Second Verse, Same as the First

Peter Noone shouts “Second verse, same as the first” in one of Herman’s Hermits’s hits in the United States. While never quite as big in the UK as the US, the Hermits once rivaled The Beatles and The Rolling Stones in popularity here. The call-out is from I’m Henry the VIII, I am, which I don’t think was released as a single in Britain.

The number repeats the chorus of the Murray and Weston 1910 pseudo-Cockney music hall song, I’m ‘Enery the Eighth, I am, three times without any of the original amusing and suggestive verses. The call-out comes between the first two rounds of the chorus, which is obvious. Less obvious is that the song was influential on punk rock in general and on The Ramones in particular.

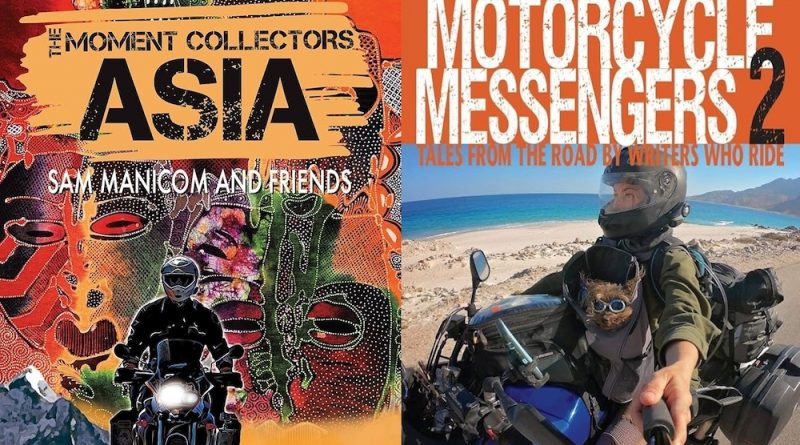

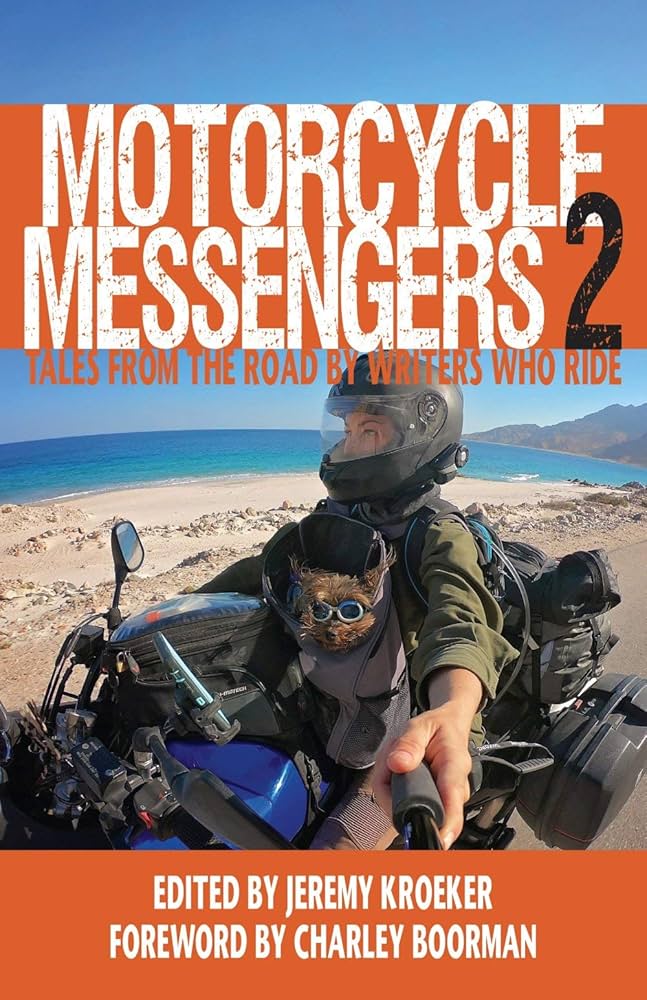

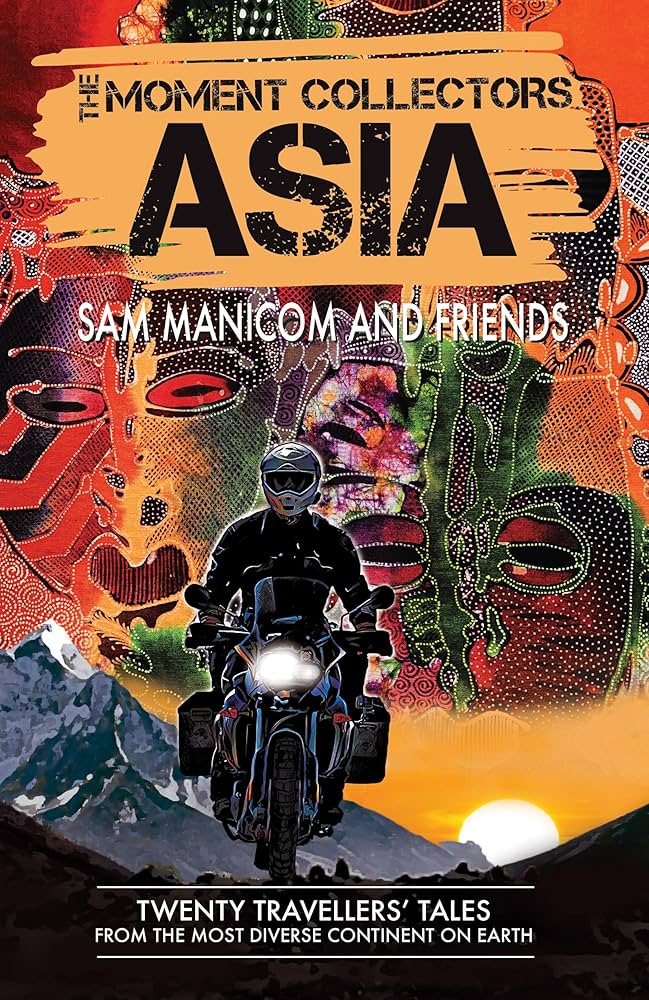

Two books brought this unfortunate earworm to mind: Motorcycle Messengers 2, edited by Jeremy Kroeker, and The Moment Collectors: Asia, by Sam Manicom and Friends. Both follow-up earlier anthologies and both not only resemble their respective predecessors, but also resemble each other. To be fair, they are also, in that classic Hollywood phrase, “the same, but different” on both counts, and that turns out to be a good thing, a very good thing.

Both anthologies continue the overarching conceits that yoked the earlier selections. For Kroeker, it’s that the motorcycle messengers carry the tales of their adventures on the road; for Manicom, it’s that conscious or unconscious “a-ha” travelers have when a place, a person, or an incident reminds them of why they travel in the first place. Of course, the best travelers’s tales come from such moments and without such moments there are no travelers’s tales. Because the pieces are short, the more specific the incident or anecdote, place or person, the better the story. Those that try to cover riding an entire continent tend to read more like summaries than stories. All the fun and telling details are missing.

Both start with the predictable editorial notes and the obligatory celebrity introductions: Kroeker has Charlie Boorman; Manicom, Elspeth Beard. Both celebrities are legitimate choices. Both provide enthusiastic essays. Boorman’s is more exuberant while Beard’s is more cerebral. But the message is much the same. The journey is the adventure and the adventure is in the interruptions, whether a problem to solve or a person to encounter. And, of course, the best journeys are by motorcycle.

