Longing and Belonging: Toward a Cultural History of Gay Motorcycle Clubs in the US

The Satyrs Motorcycle Club is the oldest gay continuous motorcycle club in the United States. Established in 1954 in Los Angeles and still going strong, they have become one of the best known gay MCs in the country.

When we look at such an MC, we are looking at more than just the history of the time and the club. We are also looking at such themes and issues as camp, bricolage, and identity politics on the one hand, and questions of sexual orientation, real or imagined, overt or covert, latent or manifest, on the other. We are looking at how the nexus of two identities – gay and motorcyclist – self-imposed as well as imposed by society at large, plays out in public and private.

While there have been gay and lesbian motorcyclists almost as long as there have been motorcycles, things don’t get interesting until World War Two ends. Perhaps too interesting. The first images in popular culture of the gay motorcyclist seem to be intertwined with postwar and Cold War politics, often reflecting and coopting the images of mainstream motorcyclists in the process.

The tale of motorcycling once the war ended is known well enough. Between the manufacturers and military surplus, motorcycles were sold as cheap transport and recreation to mostly working class men who were not always ready, willing, or able to buy or buy into the American suburban dream. Against the backdrop of the trials of key members of the Axis powers for various war crimes, the bikers banded together with a mix of working class resentment and disillusionment combined pre-war Nazi sympathies and prejudices. By the time the main events of the Nuremburg trails had ended, the Cold War had heated up intensifying an us-or-them tribalism in general and racism in particular.

