Beemer Bash

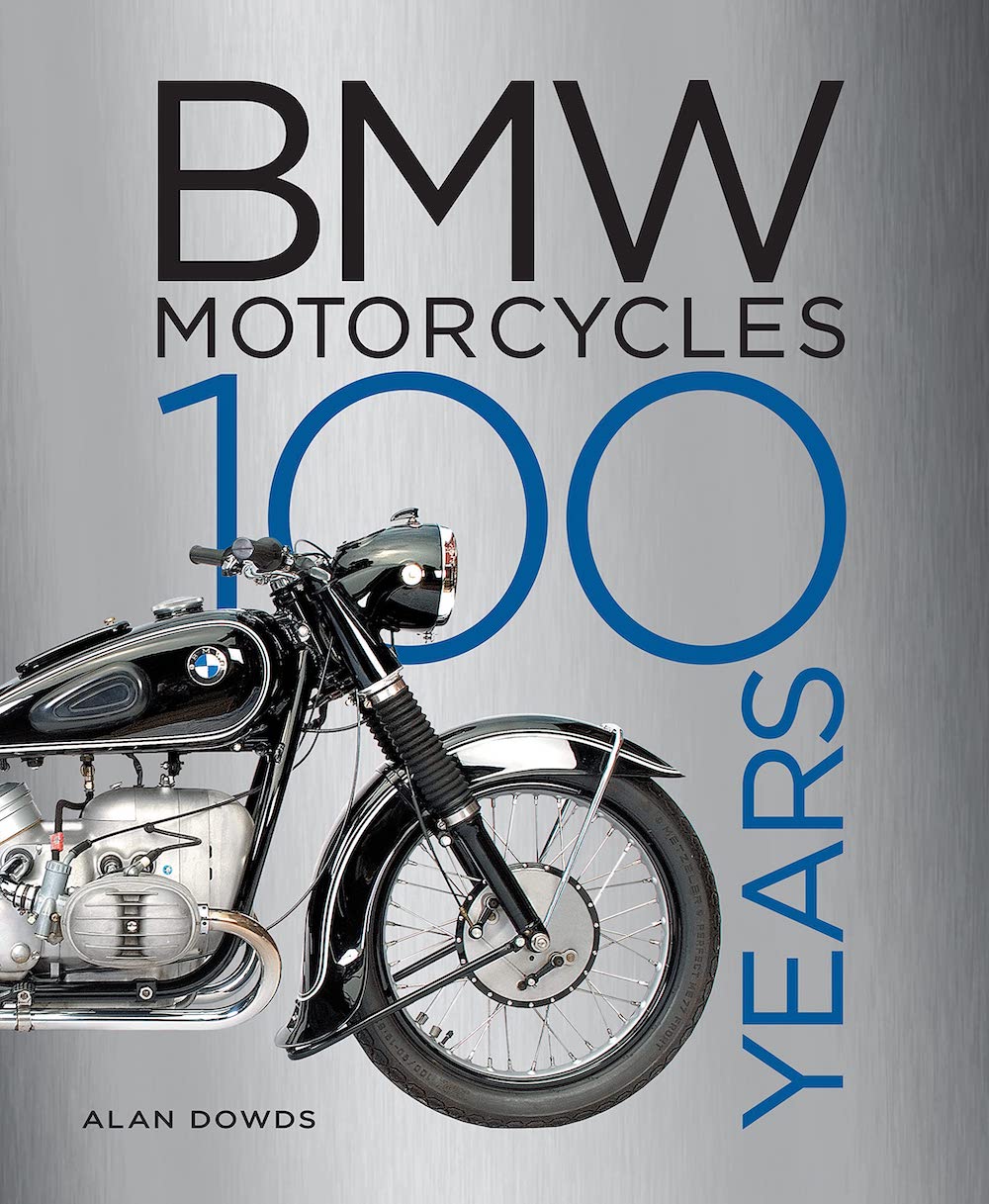

Next year marks the centennial of BMW Motorrad. Landmark anniversaries spawn landmark coverage in the media, old and new. Little wonder Motorbooks has produced BMW Motorcycles: 100 Years by Alan Dowds and released it just in time for 2022’s Christmas sales.

