Book Review – Books and Bikesploitation

Before we begin to ride, we imagine ourselves riding: in the dirt; to a far off place; as fast as we can; or even just across town. Perhaps it started with the look or a particular marque; the scent of danger and duende or the lure of the unknown and the open road. Perhaps it was someone we knew: a neighbor or a relative; or a book we read: Robert Pirsig, say, or Hunter S. Thompson. It may even have been a display of vintage motorcycles at a provincial museum somewhere, or, for some, a vision of a tight black leather romper on a blazing red hot Ducati.

These images, these imaginings, came from somewhere. For most of us, they came in part or in total from the movies. And not even good movies. The images usually come from bikesploitation flicks. “The biker is a creation of popular culture,” writes Bill Osgerby in Biker Truth and Myth: How the Original Cowboy of the Road Became the Easy Rider of the Silver Screen (The Lyons Press, 2005), “a glamorized product of movies, magazines, and pulp fiction.”

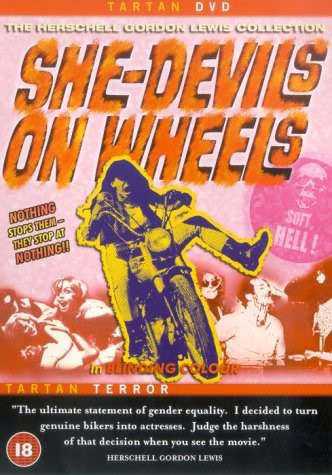

Herschell Gordon Lewis, a film-maker known as the “Godfather of Gore” for such early splatter movies as Blood Feast (1963) and A Taste of Blood (1967) as well as the bikesploitation classic, She-Devils on Wheels (1967), the first biker film with a female outlaw gang, suggested that such exploitation films allow viewers without experience to have the experience without danger and to allow viewers with experience to relive that experience safely. In this case, it is the experience of the outlaw biker.

“This image of the motorcyclist as somehow a social outsider (who socializes with other outsiders) is an international post-Second World War phenomenon,” Steven E. Alford and Suzanne Ferriss comment in Motorcycle (Reaktion Books, 2007). Noting that “the image becomes commodified and marketed” and quoting Suzanne MacDonald-Walker about the “gentrification of rebellion”, Alford and Ferriss come close to David Brooks’ concept of the bobo.

Brooks coined the term for his millennium book, Bobos In Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There (Simon & Schuster). Brooks, a right-wing populist intellectual, defines bobos as bourgeois bohemians, rich baby boomers, whose mix of counter-culture consumerism now dominates global culture. He sees the semiotic co-option of the counter-culture by the mainstream marketplace as a good thing, unlike, say, Alford and Ferriss, who emphasize that “the counter culture placed the motorcycle at the centre of both its definition and critiques of freedom at home and abroad”.

Or, as Melissa Holbrook Pierson says in Motorcycle Mania: The Biker Book (Universe Publishing, 1998), “The thing about these stereotypes – by definition “oversimplified opinions, affective attitudes, or uncritical judgments” – is that they only exist for those who are witless enough actually to believe that these biker exploitation flicks … tell some essential truth about people who like to ride motorcycles”. In short, we get the hairy outlaw biker gang stereotype in the movies because that outlaw biker remains easy to market to those who can afford to buy tickets to the cinema.