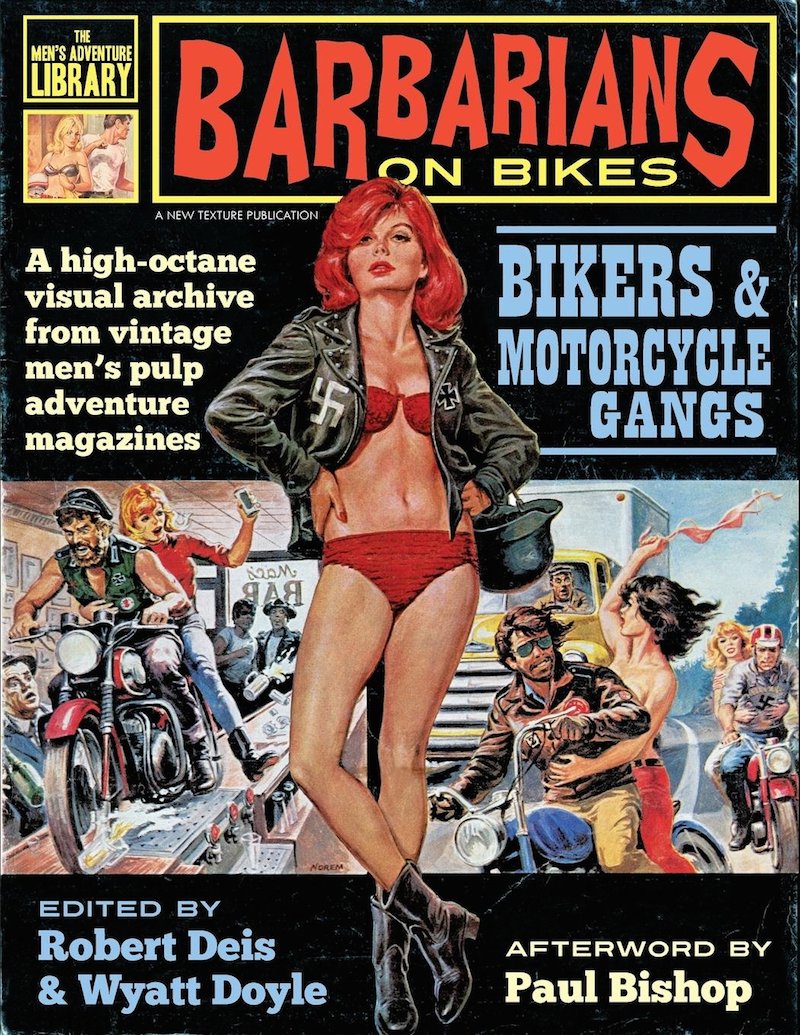

It can be argued that it was attitude as much as alcohol that lead to the much hyped Hollister Riots in 1947, which appalled a nation eager to get back to an illusion of what normal life was before the war (and perhaps they even enjoyed being appalled). Little wonder two of the most popular villains in pulp fiction of the era became Nazis and biker gangs, according to Bob Deis and Wyatt Doyle in Barbarians on Bikes: Bikers and Motorcycle Gangs in Men’s Pulp Adventure Magazines. The use of Nazi regalia by some gangs probably helped.

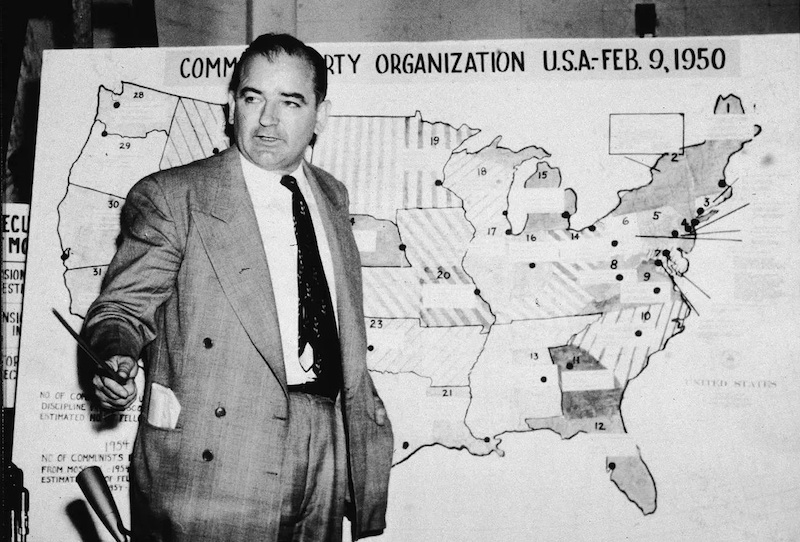

But Hollister and the Cold War were not the only notable events undermining or underscoring the would-be status quo. 1947 also saw the birth the rightwing McCarthy hearings. The investigation supposedly was to address communist influence and infiltration, but quickly developed a homophobic and anti-Semitic edge. By the time the second wave of the hearings were in full swing, the Red Scare had become the Red and Lavender Scare. Homosexuals were seen as either communists or security risks, if not both, which lead to mass firings of homosexuals from government agencies. By linking communism with homosexuality, the hearings created a sense of guilt through association, especially when any real evidence was lacking, as was so often the case.

Incidentally, the witch hunt was racist as well, regarding any attempts by people of color to obtain equal rights as the results of outside agitators (i.e. communist). The assumption was that without such “agitators”, the visible (race or gender) and invisible (religion or sexual orientation) minorities would know and stay in “their place”.

By the time the first half of the 20th Century was drawing to a close, both gays and motorcyclists had identities as outlaws, threats to the American Way of Life, imposed by the mainstream. And continuing the concept of guilt by association, many saw the aggressively masculine behavior of the motorcycle clubs and gangs as examples of overcompensation by men who really weren’t masculine, that is, were gay, or latent homosexuals. This attack was particularly popular in the left, which often found the affected masculinity of fascists questionable.

Neither Orpheus (1950) nor The Wild One (1953) did much to challenge those perceptions. The eerie and erotic pale riders in Orpheus with their leather gauntlets and Indian motorcycles are elegant assassins. The Wild One not only is an iconic film, but also has an iconic performance by Marlon Brando, which is parodied and paid homage to, to this day. The bikers here are rebelling against the American Dream and Way of Life. David Thomson in his obituary of Brando for The Guardian claims “the biker…[is] a very camp figure, a gay icon”. Others commented that the bikers in the film were just latently homosexual.

