Beginnings: Fits and Starts

Where, oh where, to begin discussing Ashes to Boonville by Geoff G. Thomas?

I could begin with why it wasn’t reviewed in November as originally planned.

Or I could begin with the series of absurd events including (but not limited to): my mother’s two visits to the hospital; jury duty; a germ that decided I was its new home for a fortnight, only to return a week later for a second visit; and packing the selfsame mother up as well as sending her off to the Caribbean for the winter, only to discover that her house had been burgled almost as soon as she left town. The police were very nice; the insurance company, not so nice; the burglars, not at all nice.

Or I could begin with getting an official reviewers copy – always welcome – with a cover note – always standard – with a request that I “be kind”. I come out of the academic tradition of reviewing. Reviews are neither kind nor unkind; they are either fair or unfair. A proper review, as A.O. Scott of The New York Times observed, is “well defended and cogently argued”. Scott also calls reviews “subjective judgments”, as if there were reviews that are “objective judgments”.

Adding to the merriment, Geoff Thomas sent me not one, but two LinkedIn invitations, which raised the conflict of interests issue beyond that of his being a fellow Digest contributor. Not only was an earlier version of Ashes published in The Rider’s Digest as a monthly column ‘live’ from the road, but also Thomas continues to contribute pieces, such as his list of key motorcycle adventure books (issue 164), which is highly recommended as a place for people to start their own reading in the sub-genre.

I suppose because he claims to be dyslexic and I’m borderline dyslexic (as well as borderline ambidextrous) there is a basis for a professional relationship. At least among those who sometimes literally can’t tell their thgir from their tfel. Despite feeling a bit stalked, I finally accepted the connection. This was not the right time or place to mount my soapbox about ethics in motojournalism.

Or I could begin with his association with Ted Simon and his circle. Thomas is one of the more recent Jupiter’s Travelers. Simon himself saw fit to endorse Thomas on the Ted Simon Foundation web site: “’Ashes to Boonville’ is a winner. It’s refreshing to read something so well written”.

Sam Manicom, a Foundation Advisor, adds “Geoff Thomas introduces you to the lands and people along the way with vivid descriptions and a refreshingly openhearted manner”. (Self-disclosure 1: Manicom is a Facebook friend.)

Thomas in the Acknowledgments thanks Simon and Manicom (not to mention The Rider’s Digest) as well as Bernard Smith and his late wife Cathy, whose recent death saddened the entire motorcycle adventure riding community. And, inevitably, Thomas began and finished his around the world trip at the Ace Cafe.

Or I could begin with the fact that Ashes is the first book in a projected trilogy and quote Oscar Wilde about three-volume works: “All it takes is a complete ignorance of Art and Life”.

I first came across that quote in the Afterword in Samuel R. Delany’s omnibus edition of his Fall of the Towers trilogy, which he first wrote and published when he was about 20 and I first read when I was about 12. (Self-disclosure 2: years later I took a course in science fiction writing that was taught in part by Delany.)

Delany was being both dismissive and tongue-in-cheek about his juvenile effort. Both Thomas and Delany have good reason to be more serious. Homeward Bound and The Accidental Pilgrim are the titles of the next two volumes of the Poor Circulation trilogy.

Or do I begin with Thomas’s stated ambition: “I hope that Ashes to Boonville will read more like a novel than a hastily written travel journal” and discuss his travel narrative in the context of whether it achieved the level of narrative power a novel has.

Usually that is the province of travel writers who stay for months if not a year or more in one place: Peter Mayle, say, or Frances Mayes, to cite two perennial best-sellers. For writers of transportation rather than destination, Paul Theroux or Bruce Chatwin might be good examples.

Regardless, Thomas would seem to be aiming higher than writers of motorcycle adventure narratives usually do. Asking whether he measures up to his ambition is a legitimate critical question.

Thomas himself mulls the question of where to begin at the start of Ashes and picked the exact wrong place.

Thomas is an ex-dispatch rider turned world traveler with literary aspirations. Before Ashes begins, he had racked up close to a million miles on motorcycles, though he points out wryly, being a motorcycle messenger sucks the fun out of riding.

Adopted almost at birth, Thomas was brought up by parents who did a fair amount of traveling with and without two children in tow, or at least in a sidecar. They couldn’t afford much more. A graduation gift of Simon’s Jupiter Travels started the around the world bug, but nothing came of that for decades.

After his mother died and was cremated, Thomas and his brother discovered she had kept the urn with their father’s ashes in the back of a closet. Thomas remembered how taken she was with the Pacific Coast in general and Mendocino County in particular, where his brother lives. Somehow that merged with his old dream of going around the world and he decided to take his parents on one last trip to places they had been and places that they would have liked to have gone, ending up in Boonville to scatter their ashes.

Hence the title. Thomas is literally hauling ashes to Boonville. As a gimmick in and of itself, it’s not unique. We all know or know of someone who did it or whose last request it was. But this is the only example I can think of where it has been the gimmick of an around the world jaunt.