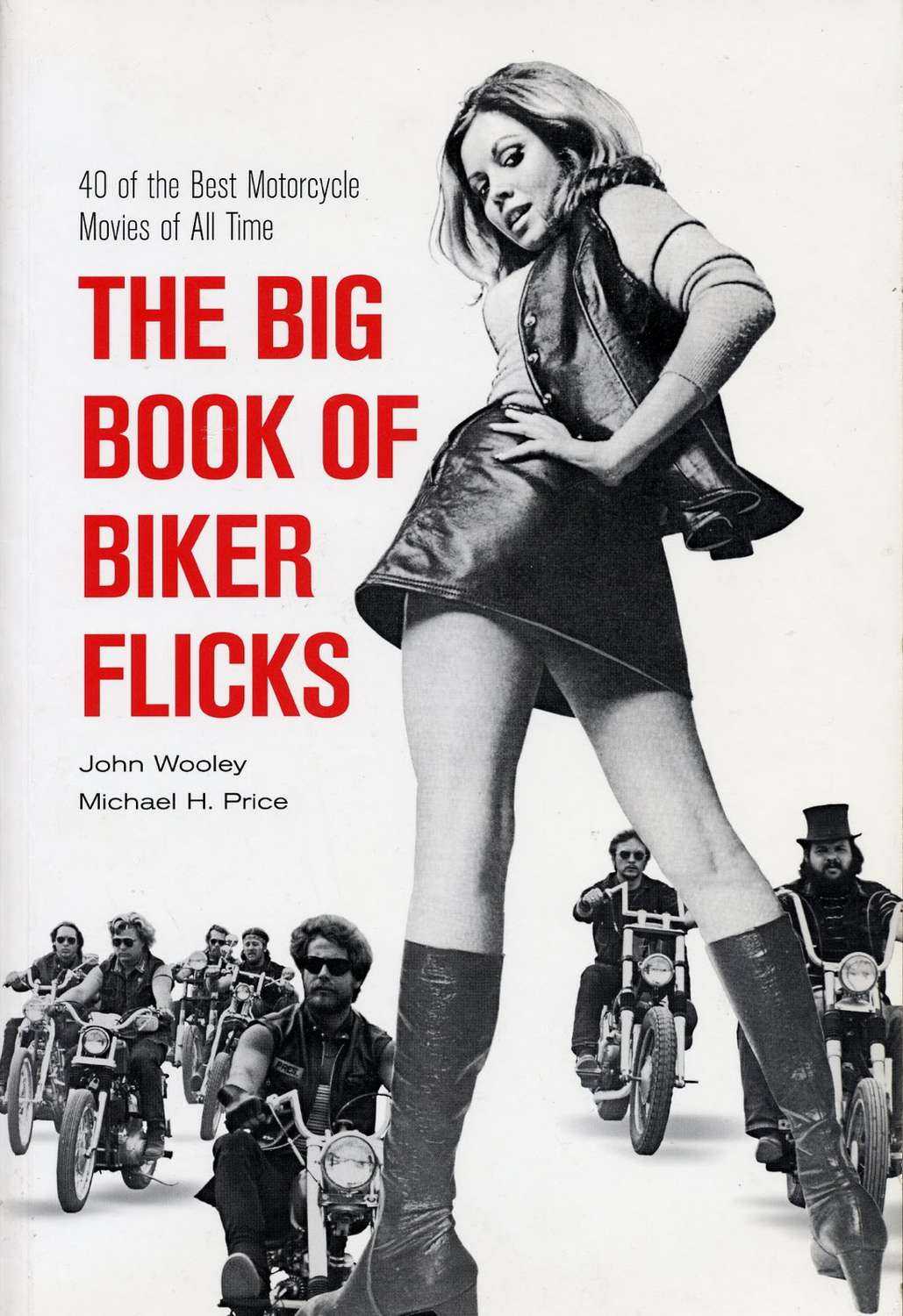

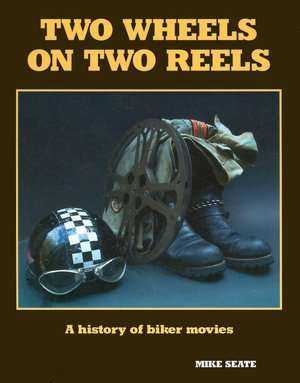

The authors of this month’s books are actually on a run in search of bikesploitation films. Riding a rig is Mike Seate, who wrote Two Wheels on Two Reels (Whitehorse Press, 2000). Jammed into the sidecar are the double-bill of John Wooley and Michael H. Price, authors of The Big Book of Biker Flicks (Hawk Publishing, 2005), who don’t ride. On pillion is an empty duffle bag to be filled as soon as Seate gets the rig to the nearest DVD store.

