The Ace Cafe, Café Racers, and Racing Aces Pt. 1

It is doubtful that there is anyone involved in the world of British motorcycling whose life is not touched directly or indirectly by the Ace Cafe. A visit here, an experience there, and it’s another tale to tell, adding to the legend (if not the reality) of the Ace.

That’s true even for those of us living in the States. In my case it happened a couple of years ago when I was nattering with Dave Gurman, The Rider’s Digest editor and Fearless Leader. The Ace came up and he informed me loftily that in Britain in general and at the Ace in particular, not only did café not have an accent aigu, but also it was pronounced as one syllable: caff.

The pronunciation didn’t bother me. We are talking about a culture that pronounces Elgin with a hard G; Dulwich as if it were spelt “dullich”; and Cholmondeley, which looks as if it should rhyme with to Mandalay, to rhyme with Mumley.

Nor did the lack of an aigu in contemporary British English bother me. It’s fading in the U.S. as well. Résumé, for example, has already lost the first aigu here and I’ve seen it printed without the second as well. There is now little difference between resume and resume.

No, it was the physical aigu itself on the Ace’s sign. I did my graduate work in design and architectural history. My visual memory is better than average (at least for the built environment). I remembered seeing an aigu in a photo of the Ace. What happened to that accent mark? When did the Ace undergo an aiguectomy? And was it painful?

The missing aigu is only one of the questions, major or minor, that are sometimes answered, sometimes not, in books about the life and times of café racers. Looking at such books chronologically is an interesting exercise in seeing how the legend of the Ace has been assembled, deconstructed, and, ultimately, co-opted as a nostalgia machine.

And a very particular nostalgia at that: ‘nostalgie de la boue’. Roughly speaking, the phrase means yearning for the mud puddle. It comes from an 1855 Emile Augier play about a prostitute who marries a nobleman, but, try as she may, keeps returning to her old habits. Despite that rather unfortunate reactionary rejection of human improvement or redemption, the phrase continued, but by the turn of the century took on the meaning of liking a bit of rough. By the end of the twentieth century, nostalgie de la boue morphed again to mean a sort of slumming, a yearning for real or imagined illicit pleasures, a Lou Reed style Walk on the Wild Side, although not necessarily

just sexual.

For our purposes, the phrase means yearning for the wicked youth one wishes one had, as long as it’s not too wicked. The slight shift reflects a second quality in these books: a sense that the café racers lead a more authentic existence. Authenticity is always in another time, another place, another culture, sometimes less sophisticated, if not more primitive.

For our purposes, the phrase means yearning for the wicked youth one wishes one had, as long as it’s not too wicked. The slight shift reflects a second quality in these books: a sense that the café racers lead a more authentic existence. Authenticity is always in another time, another place, another culture, sometimes less sophisticated, if not more primitive.

Another quality these books have is that they are ‘coffee table books’. Back in grad school my thesis focused on coffee table books devoted to regional interior design styles, English Country style, say. I don’t know whether I’m pleased or appalled that motorcycle coffee table books are little better.

The checklist for a proper coffee table book includes lots of pictures, an introduction by someone somehow significant or relevant to the subject, and an implicit catalogue and directory to purchase or recreate the look. To be fair, in the motorcycle coffee table book the celebrity writing the introduction invariably has a more legitimate connection to motorcycling than the celebrities drafted for design books – which are neither well written nor well researched. Again, to be fair, because of the nature of the niche market, the motorcycle variety are sometimes better researched than, well, the design books. Sadly, that doesn’t mean they are well-researched.

In the roughly quarter century since the first one, at least eight books have been published about the culture and they are all lavishly illustrated. Barely a page doesn’t either have or face a picture. Earlier books have black and white photos, while later ones favorcolor shots. Celebrity introductions cover the range: Dave Croxford, Dave Degens, and the Reverend William Shergold, among others.