Which brings us back to the Satyrs and the founding of their motorcycle club in 1954. Because of the Lavender Scare witch hunt, most homosexual organizations followed the cell structure format established by Harry Hay for the Mattachine Society, an early lesbian and gay rights group. (Hay, an actual communist, was ultimately expelled from the Society he founded.) Instead, the Satyrs created something closer to what the American Motorcycle Association (AMA) would approve. The bylaws become the template for most gay motorcycles clubs of the period. If Larry Townsend is understood correctly in a passage about gay motorcycle clubs in The Leatherman’s Handbook, due to period attitudes toward homosexuality, many of the gay motorcycles clubs became disenchanted with the AMA and broke formal ties while following the organization’s lead in questions of safety and the like.

Which brings us back to the Satyrs and the founding of their motorcycle club in 1954. Because of the Lavender Scare witch hunt, most homosexual organizations followed the cell structure format established by Harry Hay for the Mattachine Society, an early lesbian and gay rights group. (Hay, an actual communist, was ultimately expelled from the Society he founded.) Instead, the Satyrs created something closer to what the American Motorcycle Association (AMA) would approve. The bylaws become the template for most gay motorcycles clubs of the period. If Larry Townsend is understood correctly in a passage about gay motorcycle clubs in The Leatherman’s Handbook, due to period attitudes toward homosexuality, many of the gay motorcycles clubs became disenchanted with the AMA and broke formal ties while following the organization’s lead in questions of safety and the like.

While the two outlaw identities were becoming increasingly intertwined, a third development grew in importance: what Jack Fritscher would later dub “homomasculinity”, which the web-based Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia defines as a “subculture of gay men who prefer masculine-identified men”, or men who prefer men who look and act like men, sometimes exaggerated, vaguely working class, who were often seen as more authentically male than men form other socio-economic classes. The archetype – or stereotype – of the effeminate, if not exquisite, vaguely upper class, always piss-elegant, male finally had some serious competition.

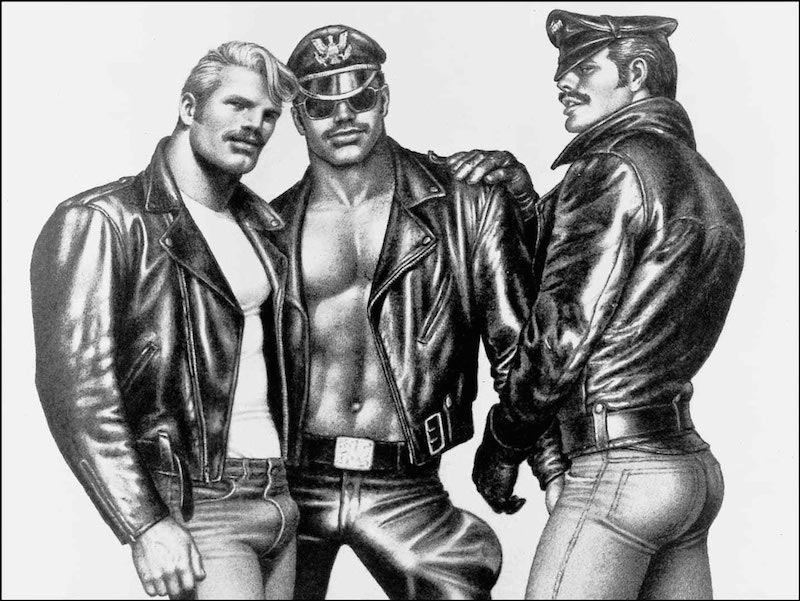

Homomasculinity was the real focus of the 1950s physical culture magazine, providing just modest images of well-muscled men with such masculine props as cowboy hats, Roman swords, engineer boots, and the like. In 1957, Bob Mizer, the publisher and main photographer of Physique Pictorial, one such magazine, added drawings by Touko Laaksonen, an artist who would soon be known as Tom of Finland.