Waving at Seate as he rides by are Alford, Ferriss, Osgerby, and Matthew Drutt, editor of Motorcycle Mania, all in traditional pitch-black, pitch-perfect Schott, Barbour, Langlitz, or Lewis Leathers jackets. Over Alford and Ferriss’ leathers are academic gowns. The caps are securely attached to the tops of their pudding bowls. They are card-carrying, if not charter, members of The International Journal of Motorcycle Studies. Yes, analyzing how and what motorcycles, motorcyclists, and motorcycling mean is now fodder for academic social and cultural historians.

Brooks, meanwhile, is waiting for his bespoke riding suit to be run up by Lewis while his personally customized Harley-Davidson is shipped from Orange County Choppers. Only Paul Teutul Sr. will do. Brooks, the self-confessed bobo that he is, is born to be mild: uh: wild: born to be wild: he was born to be: wild. Herschell Gordon Lewis, however, prefers to toot down the road in a vintage Morgan trike.

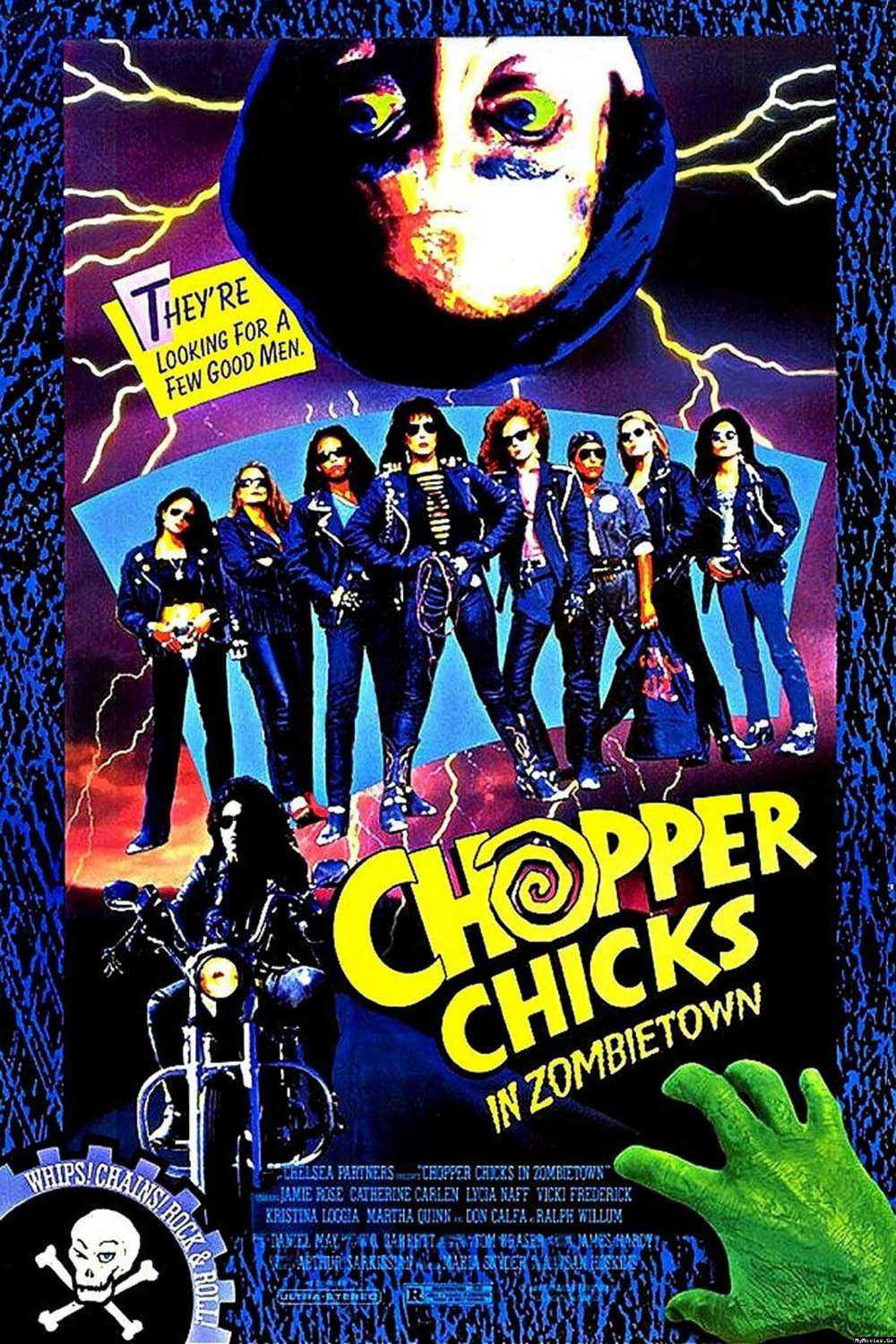

Of the two books actually being reviewed this time out, Seate’s is the better. This is fortunate. Seate is also editor and publisher of Café Racer for which The Rider’s Digest contributing writer Linda Wilsmore is a regular columnist. That’s not six degrees of Kevin Bacon. That’s incest. He also likes the same line from Chopper Chicks in Zombietown (1989) that I like, which counts for something.