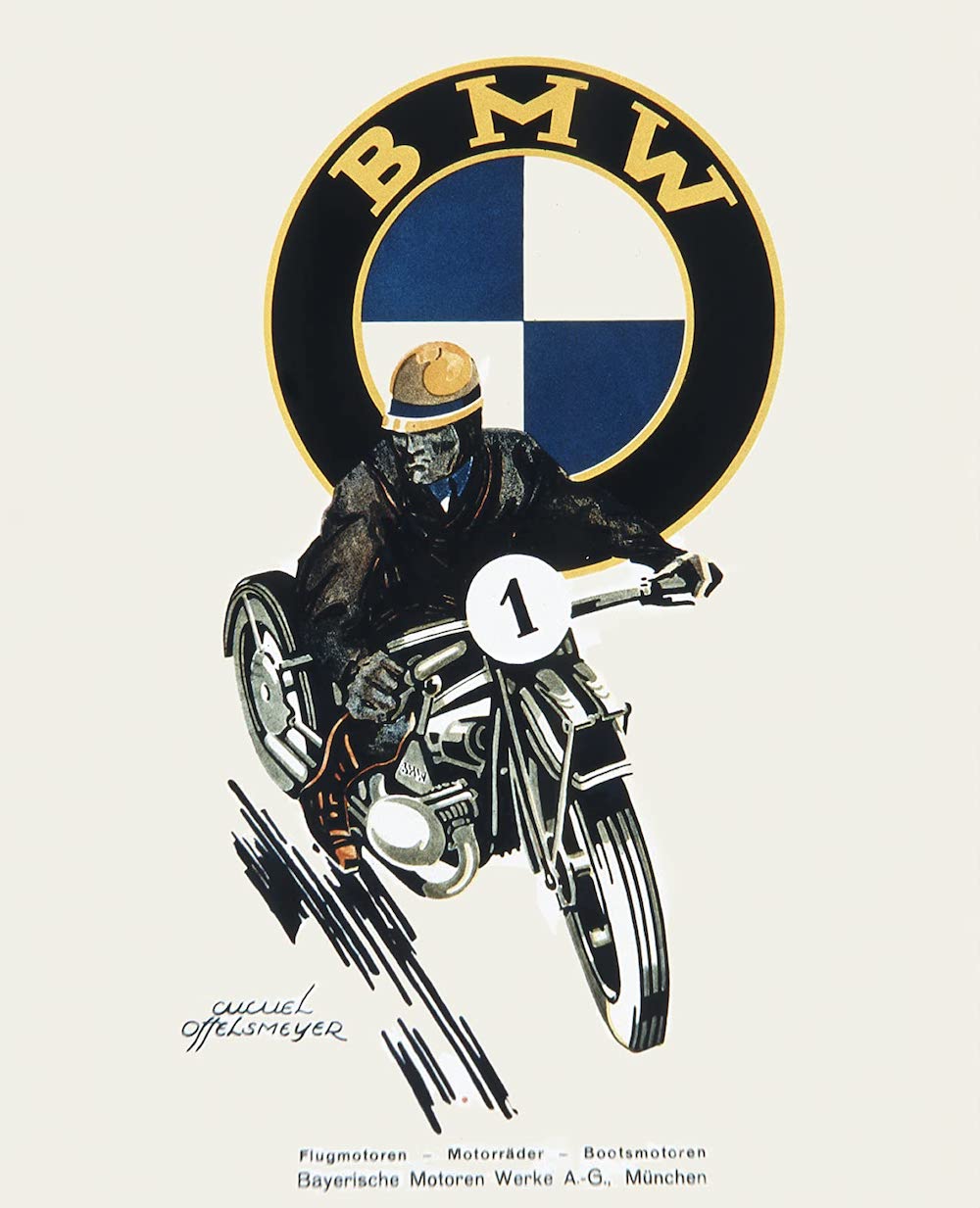

The basic history of Bayerische Motorwerke, or BMW, is fairly well-known. Barred from producing aircraft engines after the treaties ending the first World War, the company turned to manufacturing small portable engines (among other products) which could be and were used for motorcycles. After a few years, BMW merged with Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (1922), whose BFW Helios became the point of departure for the first proper BMW motorcycle, the R32, in 1923.

Some ten years and many, many motorcycles later, the company became an integral part of the German military machine before and during the second World War. In addition to producing the R75, BMW was complicit in both the death camps and the use of slave labor.