Laaksonen’s day job was in advertising, which had as much an influence on his art as his sexual interests. His homoerotic images of hyperstylized homomasculinity were as facile as they were commercial: he was very much the right artist at the right time. However, there was more to the fetish imagery of laborers, motorcyclists, and military men than mild sadomasochism. Because he was influenced by both leather-clad bikers and soldiers from the German Wehrmacht (who were in Finland when he was growing up during the Second World War), his images often crossed the fetishistic with the fascistic.

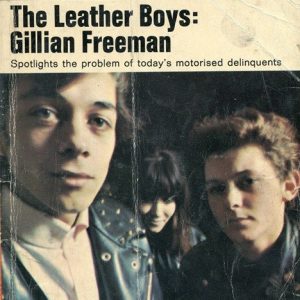

Four years later, there were two notable events: one of the last of the big war crimes trials (Eichman) and the publication of The Leather Boys. The trial emphasized yet again that individuals were responsible for war crimes; while the novel introduced gay motorcyclists to the world at large. (That the Rockers included gay and lesbian riders would not have been news to either group.) The working-class gay lovers, Dick and Reggie, want each other to be as they are and not pretend to be women, hitting that homomasculinity note softly. Interestingly, The Washington Post chose to highlight that in its obit of Freeman with this quote: “‘When you kiss me…you don’t pretend I’m a girl or anything?” Dick asks his new lover. “Don’t be daft,” Reggie says. “’ow could I pretend you was a girl? You’re the wrong shape…I don’t want to pretend you’re a girl, neither’”.

Four years later, there were two notable events: one of the last of the big war crimes trials (Eichman) and the publication of The Leather Boys. The trial emphasized yet again that individuals were responsible for war crimes; while the novel introduced gay motorcyclists to the world at large. (That the Rockers included gay and lesbian riders would not have been news to either group.) The working-class gay lovers, Dick and Reggie, want each other to be as they are and not pretend to be women, hitting that homomasculinity note softly. Interestingly, The Washington Post chose to highlight that in its obit of Freeman with this quote: “‘When you kiss me…you don’t pretend I’m a girl or anything?” Dick asks his new lover. “Don’t be daft,” Reggie says. “’ow could I pretend you was a girl? You’re the wrong shape…I don’t want to pretend you’re a girl, neither’”.

1963 saw the release of two films that are unlikely to ever be part of the same double bill: Beach Party and Scorpio Rising. Beach Party, a piece of fluff aimed at the teenage market, included a character named Eric von Zipper, who was played by Harvey Lembeck as a sly, camp send up of Brando in The Wild One. The bungling biker was popular enough to be brought back in five of the sequels. Scorpio Rising is a more serious art film by the auteur Kenneth Anger. R.L. Cagle, in his monograph about Scorpio Rising, notes, “a shift in the male characters’ desires from motorcycles, to one-on-one encounters, to sadistic orgy, and ultimately, to a new kind of fascism”. The Hells Angels weren’t amused to be thought homosexual because of the film; the American Nazi Party threatened to sue Anger for defamation of character.