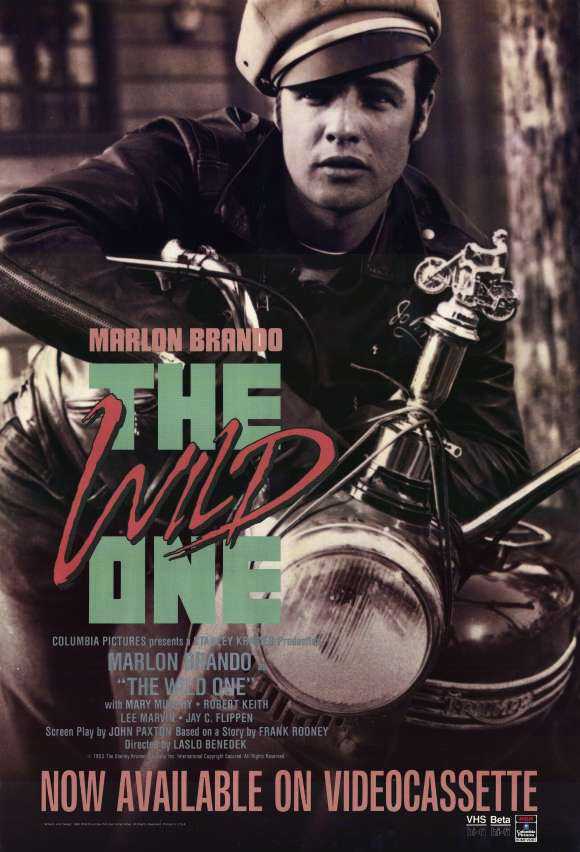

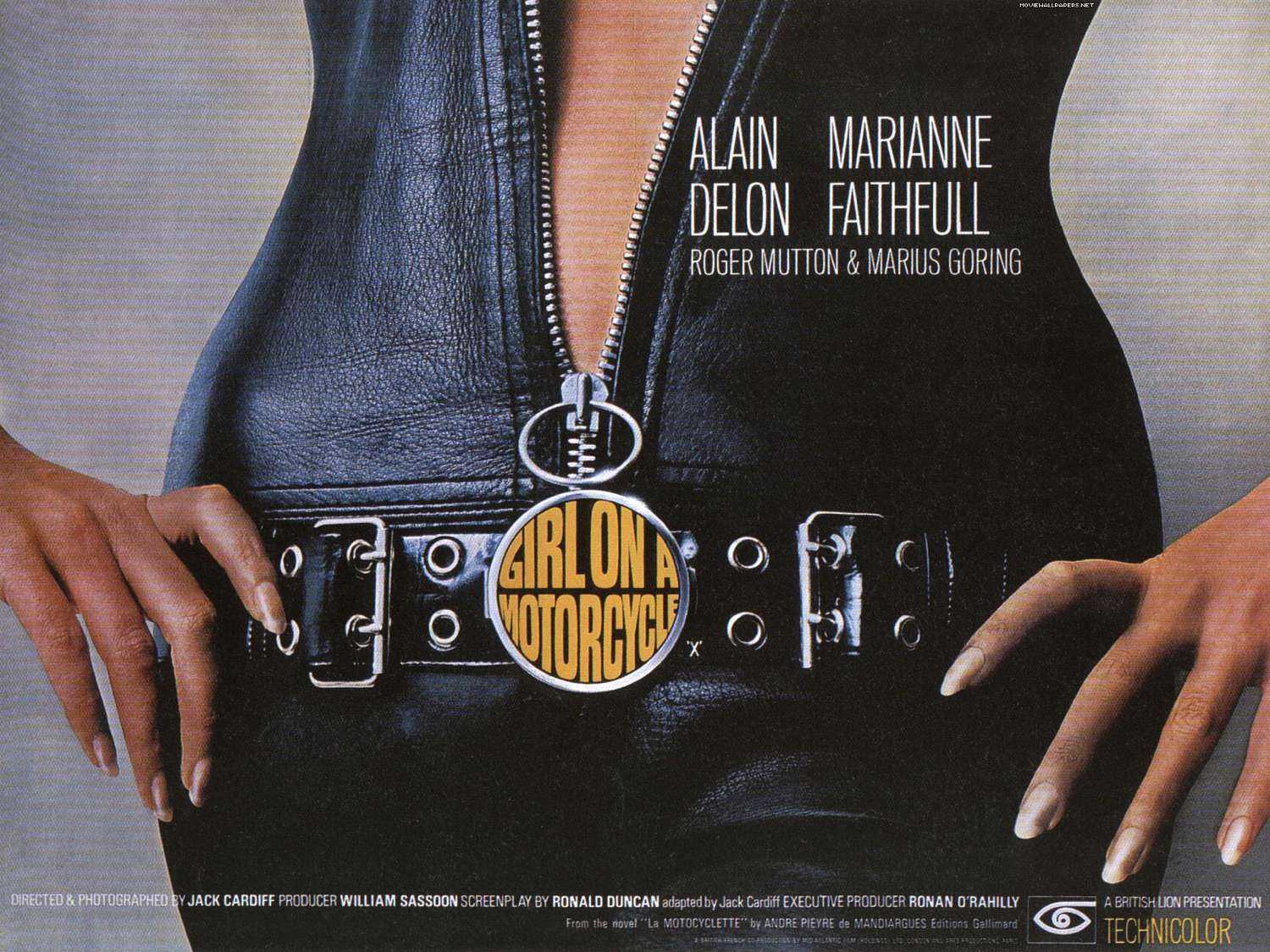

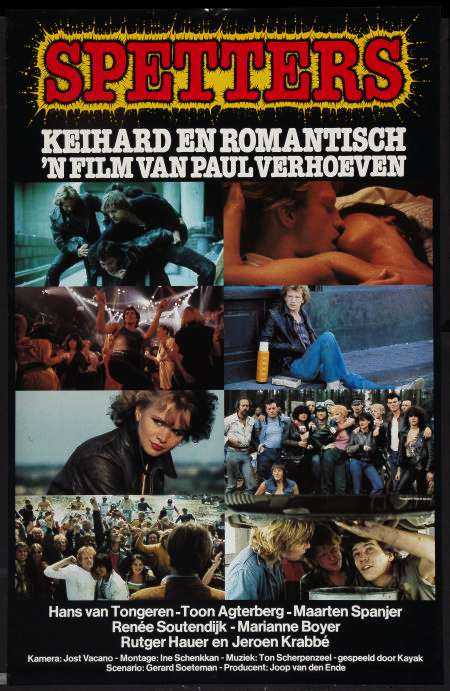

Two Wheels on Two Reels covers movies with motorcycles from the beginning, but the emphasis is the 50-year period following the release of The Wild One in 1954. The bulk of the films discussed are English-language, with the occasional foray into such important foreign language releases as Spetters (1980) or Girl on a Motorcycle (1968).

