat going back I wondered why, when we were listening to the radio, there was no mention of Les Graham. Of course it was when poor Les Graham got killed on the MV Agusta.

“So that was one occasion, the other was the possibility in my first year at MV, of winning the 350 Championship as well as the 500. I was in competition mainly with Bill Lomas, on a Moto Guzzi. We were at Solitude in Germany, where the German Grand Prix was. I was dicing with him, using a bit more road, and then a bit more road and then on this one occasion I used a fraction too much, and I lost the front wheel, and I ended up lying in a Stuttgart Hospital with a broken arm.

“While I was lying in that hospital, if either Geoff Duke or Walter Zeller had won the Ulster Grand Prix, I wouldn’t have won my first World Championship. Luckily they didn’t, and I did win it while I was lying in hospital in Germany with my humerus broken. I didn’t find it funny (smiling) but it was the humerus they told me!”

5. What was your most memorable ride?

“Two different things, I think the most important ride was that ride on the Vincent that I mentioned, at Aberdare Park. It was important because that’s when everything clicked, mentally, physically and everything else.

“Also probably the ’59 TT, when the weather conditions were so horrendous, that no bikes had any advantage, so that was very satisfying to come away winning in what was rain, sleet, snow and wind!” (laughing) It was satisfying because people were saying ‘oh well, he’s got a better bike’, but they didn’t take into consideration that everybody I was racing against I’d beaten on a Norton as well.

6. What would the ideal soundtrack be to this ride?

“I think music has a relationship; the way a musician has to come together with his instrument is something which in many ways is not so much different to how one comes together with a machine, and so I think there’s always a very similar thing there.

“But what goes with the ride? It depends what one thinks. I drove a lot, backwards and forwards from Italy, I’d get in my car, and something which would relate in this fashion would be listening to Greig, and the Piano Concertos; the highs and the lows, (smiling) the emotion that really fitted in with me, going over the mountain passes and things like that, so probably I’d associate that.”

7. What do you think is the best thing about motorcycling?

“Well I think one of the best things about it from a point of view of when I started, was its simplicity. Something which unfortunately I think has now disappeared, with all the technology which is put into everything. It was something where lads came up, and they’d have an older bike, and they’d tinker with it, and they’d get it going, they’d do their own servicing without having to have all this special equipment! (smiling)

“And so that was the thing. The simplicity of putting it all together, and the fact remains that also, it was riding a bike was something which you did actually get that feeling through the seat of your pants, and through your fingers and your body generally. You all became as one, and this was very special I thought. So in a way a bike would be very much a learning thing, you’d learn lots of bits and pieces with it; very convenient.

“I remember very well when I was an apprentice, I’d borrow a road test bike and nip home in order to prepare my motorcycle in the end. I’d nip from Stevenage through to Addington in Croydon. It took me about the same amount of time as it would take me now to get as far as London! [laughing]

“Of course, there was no traffic on the roads; in those days there were no speed limits outside of the built up areas, and there was an awful lot of freedom.

“But I think one of the things that people still very much appreciate – fine, all the technology is wonderful, but the reason why there’s a big following for the classics is that somehow people yearn a little for that period, for that simplicity.”

8. What do you think is the worst thing about motorcycling?

“The dangers. The worst thing is when I hear of people getting hurt. I see it. Unfortunately the conditions don’t get any better, and also of course as developments have taken place, cars have become so much more responsive. The average car handles very well, and in turn it means that one has to be that much more careful, because people can do things and catch you out. I think that is a concern, more could be done to educate people to keep an eye out for the two wheelers. That’s one of the biggest worries.”

9. Could you name an improvement you’d like to see for the next generation?

“Well we all talk about education, and it’s very important. Education gives people opportunities, and I suppose some more emphasis on training for motorcyclists, but also for others to appreciate motorcycles, because if someone hasn’t ridden a motorcycle they won’t appreciate how manoeuvrable they are, and a motorcycle can get itself into very difficult situations very quickly, and certainly with some of the performance.