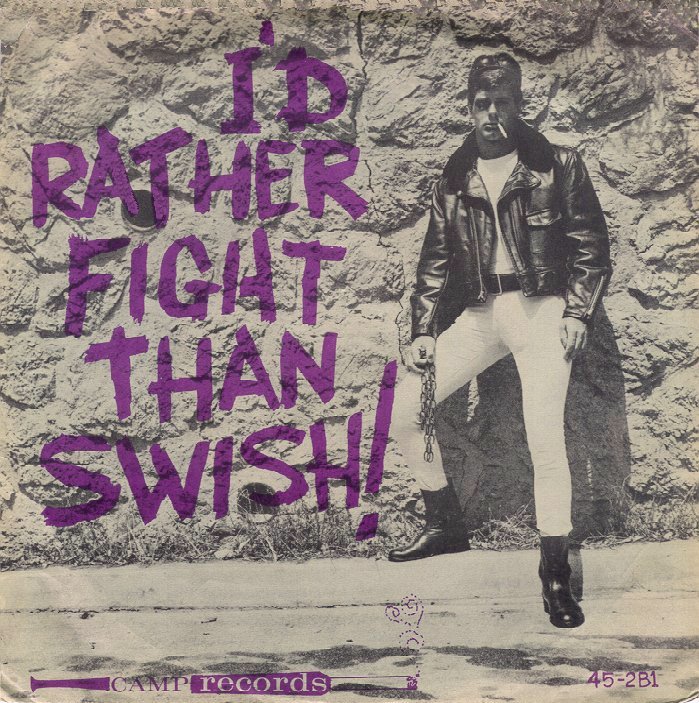

After that, the film version of The Leather Boys in 1964 would have seemed tame in comparison even if it had left the gay content intact. Instead it was toned down considerably, but nevertheless conveyed a more positive attitude toward homosexuality than was usual for the time. That same year, while the Beatles were busy invading America, a small record company in Los Angeles released a series of 45 rpm novelty songs with gay themes and comedic lyrics. Camp Records discography included such gems as “Florence of Arabia”, “Leather Jacket Lovers”, and “I’d Rather Fight Than Swish”, a bit of wordplay from the then contemporary advertising tag line, “Us Tareyton smokers would rather fight than switch”.

The advertising copy for the song itself refers to both the Beatles and motorcycles. “Admist the sounds of motorcycles, chains, and wails of YEAH, YEAH, YEAH, comes a song pertinent to today’s world! Wilder, madder, gayer than a Beatle’s hairdo!” The actual novelty number echoes less the British Invasion and more American rockabilly or rock-and-roll. The song is about an outlaw biker who wants to beat up effeminate homosexuals, but who may be in the closet himself. Whether that closet is imposed upon the biker by a society at large that rejects him because he is not heterosexual or by a gay subculture that rejected the working class as anything more than rough trade is left ambiguous.

The next year, Thomas A. Lynch, the Attorney General in California, released a report on outlaw motorcycle gangs. Among the more immediate accomplishments of the report was to launch the bikesploitation genre, which buried Beach Party films in general and poor Zipper in particular. To be fair, the Beach Party genre was probably doomed anyway in the context of the growing anti-Vietnam War protests and demonstrations, with the emphasis of resisting the state if the state is wrong, as had been indicated in many of the War Crimes trials. The anti-war movement also lead to the feminist and equal rights movements, the later originally called the Gay Liberation Front.