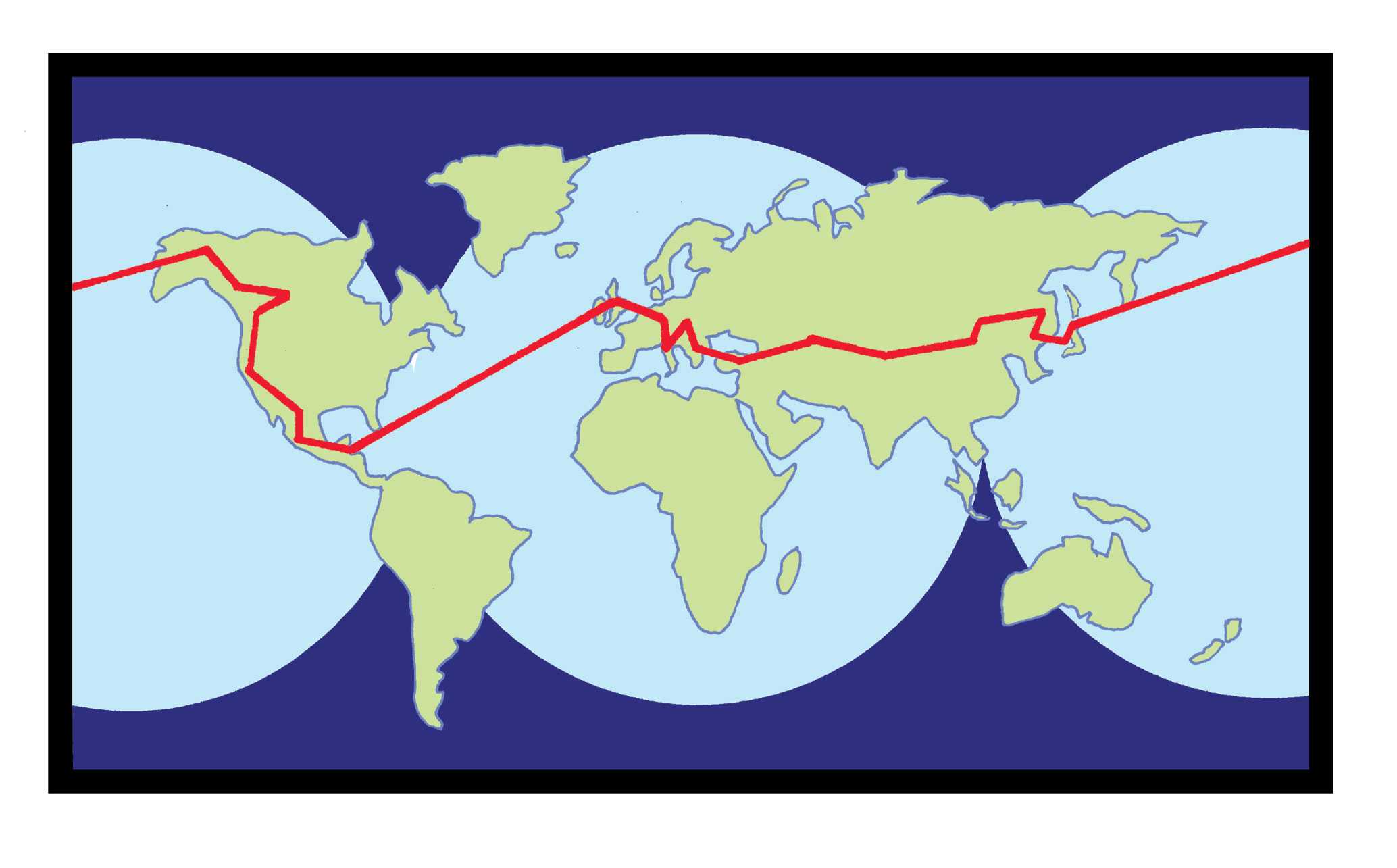

Thomas worked out a route, not only going to places his parents would want to go to one last time, but also one that he describes as “Ride east and avoid wars (p.40)”, a premise I like. It goes primarily across Russia, but also includes a stop in Istanbul, where his parents were hoping to go before his father’s death, and a ride down the Pacific Coast Highway, a route his mother felt his father would have liked.

Thomas rounds up the usual around the world suspects to get the trip going. In addition, he also contacts Adam, an old friend from GP adventures, who has read widely, though not deeply, in motorcycle adventure travel literature. Adam quickly attaches himself to the venture. Adam is described as six foot eight in boots (p.52). I presume that’s five foot nineteen in bare feet.

Thomas double sealed his parents’ ashes in waterproof documents cases because ashes could be banned in several countries as “agricultural products”. With a budget of approximately £20 a day, Thomas dubbed the trip with the punny title of “Poor Circulation”. They left from the Ace, with The Rider’s Digest and its various contributors and friends there to see them off.

Adam and Thomas visit Puke because of its “evocative” name (who wouldn’t?) as well as an eerie, long-deserted campsite in Bulgaria. Because Adam wasn’t comfortable with the idea of riding in Istanbul, Thomas abandons his plan to take his parents there and the two travelers detour to Gallipoli, where Thomas notes that British losses were greater than the Australian and New Zealand loses combined.