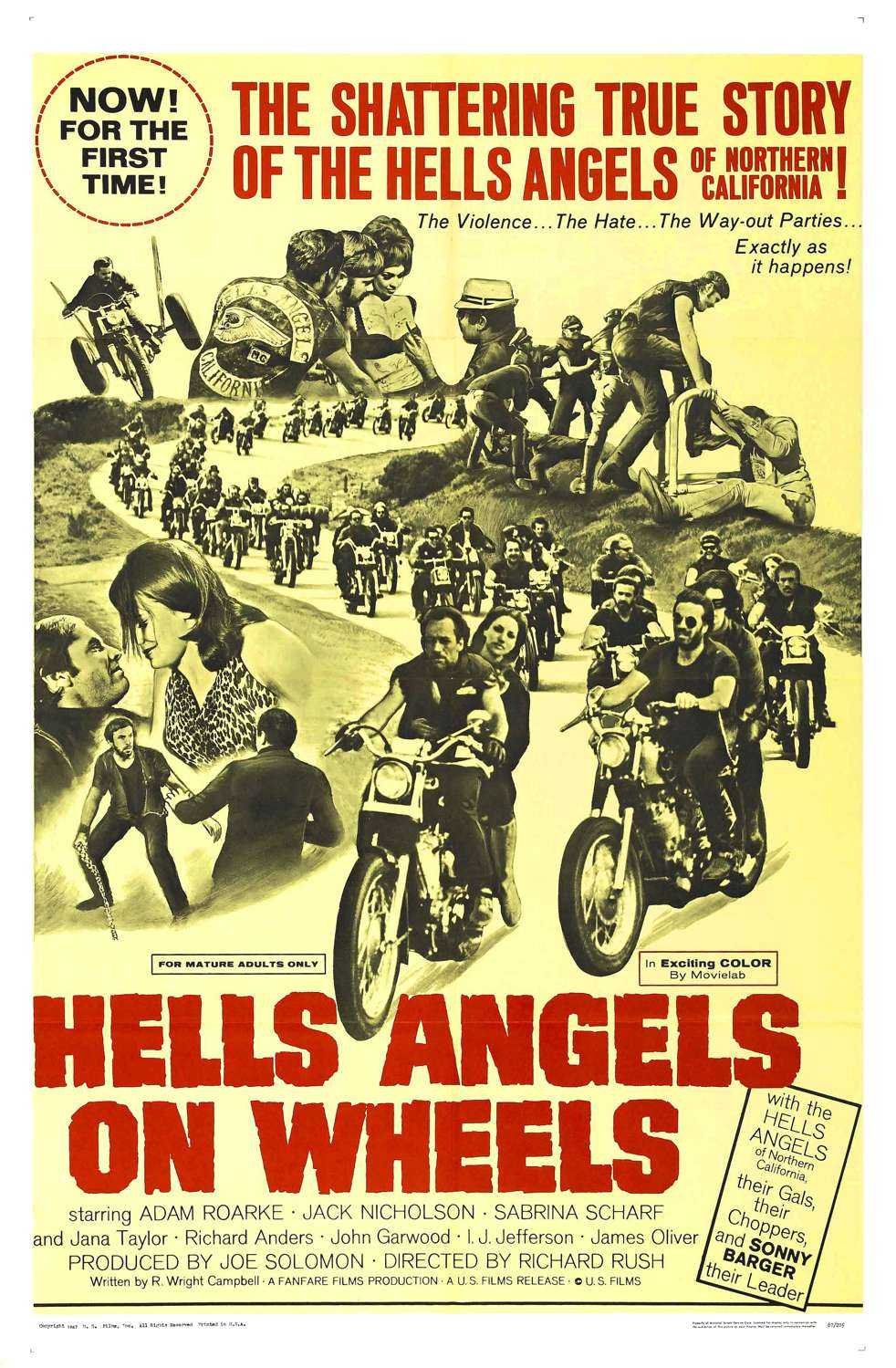

Seate keeps things light, breezy, and moving. He cracks wise about bikesploitation clichés and genre conventions. He comments about Hell’s Angels on Wheels (1967) that it “displays a rare commodity in early biker movies: a plot”.