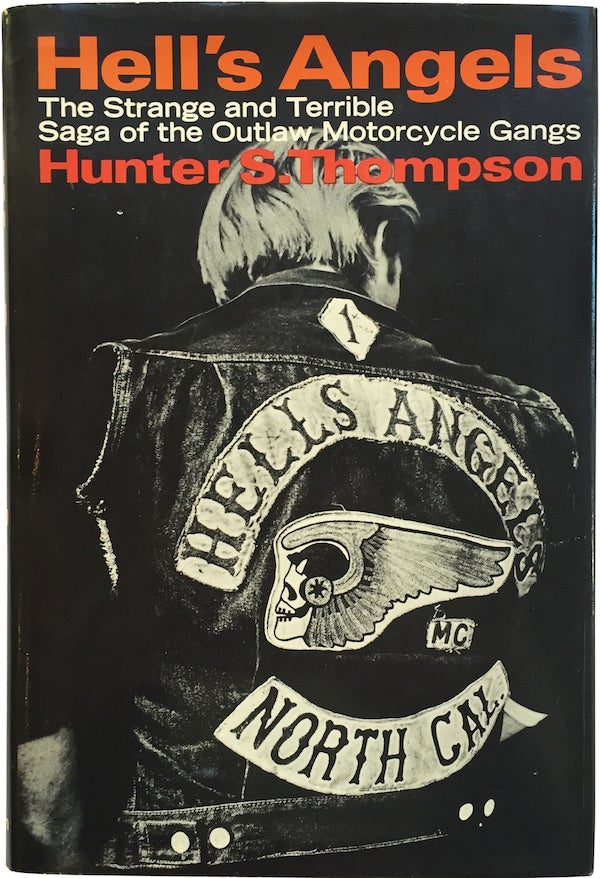

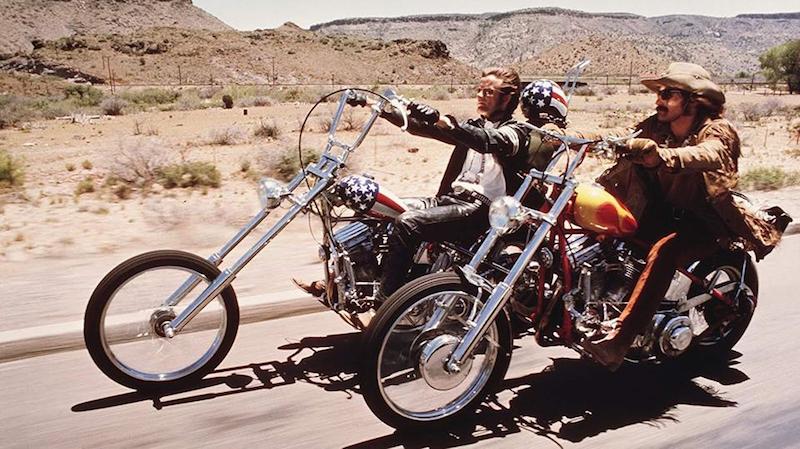

The popularity of outlaw biker gang exploitation films received quite a booster rocket when Hunter S. Thompson’s book about the Hell’s Angels was published in 1966. By the time Easy Rider was released during the summer of Stonewall, Manson, and Woodstock, the elements of the genre were well-codified, if not ossified. Oddly enough, Easy Rider itself was more a counterculture road movie than bikesploitation, even though the two protagonists were outlaws who dealt drugs.

The anti-establishment belief systems of the time prompted different approaches to dress and manners, promoting a more casual, more working class look and sound, though the real working class treated this with suspicion. It was time for homomasculinity in general and gay motorcyclists in particular to come out of the closet, if not the garage.

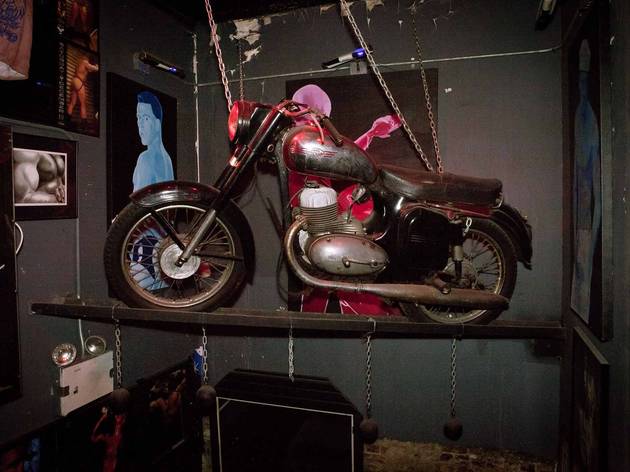

The following year, Jack Modica turned an old New York longshoreman’s pub into a leather/Levis bar called The Eagle. Decorated with not much more than several coats of black paint and an old beat-up motorcycle, the Eagle became the place where gay biker clubs held their club nights as well as other groups and individuals wanting a more masculine atmosphere than was available in the conventional gay bar of the time. (One move, two owners, and all but 50 years later, the Eagle still exists on the West Side, still decorated in black paint and still with an old motorcycle, now dangling above the stairwell, like the Bike of Damocles.)

In 1972, Townsend published The Leatherman’s Handbook, which Fritscher argues in his introduction to the Silver Jubilee edition “was a declaration of independence for ‘anatomically correct’ homomasculinity” and “as remarkable a construct as Stonewall itself” because Townsend’s “specific subject is homomasculinity” as well as that The Handbook is “targeted…to a demographic of masculine-identified men”. The target audience was also gay men interested in S/M, here called leathersex, or as Fritscher puts it, a “combination etiquette book and Boy Scout Handbook for the Mineshaft’s epic nights of beautiful people where early motorcycle-inspired leather recombinated (sic) its functional concept as riding gear to include the farthest reaches of drug-driven S&M”, involving “reciprocal concepts of power and non power. That’s why Original Recipe Leather, post WWII biker gangs, had power-structure names like “Hell’s Angels” or “Satan’s Slaves”. He concludes “leather…had become a psychologist’s dream of a symbol for an outlaw lifestyle few wanted to acknowledge”.