While not well-researched usually means shallow or journalistic, in this case, it also means riddled with mistakes. The mistakes range from the general – getting the year the U.S. entered World War II wrong – to the specific – using a photo of the second Ace Café when the first is meant – to the tangential – claiming that Edith Piaf’s classic L’homme à la moto is a French song (it’s an American song, Black Denim Trousers and Motorcycle Boots, written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, and originally recorded by The Cheers, a year or so before Piaf; to be fair, Piaf owns that song in a way The Cheers never did and never will). A routine fact-check could have cleaned up most of these. A routine Google will generate a longer list of even more amusing mistakes.

Getting back to nostalgia, authenticity, and, last, but definitely least, the mystery of the aigu, the first settles in pretty fast. Soon after the original Ace closed in 1969, a second Ace opens, closer to the center of London, and frequently misidentified as the Ace we think of when we say “the Ace”. In 1973, nostalgia arrives properly when Martin Craig released Rockin’ at the Ace Café, pronounced in the song as “kaffay”.

Getting back to nostalgia, authenticity, and, last, but definitely least, the mystery of the aigu, the first settles in pretty fast. Soon after the original Ace closed in 1969, a second Ace opens, closer to the center of London, and frequently misidentified as the Ace we think of when we say “the Ace”. In 1973, nostalgia arrives properly when Martin Craig released Rockin’ at the Ace Café, pronounced in the song as “kaffay”.

The earliest book, however, seems to be Johnny Stuart’s Rockers! (1987). Although the volume has become known as the most shoplifted book in London, Stuart, who died in 2003, had a more respectable reputation as a pioneering expert in Russian art. “This is not a book about bikes”, he asserts (p.6). And indeed it is not. It is about a lifestyle and street style in which motorcycles played a significant part.

Rockers! is lavishly illustrated. There are 170 black and white photographs jammed into its 126 pages. The endpapers are a wonderful selection of vintage ads illustration the archetypal rocker’s street-style look. The cheap production values are overwhelmed by what is clearly a labor of love.

Stuart met and interviewed people who were part of what he calls the “epic phase” of rockers/café racers: the early 50s to the early 60s. It was a time when “English habits” mixed with “American dreams”. He draws upon his background in the visual arts to connect various political and economic trends to the rocker street style he adores.

The relative affluence following the post-war recovery made suburban working-class life comfortable and conformist as well as boring and alienating. It not only turned the teenager into a rebel, but also made the two categories indistinguishable. Thanks in part to motorcycles and rock and roll, revolt turned into style, identity

into ritual.

Large sections of the book are devoted to how a working-class style evolved into the “mean and nasty” look of the rocker/leather boy. Stuart sees the cowboy look of the bike boys (he uses just about any and every term except bikers) as leather jackets, “drain pipe” jeans, and broad leather belts (the better to rumble with). Little wonder he was both a lender and an advisor to the “British Street Style” exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1994, the year that launched the renaissance of the café racer.

Part of the energy behind the street style was rock and roll, which Stuart credits to the American music scene of the time in general and Elvis Presley in particular. Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, and even the Beatles are considered as well. For Stuart, the street style credibility of these performers ends when they reach a certain level of popularity. If they attain genuine popular success it is only because they have been castrated. I haven’t encountered so much wholesale castration since the local veterinarian offered a special on spaying or neutering house pets.

Despite the disclaimer, Stuart does address motorcycles, even if he doesn’t wax poetic about this marque or that. He notes that the rockers were seen as unimportant or embarrassing to the then motorcycle manufacturing establishment, which favored the older tweed and flannel enthusiast. As for the rockers, they went and built the sort of bikes the manufacturers might have made if they wanted to sell to the niche that wanted fast and cheap transport. Of course, Stuart connects this back to images of such American actors as James Dean and Marlon Brando on motorcycles.

The biggest strength of Rockers! is the photography. In the acknowledgements, Stuart notes that few bothered to photograph the rockers and what did exist was not available. He gets peevish about not being able to access Diane Arbus’s images. Why use of her photographs was forbidden is unknown, but he might have thanked whoever was that shortsighted. It forced Stuart to dig deeply into private albums and obscure collections to produce the archives he hoped to find. The pictures here are used and reused again and again in most subsequent books about café racers. This is the mother lode.