Their border crossings were marked by as much by hilarity as hassles. There was a Monty Pythonesque exchange of snappy salutes at the Albanian border, which Thomas credits to his military surplus waterproofs. He also bribed guards with autographed copies of The Rider’s Digest with articles about his trip, even posing for pictures.

He got propositioned by a heterosexual couple he met in the gents, tried out being a taxi-bike driver in Bangkok, and arrived in the US in time for the financial crisis and presidential elections of 2008. Once on the Pacific Coast, he notes its connection to Robert Pirsig and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance as well as discovering that Simon lives nearby.

With the exception of the underdeveloped adventure as a taxi-bike driver, there are no real set pieces here. Crossing Russia is as close as it gets. Russia fascinates Thomas with its mix of incipient dictatorship and laissez-faire capitalist economy; helpful gangsters and bribe-hungry police; floor grannies and window taxes. He found the people warm and open, was impressed by the wide support for Vladimir Putin, and saw a rosy future for the country. Six years later and what is known among many in here New York as the neo-Nazi Olympics, the future no longer seems quite that bright.

Overall, Thomas is more the reporter than the novelist. He states more often than he evokes. The reader understands more often than the reader feels. As a reporter, the telling quote, quirk, or anecdote somehow eludes him, sometimes out of discretion than, say, lack of talent or experience.

Comparing accident scars with a taxi-bike driver is a funny idea (p.331). One more line with examples of each man’s scars would have nailed it.

Giya Balkvadze, a character right out of John Gilbey’s tall tales of martial arts and martial artists, is barely more than half a page (p.170). What were the years he was a chess champion? What are the eight martial arts he mastered? And even for a talented polyglot who started early, mastering 20 languages would be quite a feat. What were they? Thomas leaves all that unanswered.

A hundred pages later, Adam and Thomas meet Alexander, the classic mysterious stranger. Here the reader does get a sense of what Alexander and the conversation must have been like, but a few quotes would have helped flesh it out. To be fair, the point of that section is really Adam’s experience with a small wayside chapel, which is overall more detailed.

Thomas does better with Tevfik, a Turkish motorcyclist he meets in Biga, and Ruslan, a Russian wheeler-dealer who may be a gangster Thomas meets in Volgograd. In keeping an explicit promise Thomas made to Tevfik (who later was killed in a motorcycle accident) Thomas betrays the implicit promise he makes to his readers. He should name the marque of the Old Man of the Souk’s vintage motorcycle. It’s the wrong audience to cheat on that detail. As for Ruslan, if Ashes were a movie, Ruslan would be the lovable, larger-than-life rogue part that lets an actor steal every scene he’s in.

Thomas’s reticence becomes particularly problematic when he writes about his traveling companion. To say that they did not get along could be the understatement of the sub-genre. For most motorcycle adventure travel writers, the plot (or spine or through-line) is the route of the trip. Thomas had potential richer material to work with.

The problems with Adam begin when Thomas suddenly discovers Adam is a racist. Thomas refuses to quote what Adam actually said, so the reader has to take Thomas’s word for it. Thomas does later seem to provide the quote, which is probably a case of bad copyediting, and not bad faith.

Thomas certainly provides basic reportage about Adam’s difficulties negotiating The Other, whether people or customs. Odd for someone who has read a large number of motorcycle travel books. Adam is “paranoid” about using foreign ATMs and listening devices in Russian hotel rooms. He finds the call to prayer a “fucking racket” and the closer social distance in the Middle East uncomfortable. He doesn’t understand that outside Western Europe and Anglophone North America, commerce runs on cash, not credit cards. He even has difficulty riding with his fair share of their equipment. Thomas has to diddle the loads to accommodate Adam’s lack of skill.

I don’t question Thomas’s conclusion that Adam is a racist, even if something about the initial incident doesn’t quite ring true. His racism doesn’t seem to be the real problem. Adam comes across as rather young, immature for his age, and more than a bit of a spoilt brat, going passive-aggressive when things don’t go his way. Adam undermines Thomas’s wish to have a photo of his riding his one millionth mile and refuses to visit a place a few yards away, seemingly just because Thomas felt Adam should see it. At one point, they almost come to blows, but Thomas typically doesn’t give the reader the reason why.

Thomas mostly left such issues out of the blog he kept at the time and is almost as reticent in the book. The reader is provided just enough information to get the idea, but not enough to get interested in the outcome, even though the friction informs and deforms the trip. By not telling the full story, Thomas is not just cheating his readers, but also cheating himself of that book that would read more like a novel that he claimed he wanted to achieve.

To be fair, the casual reader may not be that disturbed by his tendency not to be specific enough when he writes about people, places, and things. His style is very readable. It becomes more of an impediment when he discusses ideas. His observations about the difference between a terrorist and a freedom fighter is trite, but at least short. His observations about Gallipoli are the sort of platitudes that politicians orate on Remembrance Day. To be fair, Thomas is actually sincere.