Townsend rode a motorcycle at some earlier point in his life and at a guess kept in close touch with riders after that. The chapter focusing solely on gay motorcyclists and gay motorcycle clubs is clearly authoritative. He points out that the gay clubs stress safety and behaving as if the club were not outlaw, which in this case usually meant not being affiliated with the AMA because of period attitudes toward homosexuals and homosexuality. He adds that is “despite the deliberate attempt on the part of some leathermen to emulate the outlaw attire” – an odd bit of drag under the circumstances. The clubs tended to be small, with rarely more than a dozen or so members. Despite the size, there was usually a full calendar of events from runs to meetings, parties to benefits. While most were in the warmer months, the winter season had carnivals or annual meetings to elect new officers. He claims that the California Motor Club was the oldest and had the most elaborate carnival. He estimates that there are between 40 and 50 gay MCs in the early 70s, and revises that estimate lower in the Silver Jubilee edition. (To judge from the holdings in such archives as ONE in Los Angeles and the Leather Archives and Museum in Chicago, there may easily may have been twice that estimate, if not more.) But even in the original edition, Townsend notices changes in the clubs: “Along with the increase in numbers, we are seeing a ‘new breed’ developing insofar as the in-group standards are concerned. In years past the clubs were beset with an almost fearful preoccupation and need to retain an unblemished masculine image. More recently this has loosened up to the point where some clubs put on social functions involving a wide variety of behavior”, with some clubs offering drag shows and one in Chicago even having a cupcake contest. He concludes, “Some of the older club members look askance, but I feel it’s a healthier situation…not to be so afraid someone will question your status as a male.”

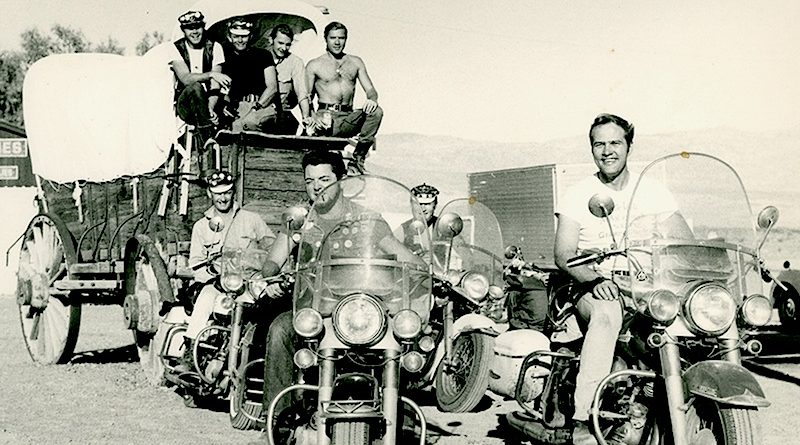

The exhibition catalogue for Band of Bikers (2010) provides a glimpse into the gay motorcycling subculture Townsend wrote about. The catalogue features photographs of three biker gatherings over the summer of 1972. The snapshots were culled from a personal photo album that the curator, Scott Zeiher, literally found in the trash. Blurry as memory itself, the photos capture a moment after Stonewall and before AIDS. The young and youngish bikers are dressed in denim and leather, colors and jockstraps, T-shirts and shirtless, smiling or grinning for the camera. The look is as much Tom of Finland as it is Eric von Zipper. The bikes and the beer cans add to the tone of carefree camaraderie. Someone sheepishly accepts an award; another poses with a helmet festooned with an anatomically accurate dildo. It’s almost the perfect mix of camp, drag, and bricolage.