In terms of research, Stuart’s done his homework. The pictures alone guarantee that. His narrative style is unfortunate. He gushes like a tabloid queen, which is bad enough, but when he asserts that much of the bad boy reputation of the rockers is due to media exaggeration, it’s worse. He’s complaining about an approach he is using himself to generate and maintain interest.

In terms of research, Stuart’s done his homework. The pictures alone guarantee that. His narrative style is unfortunate. He gushes like a tabloid queen, which is bad enough, but when he asserts that much of the bad boy reputation of the rockers is due to media exaggeration, it’s worse. He’s complaining about an approach he is using himself to generate and maintain interest.

Stuart seemingly can’t refer to the Ace without calling it notorious (e.g., pages 49 and 55 for a start). To be fair, he also describes the Dragon Rally in Wales as notorious (p.93). On the other hand, record racing (attempting to cover a specific route before a particular disc finishes playing on the jukebox), which might actually be legitimately described as notorious, is dispatched in a couple of sentences, surprisingly free of any adjectives, pejorative or otherwise (p.59).

Worse is his use of uncredited quotes. This is a no-no in both academic and journalistic circles. Without saying who said something, there is no way of checking whether someone actually did say it or whether Stuart made the quote up himself.

Stuart was on the outside looking in. Mike Clay was on the inside looking out. He was a café racer and his 1988 book, Café Racers, is written unabashedly from that point of view. While Stuart’s book may not have been about bikes, Clay’s is, and more.

True to the coffee table archetype there is a celebrity introduction, in this case from the Reverend Bill Shergold (of 59 Club fame). It’s organized as if it were a sermon. Instead of moving back and forth between one observation or another and a line of scripture, Shergold moves between his public and private history of motorcycling and Clay’s book. Too many introductions can’t seem to be bothered to even mention the book or the author being introduced.

Little wonder Shergold enjoyed a reputation as quite the charmer.

As for the charm of café racers, it was more than just turning the handlebars down or knocking the baffles from the silencers. Clay quotes a friend: “Café racers? They don’t come out of factories, they come from blokes’ garages and garden sheds, don’t they?” Not to mention bedrooms and kitchen tables. (British mothers are apparently much more indulgent with their offspring than American ones.)

Clay conveys the ingenuity and hard work that went into the café racers. He discusses modifications he’s done and modifications he’d like to do, from BSA Goldstars to Tritons and beyond. He cites slipper pistons and Superleggera fork conversions for Goldies; devotes three pages to how he might create the ultimate Triton (p.84-86); and even speculates on a Norton/Harley-Davidson hybrid (p.139) in which a Harley engine would be slipped into an old Featherbed frame, with Matchless heads and barrels. By the end of the book, the reader will know how a café racer thinks.

Clay conveys the ingenuity and hard work that went into the café racers. He discusses modifications he’s done and modifications he’d like to do, from BSA Goldstars to Tritons and beyond. He cites slipper pistons and Superleggera fork conversions for Goldies; devotes three pages to how he might create the ultimate Triton (p.84-86); and even speculates on a Norton/Harley-Davidson hybrid (p.139) in which a Harley engine would be slipped into an old Featherbed frame, with Matchless heads and barrels. By the end of the book, the reader will know how a café racer thinks.

He also covers the major aftermarket players – Paul Dunstall, Ian Kennedy, and John Williams, among others – as well as café racers who went on to fame and fortune (not necessarily as racers) – Paul Smart, Griff Jenkins, and Ray Pickrell, to name a few. Clay even goes as far as to look at superbikes and production café racers, declaring that the Ducati 750 SS is the ultimate café racer (at least at the time of publication; but no argument here).

Despite the emphasis on the bikes themselves, Clay does cover a great deal of the lifestyle and street style. He presents the riding kit, with its RAF jackets and flying boots, as more flyboy than cowboy. (Personally, I’d say it’s always some mix of the two.) He traces the history of café racers back to the 30s, with the Promenade Percys and such hangouts as the Tram.