It seems Thomas has a taste for “dark tourism”, visiting places which are known for dark or evil moments in history. In addition to Gallipoli, he visits Stalingrad (now Volgograd), and claims to have visited Dresden and Coventry, all scenes of massive military casualties. I wouldn’t be surprised if he visited Auschwitz or the Killing Fields at one time or another as well.

There is something about Thomas that reminds me a bit of George Selwyn, a now all-but-forgotten figure in English politics. A member of the Hellfire Club, Selwyn was well known for this taste for the macabre and the necrophilic. He traveled far and wide to attend every execution in general and hanging in particular he could. When this came to the attention of the French authorities, one asked Selwyn if his interest was professional. “No, monsieur”, Selwyn replied, “I do not have that honor”.

There is something interesting going on inside Thomas – probably not necrophilia – that goes unexplored and might have been more compelling than the predictable pablum he produced. He is very focused on trying to keep things light and positive, which seems to be a hallmark of Simon’s circle of Jupiter’s Travelers. Thomas’s dark side might have made for more riveting reading.

As usual with self-published books, the copyediting and proofreading leave something to be desired. It is amazing how many writers will spend money on their trips and on publishing their adventures, but won’t spend even a penny on a professional copyeditor.

Professional assistance might have helped here. Thomas is bedeviled by apostrophes. He consistently misses the apostrophe in The Rider’s Digest, remarkable considering he writes for it. Mark’s needs an apostrophe it doesn’t get (p.61), but eyes gets an apostrophe it doesn’t need (p.114). He reaches the apogee of apostrophe catastrophe on page 138 where he manages to get it wrong four times and right two times, all in three lines and one sentence. That density of error could bring even a casual reader to a complete stop.

Manicom provides an introduction. One of the reasons why Manicom enjoys his position in the motorcycle adventure travel community is that he is under the impression an introduction is supposed to discuss the work being introduced and not his own adventures or the phase of the moon. It’s a bit of a sales pitch – he’s trying to get the browser to buy and read the book – but it’s a welcome sales pitch.

But back to beginnings, which is a larger issue than just Thomas and Ashes. Thomas begins with a bar fight in Bangkok, a scene he doesn’t get back to for some 330 pages (out of a 377-page book). It’s really more of a skirmish and may involve a transvestite, if not a transsexual.

Thomas’s mistake here is one of intelligence. He clearly understands that he has to “hook” the reader in the first chapter. Among us literary types this is called in media res, in the middle of things. It goes back at least as far as The Odyssey, which involved an epic trip of a different sort.

The problem with in media res is that the author has to stop the action at some point and jump back to where the story really starts, to fill in the backstory. In The Odyssey that flashback is somewhere in the middle, if memory serves, which is a bit long to wait, but Homer was dealing with an audience who already knew the basic tale. In other words, the writer has to break the suspense to get everything back on track.

In media res has become an increasingly popular way to start motorcycle adventure travel books. Dr. Pat Garrod (Bareback, issue 165) and Patrick Symmes (Chasing Che, issue 184) both used it, Symmes correctly. As a professional writer, Symmes is aware a reader will only give a book a chapter or two to capture his or her interest. By the end of the first few chapters, Symmes has finished the flashback and the book proceeds in order from there. Gerrold has not one, but two, flashbacks, creating a sense of structural disorganization, despite the rigors of the through-line.

However, hooking the reader isn’t the only thing a beginning does. The beginning also establishes mood, plot, tone, theme, and character: what the story is about. In a travel narrative, the plot is the actual route of the trip, which is why it’s sometimes called the spine or the through-line.

Although Thomas does a good job of establishing his tone – wry and light – he is less successful with the rest. He is not a bar-fight person. He doesn’t even seem to like confrontations, or the situation with Adam would not have reached the point it did. He could even have omitted the bar fight altogether without affecting the whole of Ashes.

Thomas’s book really begins with his being adopted. Ashes may be the only travel book I’ve read that would work with such a Victorian/Dickensian start (helped by his wry tone). If he insisted on beginning with fisticuffs, then his almost coming to blows with Adam would have been the better choice in terms of both hooking the audience and generating suspense. In this type of travel narrative, the travelling companions usually get along well enough. An exception would intrigue audiences. But that’s the story Thomas really doesn’t want to tell.

Nevertheless, Ashes is readable and engaging, a good maiden effort overall. Recommended

.