Once again, the company was slapped with manufacturing limits and once again motorcycles pulled it through. However, by the late 1950s, it was in financial trouble and in serious danger of being taken over by Daimler-Benz. Instead, BMW was taken over by the Quardt family, who themselves had been early and willing members and supporters of the Nazis. BMW has seen a lot of Reichs and republics come and go since it was founded in 1910 as the Gustav Otto Flugmaschinenfabrik.

Dowds’s book is generically a coffee table book, more about the illustrations than the text. That also means it’s too oversized to take along when you ride as reading matter when you stop for something to eat somewhere. It nearly overwhelmed my desk. Nine of the eleven chapters (plus introduction) divide BMW’s history more or less by decade. The exceptions are bundling the second half of the 40s to the 50s and putting the 60s and 70s together in one chapter. One of the remaining chapters focuses on racing, while the other looks beyond the company’s first 100 years, speculating on a future of safety technology and electric vehicles.

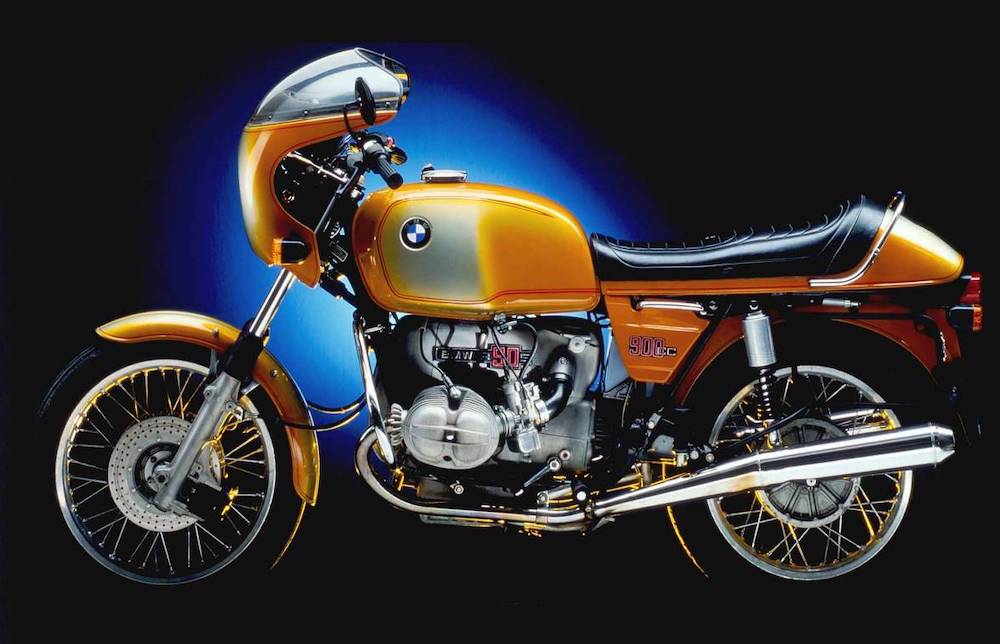

The art direction dictates how the book should be read: captions for the illustrations first; then the sidebars; and last the actual text. Too often, the text or sidebar – and sometimes both — repeat the information in the caption. The illustrations are well selected for Dowds’s bent for technology and superbikes. (He worked at SuperBike for a decade, among his many other credits, which include at least four books about, yes, superbikes.) He’s a professional and the text shows it: it’s brisk, bright, and breezy. If he missed a single production bike, I failed to notice. There are even such “runts of the litter” as the R27 (a favorite of mine, but I like most beemers manufactured between 1955 and 1975); such oddities as the Isetta (the C1 is more interesting); and even includes BMW’s WWII motorcycles with and without sidecars.

But not all bikes receive equal attention. Too many superbikes get detailed attention page after page, picture after picture, paragraph after paragraph. The 310, developed with TVS in India, where the bike is manufactured, is one of the more interesting ideas to come from BMW in the past decade or so. It’s dismissed in two photographs and three short paragraphs. The technical aspects of the bikes are emphasized over the people who decided what bikes get made and what ones remain as concepts or prototypes.

A history of any German firm established before or during the Third Reich has to address the question of what that company did before and during World War II. And that history has to address what the company did after (so-called denazification). BMW’s Nazi history is more complicated than most. The company has its own Nazi past, while its saviours when it almost went bankrupt have one as well, which includes being related to Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda, by marriage. Hitler was best man at the wedding.