Clay picks up the post-war history with his own hangout, the Busy Bee. Not that the Ace wants for attention, even if it is described as notorious on page 116 and misidentified on page 13 (the photo is of the other Ace). He also tackles the question of record racing, for which he claims the Ace was foremost and most likely first. He goes one to outline the route, speeds, and gear changes necessary to pull the trick (p.37-38). While Clay is not above accusing the media of sensationalism when reporting on the excesses of café racers, in this case he opts for a restrained comment that all the BBC did with Dixon of Dock Green was keep it alive.

Clay picks up the post-war history with his own hangout, the Busy Bee. Not that the Ace wants for attention, even if it is described as notorious on page 116 and misidentified on page 13 (the photo is of the other Ace). He also tackles the question of record racing, for which he claims the Ace was foremost and most likely first. He goes one to outline the route, speeds, and gear changes necessary to pull the trick (p.37-38). While Clay is not above accusing the media of sensationalism when reporting on the excesses of café racers, in this case he opts for a restrained comment that all the BBC did with Dixon of Dock Green was keep it alive.

He’s less interested in the classic mods and rockers conflicts, tossing the series of incidents into a chapter that also includes road accidents that resulted in decapitation. There is also mention of a Rose Sheppard whose scrapbook included lists of dead bike boys. More interesting is a brief mention of fights between rockers and squaddies, with which I am unfamiliar and which has not been cited in the other books.

In a way the book is less a history than a memoir, with some valedictory asides. “Here and there an odd survivor, like myself, rode on alone for another year or two, but without the camaraderie, of which all old café racers speak, the joy was gone, and the rebirth was still some years to come”, he notes (p.72).

Café Racers is out of print and has become something of a collector’s item. Mike Seate claimed in 2008 that a copy could command as much as $300. I picked up a copy about the same time for one-fourth of that, but it was at a vintage motorcycle show and items were priced “to go to the right people”.

Café Racers is out of print and has become something of a collector’s item. Mike Seate claimed in 2008 that a copy could command as much as $300. I picked up a copy about the same time for one-fourth of that, but it was at a vintage motorcycle show and items were priced “to go to the right people”.

The rebirth Clay refers to has more to do with the classic motorcycle scene than with what we now know happened barely six years later. 1994 was a seminal year in the café racer revival. Not only did Mark Wilsmore arrange the first Ace Café reunion, but also the racer/rocker look was featured in the V&A Street Style exhibit. Little wonder Mick Walker produced not one, but two books on the subject that year.

Walker enjoys a unique position in the world of motorcycle journalists: beloved and prolific. With some 130 books to his credit, he was virtually a small manufacturing firm. As usual with that high an output, quality control was sometimes a question. Between half and two-thirds of his oeuvre could be described as typical or average Walker, with the balance unevenly split between above and below par.

The 2010 printing of Café Racers of the 1960s, A Pictorial Review is a compilation of poorly reproduced pictures with lengthy captions, grouped by theme or subject, each introduced with a brief paragraph. It feels hastily slapped together to cash in on the then current interest in café racers. Worse, it was a missed opportunity for something more interesting. Walker himself was a café racer (as Clay points out). Nevertheless, Walker does note wryly that it was after one crash too many he decided it was safer to race on a track.

The 96-page book is not totally without merit. He organized the history of café racers into three parts and was likely among the first to see the last phase as predominantly North American. The short section on rockers is long in family album photographs from Tom Thompson. The strongest sections are on aftermarket goodies and the major customizers. Walker also remembers to include such foreign contributors as Ossa, Parilla, and Bultaco, describing them as “racers with lights”.

On the downside, given that the book is all about the captions, there are some major errors. The wrong Ace is shown on pages 48-49. Too many people in photographs are listed as unknown (though I’ll give him a free pass for the humor of “Burt (surname now forgotten!)” for the cover shot).