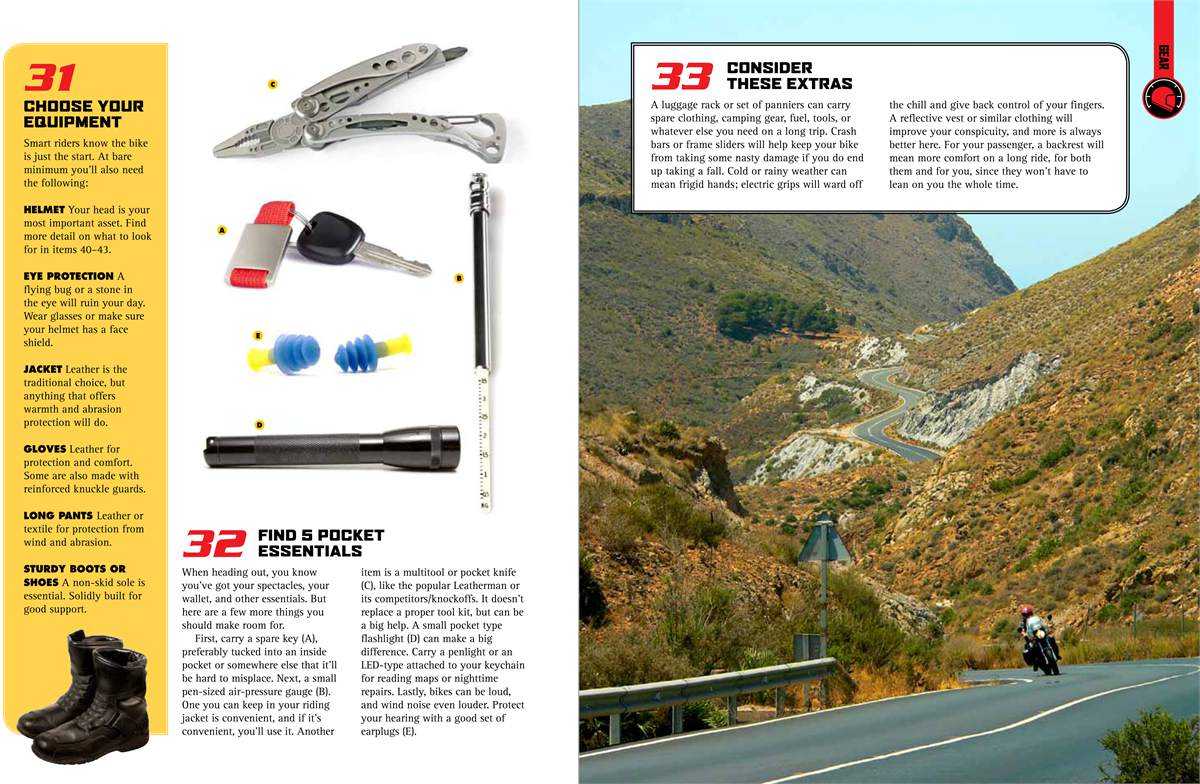

Where to begin is also a question with the next two books, Ace Cafe and The Total Motorcycling Manual: 291 Essential Skills, produced by Cycle World.

Do I begin by mentioning I found both at the AIMExpo in Orlando last October and reprise my joke about the Expo being a motorcycle show without motorcycles?

Or do I begin by noting that Cycle World just celebrated its 50th anniversary and the Ace is celebrating its 75th?

Or do I begin by asking whether the world needs either volume?

Since I’ve already written about the Ace and the books it’s spawned at length (issue 178), let’s start with The Total Motorcycling Manual and its 291 Essential Skills.

The Manual had one of the least professional launches I have ever attended. It was mumbled and disorganized, focusing more on Cycle World’s international distribution network than the actual book itself. (I hadn’t noticed that Cycle World’s previous owners lacked an international distribution network.)

Instead of discussing any of the book’s essential skills, the presented emphasized that The Manual had a sense of humor as well since it includes sections about “How to date an umbrella girl” or “Tell your wife about a new motorcycle”.

The presenters apologized for not having enough copies to hand out to the press, which is a publicity no-no. To be fair, the press event wasn’t exactly packed and most of those who attended didn’t seem interested in getting one of the few copies available. To avoid artificial suspense: yes, I scored a freebie.

Long before it was acquired by Bonnier last year, Cycle World had been publishing a range of books from collections of columns by Peter Egan or Kevin Cameron to 365 Motorcycles You Must Ride, which is a fun bit of motorcycle porn that is best taken lightly, if not with a grain of salt.

It would be a shame if Egan and Cameron were allowed to slip out of print simply because Bonnier wants to tout Cycle World’s new look and focus. Regardless, the first book under the new regime is a lot better than the pitch indicated.

The book is divided into three broad categories: Gear; Riding; and Repair. There are ten breaks called Inside Lines, each one focusing on a different famous race or event: not only Daytona and the Isle of Man, but also Jerez and Nurburgring, among others.

The details of the 291 skills or topics are kept to a minimum. Most are checklists or bullet points and usually take up just a page. Some are only half a page and a few are double-page spreads. There are lots of pictures, both photos and diagrams.

It’s painfully apparent the target audience is ADD-riddled twenty-something males with an interest in racing and sports bikes, even though the thought of someone with ADD riding a motorcycle is chilling to say the least. That potential rider/consumer would also be based in North America, making Cycle World’s emphasis on international distribution all the more curious.

Among the essential skills The Manual offers are how to commute safely (p.102) and split lanes (p.100); how to understand stopping distance (p.164) and how to make an emergency stop (p.165); and how to ride over bridges (p.196) and railroad tracks (p.198).

Some of the essential skills require caveats and qualifications. I’m not sure how to equip your shop (p.223) is a skill, though the section is a good summary of the topic. Here in New York it would be about the size of a studio or one-bedroom apartment and would cost about as much: the upper six figures.