Kroeker offers 24 motorcycle messages in 287 pages and Manicom 20 motorcycle moments in 404 pages. Each of Kroeker’s messages begin with title and author, adds sparing explanatory matter only when necessary, goes on to the story itself, and finishes with an author’s bio, which includes social media links. Manicom provides more than that. Each moment starts with title and author, followed by a quote, then the narrative, and concludes not only with a bio and social media links, but also a separate section about the bike and how it was modified for the trip. Each tale also has three illustrations by Simon Roberts: above the title; as a break somewhere in the middle of the tale; and a sketch of the author at the end. Roberts also contributes a moment involving the potential dangers of caricature.

Kroeker offers 24 motorcycle messages in 287 pages and Manicom 20 motorcycle moments in 404 pages. Each of Kroeker’s messages begin with title and author, adds sparing explanatory matter only when necessary, goes on to the story itself, and finishes with an author’s bio, which includes social media links. Manicom provides more than that. Each moment starts with title and author, followed by a quote, then the narrative, and concludes not only with a bio and social media links, but also a separate section about the bike and how it was modified for the trip. Each tale also has three illustrations by Simon Roberts: above the title; as a break somewhere in the middle of the tale; and a sketch of the author at the end. Roberts also contributes a moment involving the potential dangers of caricature.

Some of the quotes slip into pretentiousness; but at the risk of suggesting a conflict of interest, I’ll note that The Rider’s Digest’s own Jacqui Furneaux takes “best of show” for her appropriation of an old Mae West punchline in Manicom’s book. Her quote is probably the least pretentious. And Furneaux is just about the only writer out of the roughly 40 in both books who knows how to make good, and clever, use of quotes, to judge from how she twists an old one-liner from Mark Twain for Kroeker.