“I think largely it is respect and education. It’s not getting any easier on the roads, with all the congestion and things like this, which in a way it doesn’t affect the motorcyclist quite so much! (Smiling)

“The fact is it doesn’t diminish the potential dangers and I think that most serious motorcyclists will treat their riding very seriously. The one danger with motorcycling is that because it gives you that degree of freedom that is rather special, they can be abused. It can be misused. That is something which has always been the case, it isn’t just now it’s always been the case.

“Also, they appeal very much to young people, OK we’re still motorcyclists, we’ve had a lot of water pass under the bridge with a lot of experience, but youngsters coming in with that freedom, so it’s a question of somehow seeing if you can provide them with a little better start.

Some of the training programmes, and some of the advice which is out there obviously has been helpful, but perhaps a little more could be done there.”

10. How would you like to be remembered?

“How would I like to be remembered? I think there’s many things which one could say about that, but to put it into a few words is difficult.

I think the main thing is that I’ve always considered myself fortunate to actually have got paid for doing something that I love doing. And never at any stage did I ever put money before – in fact, at times perhaps I did myself a disservice because I was excited by the challenge, and I took up something when I should have been more sensible and perhaps just chosen a car which was winning at the time, rather than one which we thought we could make winning in two years.

“But I’d like to be considered as someone who did it for the right reasons, and certainly that I’d leave no stone unturned to do that.”

What does your work with the Henry Surtees Foundation involve? I understand you’ve secured a helicopter? (This was the impression given in the BBC ‘Racing Legends’ documentary with Paul Hollywood, shown in January 2015)

“No, that’s one of the things we’ve got to try and do.

“The Foundation of course was founded purely because my son was following his heart, and went to racing. I never introduced him to racing, it was a friend who did that. But when he did, I had to do the same as my dad did, and support him.”

[John’s 19 year old son Henry was tragically killed in a freak accident during a Formula 2 race at Brands Hatch in July 2009]

“He got killed in a stupid accident, which shouldn’t have happened, but that’s the way things are.

“We have a number of programmes that we want to do, and we’re putting together at the moment, but one of the programmes – with the helicopter side – we got involved with the Air Ambulance of Kent, Surrey & Sussex, and I suppose because of the life I’ve led I’m a bit impatient.

“I like to see results from what we’re doing, and one of the things which showed up was that we had the opportunity to get involved with introducing blood transfusions into the actual point of accident or illness. So that appealed. So what we had to do is get the equipment, and then get the transport for it, to be able to ferry it backwards and forwards between the aircraft and the hospital. So of course the challenge was to raise the money with events that I’ve put on and various things, so we raised the money and we paid for that, and within the first year there were real results there relative to what had been achieved, people’s lives need to be saved.

“We just this last week gave the second part for the Great Northern helicopter service, which was the supply of two vehicles to do the ferrying, previous to that we supplied the money to buy the equipment. So that’s there and we’re talking to a few others.”

On February 25th 2015 two Vauxhall Mokka 4×4 vehicles were handed over to two charities – Northumbria Blood Bikes and Blood Bikes Cumbria – which provide vital transportation of blood in the region for the Blood on Board’ project

“The Kent, Surrey and Sussex Air Ambulance have another project which could potentially – and we’re looking at this – introduce scanners into the aircraft so that at the point of the incident a scan could be taken to ascertain what the real injuries are, and then you decide on where is the best place to take the person.

“What appeals to me is that all my life I’ve been trying to save time, I’ve been fighting time, and there is nowhere, in illness or injury that’s more important than time. So blood transfusions can save all this time, if you can do a scan, there’d be even more time. But, you start loading these helicopters up, you need more payload, you also need a bigger range etc. so the programme is to have – guess what – an Agusta helicopter.

“So as a representative of the Foundation, we haven’t got the sort of money and things to be able to fund that.

“What we want to do is see if we can fund the scanners, and the other equipment to go with it, but certainly I want to use whatever influence I have with people and contacts I know to help them buy the helicopter. And that’s what we’re trying to do at this moment.”

John Surtees is a truly remarkable man. So many great achievements, but so down to earth. An inspiration to riders and drivers, young and old, and having to deal with a devastating personal tragedy that no parent should have to suffer, he is using his energy and influence to help save the lives of others.

Please visit the Henry Surtees Foundation website and support a good cause in any way you can.

Martin Haskell

John Surtees’s biography is available here.