Express Relief

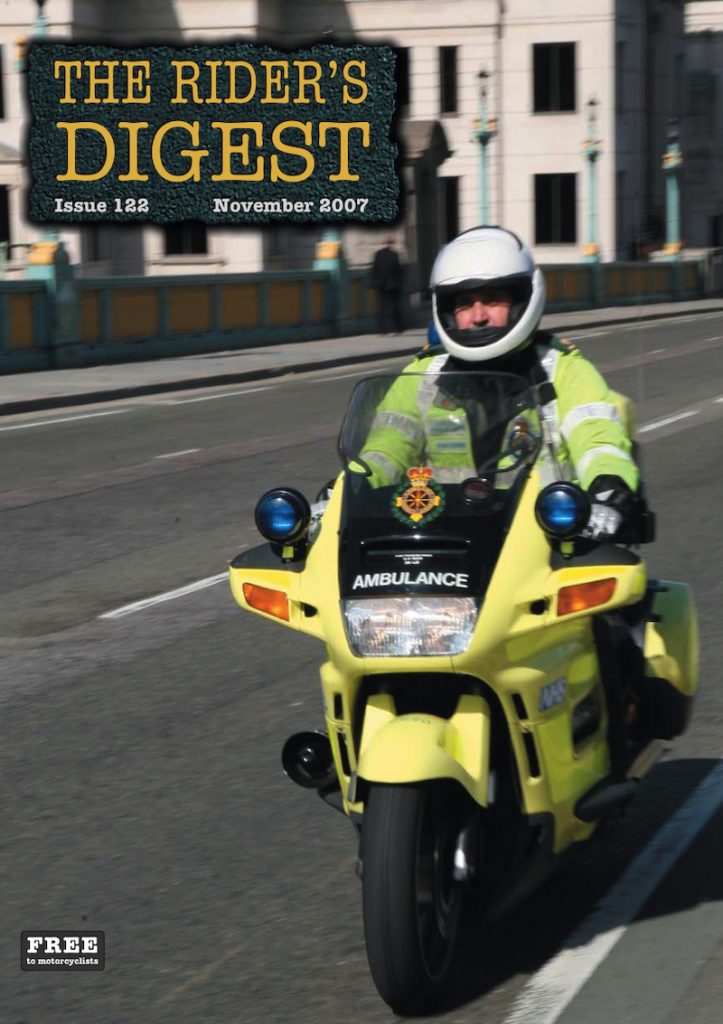

The editor takes a long overdue look at the invaluable service provided by the capital’s Motorcycle Response Units

If you read last month’s Digest, you’ll know that Woffy (Neil Waugh, a dear old friend and more recently a TRD road-tester and key distributor) ended up in hospital along with his wife Pascale after a serious motorcycle accident. The good news is that they are recovering from their injuries; but it could so easily have been a different story.

Apparently Woffy was so badly banged up that the accident had been called in as a fatal. Personnel from all three emergency services rushed to the incident, and thanks to the speed, experience, skill, and dedication they brought to the scene, the reports of Neil’s death turned out to be as accurate as the ones about Mark Twain’s. But he was incredibly lucky that the spot near the Elephant & Castle where it all came on top, is less than 3/4 of a mile from the Waterloo Ambulance Station in Frazier Street, so he had paramedics and a highly specialised Helicopter Emergency Medical Service doctor at his side within minutes of the shout going out.

A Motorcycle Response Unit (MRU) joined them shortly after, having covered the distance from the London Ambulance Service (LAS) station in Bloomsbury in under six minutes. If the accident hadn’t been so close to the LAS head office in Waterloo, the MRU would normally have expected to be first on the scene and delivering life saving care while his colleagues on four wheels were still fighting their way through traffic. On this occasion that wasn’t the case, so the man on the motorcycle quickly joined the rest of the team, adding his expertise to the combined effort that saw my friends in A&E as quickly and safely as was humanly possible.

Three weeks later, as a consequence of a strangely overlapping set of coincidental circumstances, I found myself chatting to MRU Team Leader Shaun Rock – who turned out to be the motorcycle paramedic in question. I’ve admired and secretly envied the MRU’s since I first became aware of them some time in the early 90’s, and I’d been planning to write about them ever since I took over at the Digest. In fact I first exchanged emails with Shaun to that end, back in January 23rd last year; but for one reason or another it never quite happened. Then, the week before his accident, Woffy phoned me to say that he’d been into the Waterloo station delivering their copies of issue 120 and he’d been chatting to the lovely folks there about the terrific job they do, and he thought that I really ought to write about them. I explained that I’d been meaning to do exactly that for over 18 months, and I promised him faithfully that I would get my act together and produce a feature about the MRU’s in issue 122. So in a bizarre twist of fate, it was Neil himself who initiated the chain of events that culminated in me interviewing a man who had been directly involved in administering to him and his wife in their hour of greatest need.

Over a cup of coffee Shaun informed me that the unit was started as a trial in 1991, and it was quickly obvious that motorcycles offered a distinct advantage when it came to delivering paramedic support to the very sickest people in central London where at times the traffic bordered on gridlock.