Some of the quotes slip into pretentiousness; but at the risk of suggesting a conflict of interest, I’ll note that The Rider’s Digest’s own Jacqui Furneaux takes “best of show” for her appropriation of an old Mae West punchline in Manicom’s book. Her quote is probably the least pretentious. And Furneaux is just about the only writer out of the roughly 40 in both books who knows how to make good, and clever, use of quotes, to judge from how she twists an old one-liner from Mark Twain for Kroeker.

While few contributors are complete unknowns to the overland cognoscenti, Kroeker goes for the big names while Manicom favors writers who are not as well-known as they should be. Both edited the pieces to the rider-writer’s individual styles, which is generally good, although a few stories would have benefited from a firmer editorial pencil.

Furneaux and Manicom appear in both volumes. Other Kroeker messengers include Antonia Bolingbroke-Kent, Ian Brown, Jordan Hasselmann, Liz Jansen, Carla King, Zac Kurylyk, Michelle Lamphere, Ed March, Lisa Morris, Lois Pryce, Mark Richardson, Chris Scott, Simon Thomas, Paddy Tyson, and Dylan Wickrama. Each messenger gets one tale each except Kroeker who once again gives himself three. I went into why that’s tacky in my review of the first volume. Here I would rather emphasize that he includes more than the usual number of Canadian voices. In a sub-genre dominated by British and American voices, that is important and refreshing.

The tales range from Billy Ward being stranded overnight in the African desert, worrying about lions and tigers and bears, to Ted Simon going from sour to serene in Thailand, to Catherine Germillac fielding bullets and chocolates in Colombia. My favorite is Allan Karl dealing with mordida in Guatemala: a short, tight anecdote with a perfect kicker.

Manicom focuses on traveller’s tales from Asia, which he calls “the most diverse continent on Earth” in the subtitle of his anthology. Mongolia and Central Asia (the “Stans”) are the most popular destinations. Chris Donaldson, Heather Ellis, Jeffrey Franz, Heather Lea and Dave Sears, Candida Lewis, Simon and Georgie McCarthy, Carl Parker, Zebb Penman, Paul Stewart, Leigh Wilkins, Sherri Jo Wilkins, and Anita Yusof contribute moments. Manicom, ever the gentlemen, offers only one piece of his own (with Brigit Schunemann) and places it last, letting everyone else have a turn before his. In proper grammar as in proper etiquette, it’s you and me, not me and you.

Here the stories range from Heike and Filippo Fania being among the first motorcyclists to be allowed to travel in Myanmar, to Anatoly Chernyaviskiy riding the ice road of Siberia, to Fern Hume finding taxi drivers a helpful resource when dealing with breakdowns and bureaucracy in Iran. Sheonagh Ravensdale and Pat Thomson’s pleasant tour of South Korea has one of the more interesting reasons to travel: to connect with Ravensdale’s family history as educators and missionaries in the peninsula. And as someone who presents himself as a flaneur, how can I not mention Maria Schumacher and Aiden Walsh, who style themselves as the Coddiwomplers?

Here the stories range from Heike and Filippo Fania being among the first motorcyclists to be allowed to travel in Myanmar, to Anatoly Chernyaviskiy riding the ice road of Siberia, to Fern Hume finding taxi drivers a helpful resource when dealing with breakdowns and bureaucracy in Iran. Sheonagh Ravensdale and Pat Thomson’s pleasant tour of South Korea has one of the more interesting reasons to travel: to connect with Ravensdale’s family history as educators and missionaries in the peninsula. And as someone who presents himself as a flaneur, how can I not mention Maria Schumacher and Aiden Walsh, who style themselves as the Coddiwomplers?

The last section of both books is made up of space ads and listings of other resources; in the case of Manicom, some 34 pages of such material. While this makes projects like these financially viable, it also raises two other important points. As I noted in my review of the first Moment Collectors, “the revenue model is closer to that of a newspaper or motorcycle magazine: deliver an audience to an advertiser. Given the expense of (self-)publication, it may well be the wave of the future. Right now, it makes The Moment Collectors an indispensable resource for overlanders”. It also creates the potential for conflicts of interest.

Whether you want to call them moments or messages, not all such tales are suited to full-length books. Many of them are best told in short form. Yet, anthologies such as these are rare. And while short-form travel narratives are one of the mainstays in motorcycle magazines, those published tales are usually not collected and older ones are too often not even digitalized. There is a need for more anthologies about motorcycle messengers, more anthologies about moment collectors.

Regardless, either Motorcycle Messengers 2 or The Moment Collectors: Asia – or ideally both – will make great holiday gifts, whether under a tree or in a stocking.