Others are redundant. Both 37 and 40 address proper safety gear. Skill 41 – how to dress like a squid – is not only one of the too many attempts at humor, but also repeats 37 and 40 implicitly.

Usually the humor is kept to the subject titles. Don’t Go Unplugged (p.50) covers ear plugs; Pick A Lock (p.108), choosing a lock; or Go Both Ways (p.21), dual-sports. The essential skill there is understanding what a dual-sport is or does.

Useful might be a better term than essential for some of the topics. These skills might be essential, but not specific to motorcycling, such as how to tie four essential knots (p.129). I learned those – and more – rowing. And of the five pocket essentials, three are typical of what most people who like to be handy and prepared carry anyway – a flashlight, a pocket tool kit, and extra keys – and one – ear plugs – is subject to local legislation.

Then there are some skills that are neither essential nor useful, but are at least interesting, or fun to know. How to pop a wheelie (p.151) is certainly neither, but it’s doubtful there is a rider out there, male or female, who hasn’t tried or wants to try to pop one. There is more to the wheelie than Freudiana. How to kickstart a bike (p.243) hasn’t been an essential skill in decades and is only a useful skill for those riders with a taste for vintage motorcycles and a desire to become retro rocketeers. Still, good to know.

Some skills are too specialized to be essential, though they are useful within one or another sub-group of the riding sub-culture. How to box a motorcycle (p.287), pack for a long trip (p.188), or ride the world (p.204) are not essential skills. While it is nice that Simon got a free plug (as well as Helge Pedersen), an around the world trip is what mastering essential skills lets a rider do, it’s not an essential skill in or of itself. Much the same can be said for a list of ten top rides (p.202) and recommendations to ride across Africa or down the Pacific Coast Highway.

Then there are skills that are strange, and of limited use. I admit that how to be a two-wheeled chef (p.195) – using the heat generated by a motorcycle to cook a meal – was a hoot to read. The likelihood of my ever having to use that knowledge is somewhat limited as is eating road kill (p.194) and carrying a live pig (p.206). How to ride a tight rope (p.187) and how to ride the globe of death (p.170) are even further out there.

Sections on motorcycles in film, music, and books (p.76-78) don’t involve skills, let alone essential ones. Worse, they are not even that well thought through. Of the eight ‘essential’ books, only one – Keith Code’s Twist of the Wrist – is essential. Simon and Pirsig certainly belong on every motorcyclist’s bookshelf, but neither is essential for riding motorcycles. And while Hans Kemp’s Bikes of Burden has a cult following (which includes Manicom and me), it’s a delightful photo essay of over-packed motorcycles in Southeast Asia, where bikes are work horses, not show horses. Again, not essential.

Worse are the skills inserted for comic relief, which are neither useful nor funny. The humor is crude and the attitude is condescending. How to date an umbrella girl (ask someone out on a date) or how to tell a significant other about a new motorcycle (come out of the closet) are interpersonal skills, not riding skills. To be fair, as such, they are essential.

Ben Spies provided a brief introduction, which, as usual, is more about the celebrity than the topic at hand. Though, as someone who reviews motorcycle adventure travel books, I did find Spies’ passing comment, “When I retire from racing I’ll…buy…a cruiser and take a long trip… That’s something I’ve never done, and always wanted to” intriguing.

A racing champion taking the slow way round could make for interesting reading.

Approximately half the skills here are or can be argued are essential: 146 of them, say. Another 87 are useful or at least interesting. A substantial 20% are absurd or meant to be funny. To be fair, perhaps the humor is funny to the late adolescent or college age male I presume is the target audience.

But those 146 sections are rather good as either an introduction to the topic for a beginner or a quick refresher for the more experienced rider. On that basis, Recommended.