Walker follows up with Superbike Specials of the 1970s, which was reprinted as Café Racers of the 1970s. In broad terms, this focuses on the third phase of the café racers. Photos are drawn from his personal collection (and are slightly better reproduced). Too many feature charming young ladies posed along side this motorcycle or that. While the young ladies are all properly posed and dressed, the culminative effect is that that you’ve stumbled across someone’s private stash of porn.

Walker follows up with Superbike Specials of the 1970s, which was reprinted as Café Racers of the 1970s. In broad terms, this focuses on the third phase of the café racers. Photos are drawn from his personal collection (and are slightly better reproduced). Too many feature charming young ladies posed along side this motorcycle or that. While the young ladies are all properly posed and dressed, the culminative effect is that that you’ve stumbled across someone’s private stash of porn.

The book is essentially a catalogue of the major after market customizers of the 70s. Dunstall, Rickman and Dresda all get their turn, as do Read Titan, Van Veen, and Gus Kuhn. Asides for the rotary engine or such oddities as the Quasar (p.93) make the 94-page book feel padded. And without the spine of the rockers and the transport cafes, it remains

little more than a glorified listings directory.

In terms of the reprints, digital technology is sufficiently advanced and cost-effective that the photographs could have been cleaned up without compromising their integrity. Combining the two books into one volume – even if given the unwieldy title of Café Racers of the 1960s and 1970s – might have made the second book feel less list-like and strengthened the point in the first book about the 70s being the then most recent phase of café racers.

To pick a minor example, noting in the first book that a black leather jacket, boots with white socks folded over the top, and pudding basin or jet helmets were typical of the 1960s café racer is not uninteresting, but becomes more so when matched with a comment in the second about the passage of time leading to a change in costume: the helmet and goggles being replaced by full-face helmets and full leathers if not a one-piece racing suit. (It could be argued that the first is really the 1950s and the 60s were the transition to what become commonplace in the 70s.)

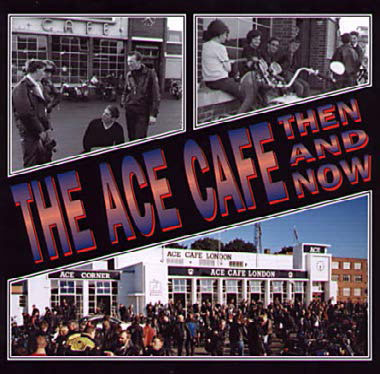

The Ace reopened in 2001. 2002 saw the publication of The Ace Cafe Then and Now, edited by Winston Ramsey. While the Ace had been covered in the previous books, this is the first that puts the cafe front and center, and without the aigu.

The Ace reopened in 2001. 2002 saw the publication of The Ace Cafe Then and Now, edited by Winston Ramsey. While the Ace had been covered in the previous books, this is the first that puts the cafe front and center, and without the aigu.

The Ace Cafe was produced by After The Battle, an imprint that specializes in an odd form of military history. The books are a mix of period clippings on a battle or battlefield, maps and photographs of what a place looked like then next to a picture of what it looks like now, and oral histories (or personal reminisces). Typical titles are The Zulu War Then and Now, Gallipoli Then and Now,orThe War in the Channel Islands Then and Now. Non-military titles include Scenes of Murders Then and Now and On the Trail of Bonnie and Clyde Then and Now.

The publishing house’s fondness for war and true crime explains in part why it doesn’t begin with the opening of the Ace in 1938, but a good ten years earlier with the plans and construction of roads designed to carry motorized traffic, plans which include transport cafes. The tale is told through a selection of contemporary clippings rather than summary and analysis. Even Johnny Stuart gets quoted, but not for saying the Ace is notorious. That honor goes to an anonymous press report about the closing of the original Ace in 1969.

The publishing house’s fondness for war and true crime explains in part why it doesn’t begin with the opening of the Ace in 1938, but a good ten years earlier with the plans and construction of roads designed to carry motorized traffic, plans which include transport cafes. The tale is told through a selection of contemporary clippings rather than summary and analysis. Even Johnny Stuart gets quoted, but not for saying the Ace is notorious. That honor goes to an anonymous press report about the closing of the original Ace in 1969.