Five years later, homomasculinity became a drag act and camp joke when The Village People was unleashed upon an unsuspecting universe. In addition to a biker/leatherman, there was (and still is) a cowboy, a soldier, and a construction worker, among other homomasculine types. Glenn Hughes, the biker/leatherman during the Village People’s disco heyday, actually was motorcycle mad, riding his Harley all over town and even parking it in his living room. In many ways, he was a biker/leatherman impersonating a gay male impersonating a biker/leatherman. Whether he was a member of any gay motorcycle clubs or was aware of or influenced by Lembeck, who would be Hughes’s ancestor in biker archetype send-ups, has yet to be determined. Hughes died of lung cancer and his last request was to be buried in his Village People costume.

AIDS, of course, created a rupture in the continuity of all the gay sub-cultures, and that is reflected in the history of the clubs and the bikers, even if it might not be as well documented as the sub-cultures related to such glamour industries as fashion or theatre. To be fair, the smaller clubs neglected to replace aging members with younger riders, a failure not peculiar to just the gay MCs. Some of the larger clubs began recruiting drives, including offering “scholarships” to younger riders who might like to participate in such more expensive events as runs or rallies, but might not be able to afford it.

Parenthetically, when I first heard about such scholarships around 2006, I thought back to how my nineteen-year-old self might react to an older man offering to underwrite my participation in a longer and more costly road trip. I’d take a trip, all right: about as fast and as far as my little bike could take me in the other direction. I presume the approaches are not as tone-deaf as they sound. Nevertheless, photographs of the members of still active clubs show that they are dominated by older, white riders.

Both motorcycling and homosexuality are more widely accepted now than either were 75 years ago as World War II was drawing to a close. Motorcycles now prop up advertising campaigns and burnish celebrity images. It’s no longer the sport of racers or renegades. The mainstream more or less understands that there are messengers, overlanders, dirt bikers and sports bikers as well. Nor is homosexuality seen as much as a negative as it used to be. Rather it is seen as a highly lucrative niche market made up of parents, neighbors, and coworkers, and politicians.

And yet: yet: some still feel the old battle cries and fight for the right to be an outlaw. In 2011, David M. Gross, author of the semi-autobiographical Fast Company, A Memoir of Love, Life and Motorcycles in Italy, wrote an op-ed piece for Motorcyclist, in which he hopes no one will “forget the pride we once had for the rebel in ourselves”. Noting that “any time a biker…puts on a crash helmet and lowers his visor, he starts to dream…to break out of society’s expectations of the__bourgeois__self”, he concludes, “If only more motorcycle enthusiasts today had the courage of dykes on bikes and fags on Vespas”.

And yet: yet: some still feel the old battle cries and fight for the right to be an outlaw. In 2011, David M. Gross, author of the semi-autobiographical Fast Company, A Memoir of Love, Life and Motorcycles in Italy, wrote an op-ed piece for Motorcyclist, in which he hopes no one will “forget the pride we once had for the rebel in ourselves”. Noting that “any time a biker…puts on a crash helmet and lowers his visor, he starts to dream…to break out of society’s expectations of the__bourgeois__self”, he concludes, “If only more motorcycle enthusiasts today had the courage of dykes on bikes and fags on Vespas”.

Jonathan Boorstein

Visit The Satyrs Motorcycle Club website

I truly enjoy your site. As the founding San Francisco editor-in-chief of Drummer, may I suggest for your consideration an addition to your book list? It’s my 1969 biker S&M novel, “Leather Blues,” that was serialized in Drummer and in Man2Man Quarterly. (I am also the author of “The Life and Times of Larry Townsend”; Larry was my friend and collaborator for 40 years. You may vet me at my site: http://www.DrummerArchives.com Here is a direct link for info on “Leather Blues.” https://jackfritscher.com/Novels/LthrBlues/Lthr%20Blues.html Thank you for checking this out as I, at 84, would like to support your work however I can. Cheers, Jack

Thank you. Townsend was an important figure in LGBTQIA+ history in general and human rights in particular. The original “Leatherman’s Handbook” was and remains an important source for academic papers in both queer studies and motorcycles in popular culture. — Jonathan Boorstein