Dowds positions BMW as having no choice but to cooperate fully, like any other firm doing business in Germany at that time. He does point out that the company did benefit from forced labor, but again, like any other firm doing business in Germany at that time. While he is not clear on how many such laborers BMW used, he does point out that the total number for everyone was 7.5 million. (I’ve read estimates as high as 12 million, or roughly the same as were killed in the death camps. Let’s split the difference and look at the scale: it’s approximately the same as the population of London.) He goes on explain that BMW has apologized many times, citing three examples. The Quandts themselves have also issued such public apologies, a point not mentioned in Dowds’s book.

Dowds positions BMW as having no choice but to cooperate fully, like any other firm doing business in Germany at that time. He does point out that the company did benefit from forced labor, but again, like any other firm doing business in Germany at that time. While he is not clear on how many such laborers BMW used, he does point out that the total number for everyone was 7.5 million. (I’ve read estimates as high as 12 million, or roughly the same as were killed in the death camps. Let’s split the difference and look at the scale: it’s approximately the same as the population of London.) He goes on explain that BMW has apologized many times, citing three examples. The Quandts themselves have also issued such public apologies, a point not mentioned in Dowds’s book.

But what does all that mean? According to David de Jong, not much. In his well-written and well-researched polemic, Nazi Billionaires (2022), such gestures and apologies are largely empty. As for Herbert and his father, Gunther, (whose ex-wife married Goebbels), de Jong openly calls them war criminals. In an op-ed piece de Jong published in The New York Times about the same time as the book’s release, he noted, “The family’s patriarchs, Gunther Quandt and his son Herbert Quandt, were members of the Nazi Party who subjected as many as 57,500 people to forced or slave labor in their factories, producing weapons and batteries for the German war effort. Gunther Quandt acquired companies from Jews who were forced to sell their businesses at below market value and from others who had their property seized after Germany occupied their countries. Herbert Quandt helped with at least two such dubious acquisitions and also oversaw the planning, building and dismantling of an uncompleted concentration camp in Poland”. De Jong also pointed out that some of those slave laborers worked at Herbert Quandt’s private estate. Parenthetically, the process of buying Jewish businesses at below market prices was called Aryanization.

The point of de Jong’s book is that such German dynasties as the Quandts have yet to fully acknowledge that their ancestors not only willingly collaborated with the Nazis, but also built their fortunes on that collaboration. He wants full transparency and accountability. De Jong feels that so far it’s been slow, grudging, and incomplete.

Dowds is careful to maintain the official story to the point where he cheats the audience of a key part of the BMW story: why did Herbert Quandt take over BMW in the first place? As an experienced financial journalist whose credits include Bloomberg News, de Jong provides the answer: Herbert Quandt liked fast cars. That doesn’t make him any less of a Nazi, but it does make him a Nazi people who like fast motorcycles can relate to. As someone with a background in trade journalism, I found the business manoeuvring to achieve the goal of acquiring BMW fascinating since it also encapsulated the skills Herbert brought to BMW which made the company what it is today. Skills he learned and honed as a Nazi entrepreneur.

But the Quandts and their business decisions that made what BMW is today aren’t the only lacuna here. That’s just the largest and most lurid. While the oft-told story of the Ural being based on the c. 1940s BMW R71 design and technology might be a bit too trivial for the likes of Dowds to mention, surely the 1950s lawsuit between Eisenacher Motorenwerk (EMW) and BMW shouldn’t be. EMW used BMW’s former factories in what was then East Germany to manufacture BMWs of its own. By winning the suit in 1952, BMW could maintain its brand identity and integrity.

And given the importance of the US market to European manufacturing in general and motorcycles in particular in the immediate post-war period, what, if anything, did BMW do to address the casual boycott of German and Japanese goods here in part because of Axis war crimes? A boycott that also existed in Australia, according to a friend from Melbourne. (Curiously, the boycott did not extend to Italy.) It sounds funny now, but at the time it was quite serious and ran well into the 1960s. Did the Regan era tariffs on heavier motorcycles to save Harley-Davidson have any impact on BMW and if so what were they? Honda, for example, produced the Nighthawk 700, making it just “small” enough to escape the tariff. The Nighthawk has since become a cult collectable here in the States.