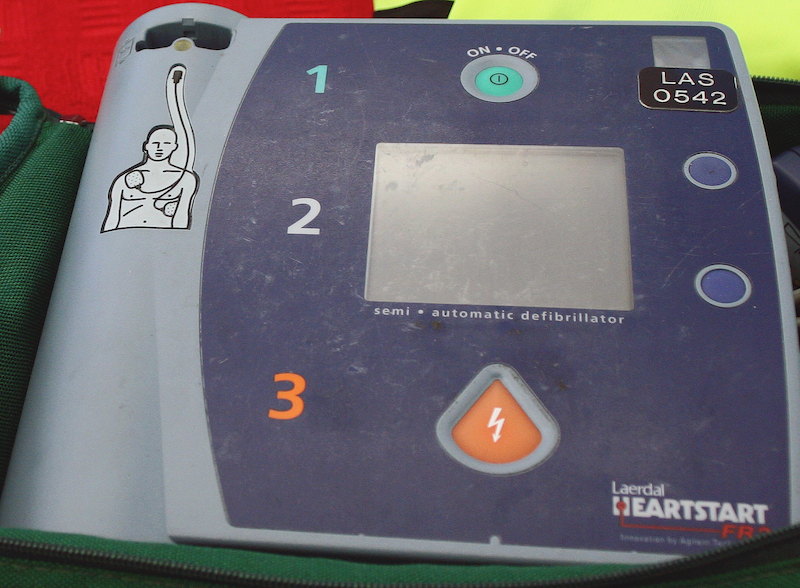

The government requires the MRU’s to get to 75% of category A (i.e. life threatening) calls and have a defibrillator at the patient’s side within 6 minutes; but the unit has its own target of 100%, so on each shift one member of the team stays in the control room looking for suitable calls. As the operator goes through the algorithm the diagnoses pops up on the screen, but the non-operational motorcyclist is listening in, and because of his knowledge base he’ll spot a red job and despatch a rider before it has actually been categorised. Consequently, because they are pre-empting calls, their average response times are actually nearer 3 minutes.

They should only be called out to the very sickest people, people whose lives are actually under threat; but the controller’s experience allows them to read between the lines, so they can often pick up on anomalies that suggest that a patient may be sicker than the green category indicated. If they attend a lower category call they will always be called upon to justify their actions, but they consistently get it right more often than not. This government is obsessed with performance figures and statistics, fortunately the ones the MRU produce, paint a picture that’s bright enough to impress even the most myopic of Whitehall bean counters.

I was surprised to learn that most of the calls they attend are in response to heart attacks and the like, and they aren’t actually sent to many bike accidents. This is because the congestion in their patch slows everything down to such an extent, that they rarely see the sort of high speed incidents that produce injuries which are immediately life threatening (by contrast the helicopter goes all the way out to the M25, so their crews deal with many more RTAs involving two wheelers).

The MRU’s pack an enormous amount of stuff onto their Pan Euros, which puts them right on the weight limit, but all the bikes have up rated brakes and suspension to cope with blue light use. There are certain pieces of equipment, such as the defibrillator, oxygen, and a mask for mouth to mouth, that have to be carried, but outside of those essentials, it is up to the individual what they choose to take with them. Then they either grab the bags out of the panniers and carry them to the patient, or, if for example they find themselves in a busy location like Oxford St, they’d tend to unclip the panniers and take them with them to lay at either end of the area they are working in, to create some sort of physical barrier between themselves and the pedestrians.

None of the bikes have satellite guidance, it all works on personal knowledge, which riders tend to accumulate quickly because they only cover a relatively limited area. But if a rider is new or has any weak spots, he or she would be expected to spend time between calls, taking a grid square out of the map and going back and forth over that sector until they know it like the back of their hand.

Obviously they ride come rain or shine; and because of the volume of traffic and the heat from the buildings, you almost never get ice in central London. The MRU cover from 06.30 to 23.00 at the moment, but they are looking to extend that, because nowadays parts of the West End are heaving 24 hours a day, with the Charing X Rd every bit as congested at 2am as it is at 6pm.

The MRU needs people who are clinically able and whose riding will get them there safely. Their riders are all thoroughly trained by the Met and they are taught to exercise restraint in traffic – that safety is paramount. Riders cannot think that they’re on their way to a terrible sounding call, and become distracted by those thoughts and not concentrate sufficiently on their riding. Although their work is always urgent and they have that 6 minute response time, if the circumstances demand it, they’d rather a rider took a little longer to get there and delivered some treatment than didn’t arrive at all.

Many of the team either come to the bikes from the helicopter, or they go on from the MRU to HEMS, so they have a high exposure to trauma, which can obviously be very dramatic; but Shaun was at great pains to point out that when it comes to saving peoples lives, he and his colleagues are very much part of a well-oiled machine that starts with the operators who take the emergency calls, and includes themselves, the ambulance crews and the A&E staff at the other end.

If anyone fails to understand that, or feels that they are somehow superior to the rest of the wider NHS team they would either be straightened out, or, if that proved impossible, straight out. Shaun spelled it out: “All the boys and girls that work on the unit know how lucky they are, because when you think about it we’re paid quite a good salary to ride a motorbike around central London; to go to people, to be nice to them, to give them some oxygen until a crew turns up to take them to hospital. Now there’s worse jobs for less money, so I say to the boys and girls: look if you have a bad day, just remember just how lucky you are.”

In a world of employment where job satisfaction is at such a premium, how many of you could honestly say that you wouldn’t want to be that knight on a fluorescent yellow charger, who rushes through the traffic with blues and twos blazing, before turning up spectacularly and delivering the gift of life to somebody who is in dire mortal danger?

Dave Gurman

This article first appeared in issue 122 of The Rider’s Digest in November 2007