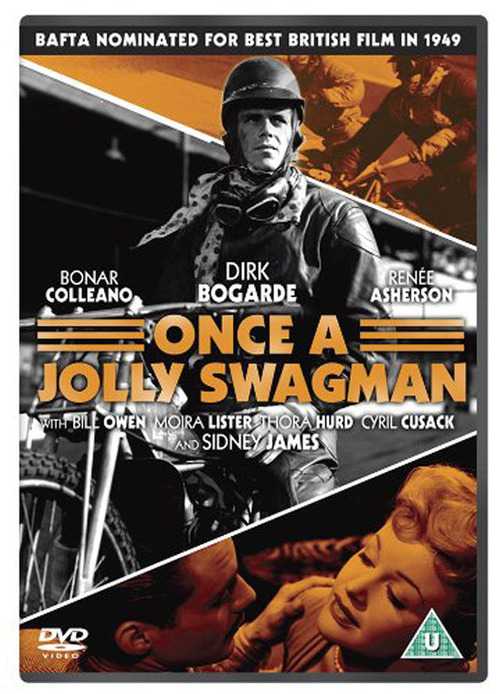

He points out that British films about motorcyclists have greater awareness of social and economic influences. Even in such movies about racing as No Limit (1935), Once a Jolly Swagman (1949), and Silver Dream Racer (1980), the differences between the lives of the privateers and the factory racers are more than just acknowledged.

Seate even attempts to put biker cinema in the wider cultural and political context of the times each film was released. “What makes Psychomania such a product of the times and so different from the previous British biker movies was the lack of social conscience,” he writes about the 1971 cross genre film in which an outlaw gang called The Living Dead are actually turned into zombies.

On the negative side, Seate sacrifices depth for readability. As a result some of his critical conclusions seem more arbitrary than reasoned. On the other hand, he does have critical conclusions and the reader gets both the sense and the details of the arc bikesploitation films have traveled over the half-century covered in Two Wheels on Two Reels.

It’s not the contrived contrast it should be to say that Seate looks at biker cinema from the motorcyclist’s point of view, while Wooley and Price look at biker cinema from the movie buff’s point of view. Specializing in books about the horror genre, they know a thing or two about exploitation films. For them, the heyday of the bikesploitation film was the late sixties to early seventies. The 40 films they cover were produced for the grindhouse and the drive-in. The earliest, of course, is The Wild One and the last is Road of Death (1974).

Each film gets its own chapter. There’s a plot summary, production details, critical reception, and a sense of whether a particular movie is good, bad, or indifferent. Usually it’s the second. Most include quotes from the major figures involved, some from interviews Wooley and Price conducted, some found through researching various archives. They reject any attempt or approach to see the genre in larger terms. “We’re hardly here to hold a grad-student seminar on philosophy,” they explain in the introduction, adding that if biker movies had a philosophical backbone, it would be dumbed-down existentialism. It is doubtful that Sartre and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance will hit the best-seller lists any time soon.