Through the selection of press clippings and interviews, Ramsey obliquely suggests that rockers and café racers suffered prejudice from both the upper class courts and the working class press. He includes several scenes from the 1961 script for The Burn-Up episode of Dixon. In a caption, Ramsey stresses record racing never happened. A section about a routine article in Today emphasise that the cover shot was posed.

The maps and the then and now photographs have a narrative of their own. The photographers go to great pains to get as exact a matching new shot as they can, succeeding much more often than not. Readers who like this sort of thing will have hours of fun pouring over every detail. I’m one and I did.

The heart of the book however is an extended oral history of the Ace from Barry “Noddy” Cheese who was a regular from 1958 to 1962. In addition to posing in front of now shots of places shown in companion then photographs, Cheese manages to evoke something of what it must have been like to be one of the faster ton-up boys. On page 90 he swears “record racing never happened”. One of Ramsey’s picture sources is Clay (Stuart is another).

Also entertaining is a shorter section in which film buff Mark Metcalf poses in front of the various locations used for The Leather Boys. Motorcycle songs are also discussed, though the section shot through with inaccuracies. The Shangri-Las, who recorded Leader of the Pack, are said to have graduated from Jackson High School. They graduated from Andrew Jackson High School. Ramsey also wonders why it is rare to have a picture of all four. The answer is one hated touring. On the other hand, he gets a lovely quote from Craig about his connection to the Ace and the origins of Rockin’ at the Ace Cafe.

The Ace Cafe takes a serious turn with motorcycling death statistics and inquests, culminating in the presentation of a Remembrance Book to Mark Wilsmore (billed as “the saviour of the Ace”) to be kept at the Ace to record the names of those who were killed because of “their love of speed”.

Now the remembrance of fallen comrades at arms is a mainstay of military culture. Given After The Battle’s stock in trade, it is easy to see why it presented the Remembrance Book. However there is a difference between being killed for a cause or one’s country and being killed for the thrill of edge play, seeing how far (or fast) someone can go and still come back to tell the tale. The edge players do deserve to be remembered, but perhaps there is a better way to phrase or present the concept.

Alastair Walker’s The Café Racer Phenomenon (2009) so perfectly matches the checklist for a coffee table book it ought to be preserved as a textbook example. Here’s the generic celebrity introduction, there’s the breezy narrative, and bringing up the rear is the directory of parts and services for recreation or restoration.

The introduction is by Paul Dunstall. The bulk of the section is his memories of the heyday of the café racers. At the end he writes, “I hope this book brings back happy memories for older riders and gives younger bikers a glimpse of a more carefree time”.

That’s right: he introduces a book without mentioning the title or the author. Nor is the book referenced in the earlier, more personal paragraphs. It could introduce any – or all – of the eight books discussed here. Actually, it could introduce any motorcycle history book published to date.

As for the history, it samples the essentials. The Ace opened in 1938; it was bombed in 1940; it was rebuilt and reopened in 1948. In 1994, 25 years after it closed in 1969, Wilsmore arranged the first Ace Reunion. The event was so successful, he decided to try to revive and reopen the Ace itself, which he finally did in 2001.

Oral histories from this or that aging or former café racer enliven the narrative with personal anecdotes. Some café racers are misidentified. Worse, so are the aftermarket goodies with which they customized their racers. Rockers and rock and roll get their brief due, as does the Busy Bee.

Wilsmore is called in to be the voice of Ace/café racer history, which he does very well, playing down any elements, which traditionally have been presented as sensationalized. The Reverend Shergold and the 59 Club are dropped

in to show the café racers were really good guys at heart. Customizers and aftermarket merchants get their spotlight. Contemporary color photographs are favored over archival black and

white ones.

If all that sounds a little dull, it is. The best parts of the book are the directories, one historic, one contemporary, of aftermarket parts, services, and specialists. The contemporary list makes no claims to be complete, but it would be a good place to start for anyone interested in building his or her own café racer.