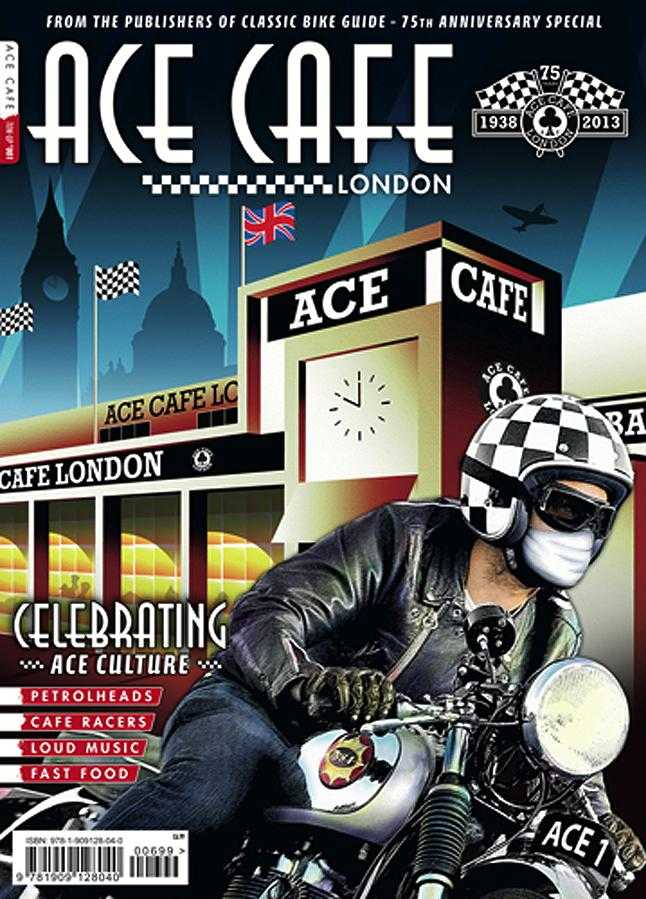

Ace Cafe is a magazine-sized paperback created by our friends at Classic Bike Guide to commemorate the Ace’s 75th anniversary. It’s a good match. Nostalgia and continuity are the stock and trade as much for Classic Bike as it is for the Ace.

According to the copy on the cover, the volume is a celebration of Ace culture: Petrolheads; Cafe Racers; Loud Music; and Fast Food. It’s a rare case of truth in advertising. The actual contents include Ace worldwide; Ace team and events; Ace history and veterans; and Ace style, bikes, cars, and merchandise. Even special Ace custom motorcycles, including a cooperative venture with Mark Upham who has revived Brough Superior. Of course, Mark Wilsmore is interviewed, but so is the Ace’s all but silent partner, George Tsuchnikas.

Most of the material here has been covered before. What is new is Classic Bike’s focus on the future of the Ace. A branch will open in Orlando in the summer, by which time plans for a branch in Germany will be announced. Also in the works are Aces in China, Japan, and Finland. Whether the Ace can sustain its charm and authenticity in the face of such expansion is a question for another time and another place.

Ace Cafe is well done. It’s an example of how a commemorative volume should be, but seldom is. But readers familiar with Classic Bike already know about its level of professionalism.

The book is best for those who want to know something about the Ace, but haven’t read any of the earlier histories, and for completists. It supplements, but does not replace, Mick Duckworth’s Ace Times. Recommended

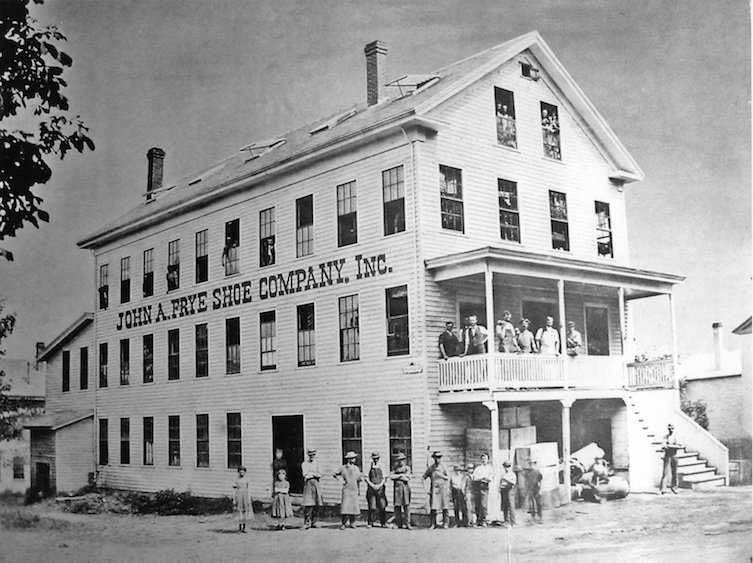

However, I do know where to start with Frye: The Boots That Made History: 150 Years of Craftsmanship; with the question of heritage brands in general and the relationship of Frye to motorcycling in particular.

Frye, the book, is a coffee table book. Coffee table books are known for the quality of the photography and the art direction, not the quality of the research or the writing. Frye, the company, is a heritage brand. A heritage brand is a company whose product or service is known for status and quality for generations.

Other examples of American heritage brands include Brooks Brothers, which will celebrate its bicentennial in four years; Levi’s (Levi Strauss), which is at least a decade older than Frye; and Stetson, which won’t reach its sesquicentennial until next year.

In terms of motorcycling, there’s Schott, which just celebrated its centennial (issue 182), but it is not as old as the very British Lewis Leathers, founded some 22 years earlier. And it’s not only clothing. Both Triumph and Harley-Davidson are heritage brands, or perhaps marques, having been around for more than a hundred years each. But even BMW, a mere baby at 90, could be considered a heritage brand at this point.

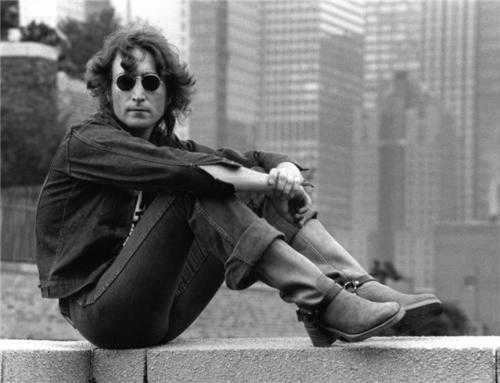

Frye, the boots, holds a special place in the hearts of baby boomers in general and baby boomer bikers in particular. The Times referred to Fryes as the boots of that generation. The book even includes a well-known photograph of John Lennon wearing Frye harness boots (originally designed in 1938). A shot of the classic harness boot also adorns the cover of Frye.