And given the importance of the US market to European manufacturing in general and motorcycles in particular in the immediate post-war period, what, if anything, did BMW do to address the casual boycott of German and Japanese goods here in part because of Axis war crimes? A boycott that also existed in Australia, according to a friend from Melbourne. (Curiously, the boycott did not extend to Italy.) It sounds funny now, but at the time it was quite serious and ran well into the 1960s. Did the Regan era tariffs on heavier motorcycles to save Harley-Davidson have any impact on BMW and if so what were they? Honda, for example, produced the Nighthawk 700, making it just “small” enough to escape the tariff. The Nighthawk has since become a cult collectable here in the States.

Even more peculiar is that is no mention of Charley Boorman and Ewan McGregor whose Long Way Around (2004) brought greater awareness not only to motorcycle overland adventure travel, but also to such BMW’s dual-sport bikes as the R1150GS used in the documentary series. How many more units did the company sell as a result?

Nazism is not the only larger issue that Dowds evades, if not ignores. The social and ecological issues raised by personal transport vehicles goes unmentioned, which is all but unthinkable for a serious book in this day and age. As for the social and ecological issues of fossil fuels, he provides a glib chapter about technology advances in safety and navigation which includes a few pages about BMW’s electric vehicles (it would have been nice if the CE O4 received a bit more attention).

Nazism is not the only larger issue that Dowds evades, if not ignores. The social and ecological issues raised by personal transport vehicles goes unmentioned, which is all but unthinkable for a serious book in this day and age. As for the social and ecological issues of fossil fuels, he provides a glib chapter about technology advances in safety and navigation which includes a few pages about BMW’s electric vehicles (it would have been nice if the CE O4 received a bit more attention).

Also unexamined are the larger issues regarding lithium ion batteries. China is one of the largest, and perhaps the largest, miner and refiner of lithium, but often with slave labor provided by the ethnic minorities the PRC is trying to repress. The US already has a ban on the import of any products made by slave labor which is expected to have an impact on the price and availability of automotive batteries, among other products. Given the amount of business BMW does with China, has the company learned anything from its own history?

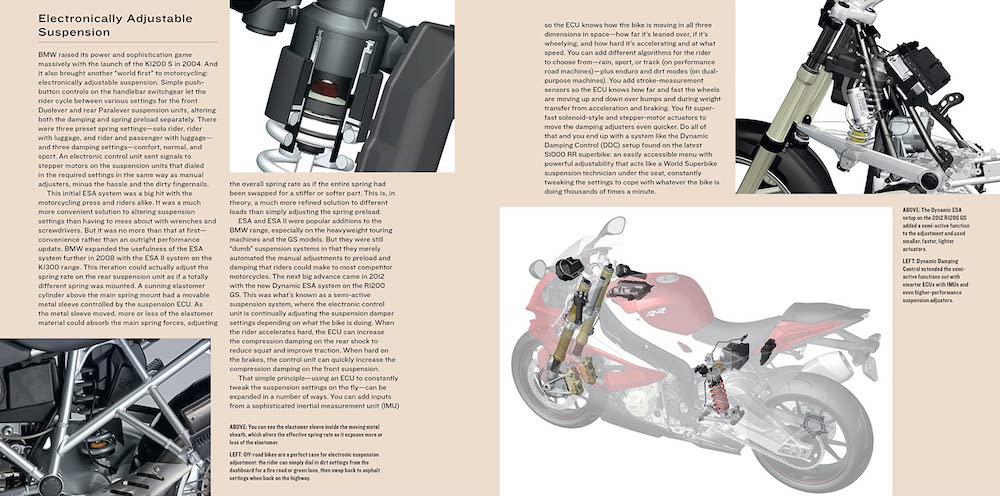

BMW Motorcycles: 100 Years is ideal for anyone who is interested in all things Beemer. I suggested to someone I know that she buy a copy for her father who rode BMWs until an unfortunate encounter with a deer convinced him to hang up his leathers. And despite the book’s limitations it’s a good summary of the actual motorcycles the company has produced over the past century, making it the best book to date for those who want just that one book on BMW, particularly for those for whom superbikes are the be-all and end-all. Those of us who would have preferred a more nuanced and contextual history will have to wait.