Frye was also one of the brands of choice for many motorcyclists of that period. While the counter-culture tended toward the harness boots, bikers were split between that and the engineer’s boot. (Self-disclosure: between 17 and 27, I wore my Frye harness boots almost every day.)

No one expects the unvarnished truth from this sort of company history. But such histories can be informative – Ace Cafe, for example – or even fun to read – Schott. Here there is little more than implicit and explicit celebrity endorsements and a little too much bombastic flag-waving about Frye’s tradition of patriotism. People interested in the Frye company would literally learn more from Wikipedia’s brief slug.

Nice to know that Frye once produced a line of logo Hopalong Cassidy boots for children or that Jacqueline Kennedy was one of its clients for bespoke riding boots. It might have been nicer to know who created Frye’s double F logo and why.

Also nice to know Frye developed its Wellington/Jet boots for the military or that the Frye family once endowed a library. How patriotic! What good citizenship! But Frye ceased to be a family company shortly after the Second World War, nor does it seem to have maintained its ‘tradition’ of military contracts.

Not mentioned in the book is that the John A. Frye Company has been bought and sold by a series of holding companies since the turn of turn of the millennium. Right now (early 2014) it’s owned by Li and Fung, a $20 billion corporation based in Hong Kong. Li and Fung is best known for accusations of paying its workers minimum wage (if that much) and of unsafe working conditions in factories across Asia. It seems Frye boots have not been manufactured in the US for at least a generation, if not longer.

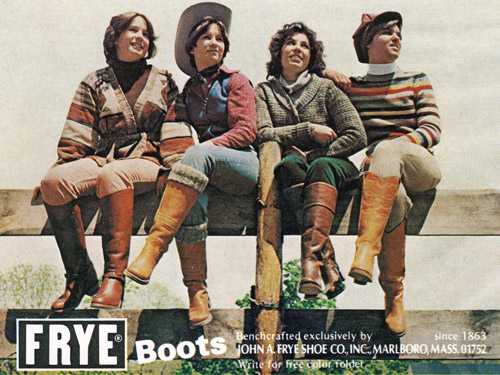

I always enjoy vintage ads and archival photographs and here the book shines. It’s the best part. One entertaining ad filed with period charm is a near pornographic shot of a model in boots and short shorts bending over a bike that I think I remember for the wrong reasons.

The contemporary photography is less memorable. In addition to the expected – and appropriate – product shots of boots, boots, and more boots, there are lifestyle shots of the sort found in medium-quality mail-order catalogues, far below the usual standards for Vogue, say, or even Rizzoli, the publisher, an imprint known for the lush quality of the photography in its coffee table books.

The fashion shots feature celebrities or generically pretty models wearing Fryes. The models are mostly female, which probably accurately reflects Frye’s target market, even though personally I think of Frye as a man’s boot. When I was a young person, a woman in Fryes was vaguely transgressive, if not erotic.

Frye’s connection to riding is acknowledged, but in passing. One shot features two androgynous waifs flanking a low-capacity motorcycle. Another features boot-clad babes, wearing little else, riding pillion on cruisers, the bikers’ Fryes providing more protection than their puddingbowls. The section devoted to work and engineer’s boots includes a whole sentence dedicated to Frye’s connection to motorcycling.

As for celebrities, there are such actors and musicians as Sheryl Crow, Jeff Tweedy, Paul Wesley, and Sam Worthington, among others, usually identified by name in the minimalist captions. Oddly actor Alex Pettyfer is not. His credit is in the back of the book as a model.

Some performers are featured and provide pull quotes or brief essays. Here’s Brad Paisley posing with guitar and Frye boots; there’s James Taylor, cutely winding up his quote with, “You wake up in the morning and see them waiting by the bed, it feels like you’ve got a friend”.

The last section of the book highlights Frye’s limited edition products that were designed to be its 150th year salute to the American flag. As designs, the products are undistinguished. A stars-and-strips motif is etched into the leather, barely noticeable to the casual observer. It lacks, say, the vulgar verve of a Nudie Cohn design.

To a degree, that product line is the point of the book. Patriotism is as much the last refuge of the shill as it is of the scoundrel. However some brands put their companies where their corporate mouths are. People may question the quality of Harley-Davidson’s motorcycles, but not the quality of its American bona fides.

The bikes are manufactured in the United States by union members who work for a living wage that even allows them something of a life. They are in a way The Motor Company’s ideal and its target market. That is something to admire. Unintentionally, with its empty blast of rah-rah-rah-sis-boom-bah patriotism, Frye pissed on my fond memories of my younger self and his favorite brown Frye boots.

There are more interesting ways to burn $75, including one involving a matchbook. What is baffling is trying to figure out who is the intended audience for Frye. It’s not informative enough for libraries. It’s not pretty enough for fashionistas. It’s not enough about boots and motorcycling (or horses) for riders. Not recommended

Jonathan Boorstein