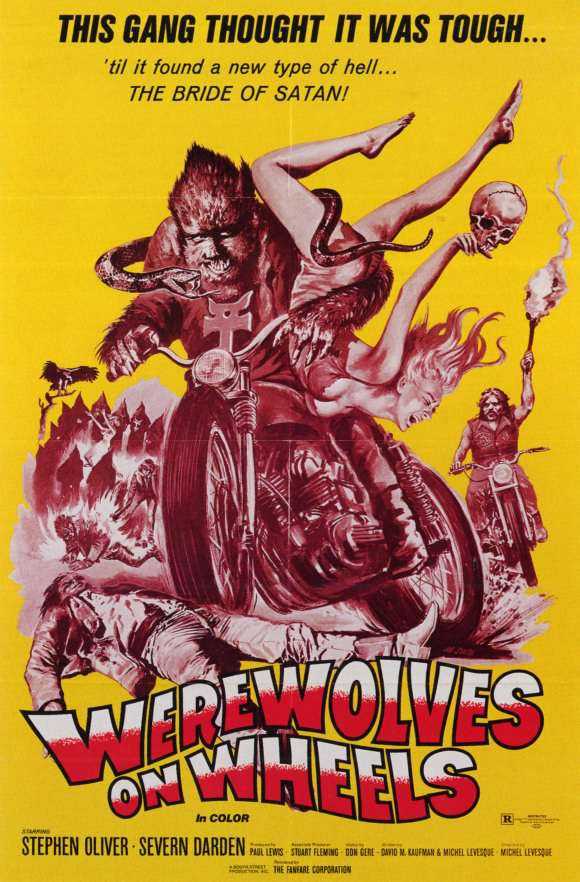

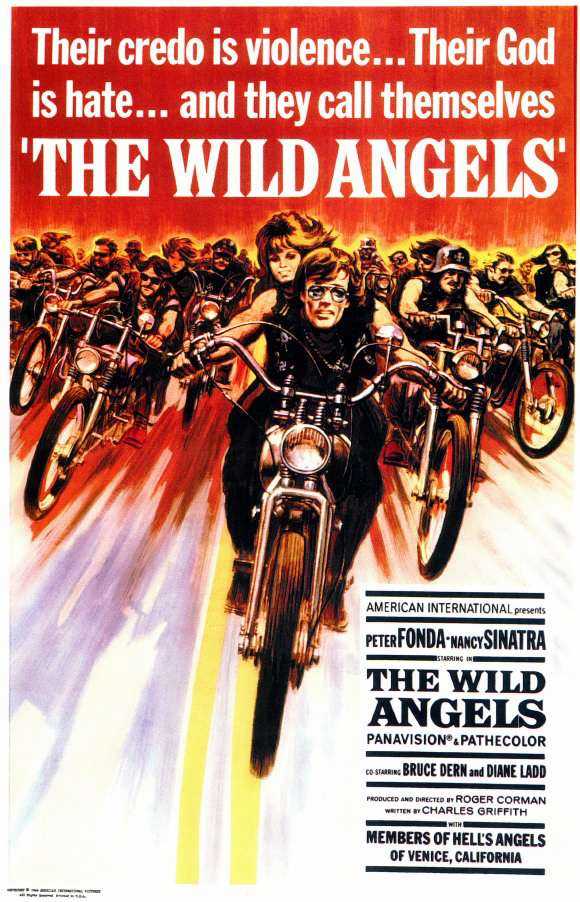

Like Seate, Wooley and Price focus on films that have motorcycles in them, excluding films that only have memorable motorcycle moments, whether scenes or images. The selection includes films we’ve heard of – The Wild Angels (1966) – films we wish we had – Hell’s Angels ’69 (1969) – and films we wish we hadn’t – Werewolves on Wheels (1971).

Entries include fun facts and trivia. Russ Meyer’s Motor Psycho was produced and released the same year (1965) as his cult classic, Faster, Pussycat. Kill! Kill! Both share much of the same cast and premise, including “the incredible” Haji, a cult figure in her own right, and the idea of a trio of vehicular thrill-seekers who cross the line. The Savage Seven (1968) not only was produced by Dick Clark, but also featured a theme song called Anyone for Tennis by a group named Cream.

It’s great fun, especially when Wooley and Price get to the cross-genre releases at the end of the bikesploitation era. In addition to Werewolves on Wheels, there’s The Black Angels (1970) – blacksploitation as well as bikesploitation – blikesploitation? – and Pink Angels (1972) – gay bikers racing to get to a drag ball, complete with a then fashionable, but absurdly gratuitous, downbeat ending.

On the downside, each film gets a chapter that is so self-contained that the book reads like an anthology of related articles rather than a cohesive volume building to a point or larger cultural or cinematic issue, despite frequent references to the overall arc of the genre.

As for the genre itself, both books jeer at the repetitive tropes that return and return in biker films. Yet, the pleasures of genre in general are of new variations on old themes. Whether we call such genre expectations clichés or conventions, we laugh at them when we see them and miss them when we don’t.

In terms of biker movies, the first genre experience is that motorcycles have to be central to the film. A memorable image or a great set-piece is not enough. The nude rider in Vanishing Point (1971) is certainly a memorable image, perhaps even iconic, but it could be edited out of the film without damaging the film. Just as iconic, but only a bit more integral to the goings-on are Pamela Anderson in Barb Wire (1996) or Arnold Schwarzenegger in the Terminator series (1984, 1991, and 2003) or even the fascist chic look of the biker adversaries in the Dirty Harry good rogue cop vigilante versus the bad rogue cop vigilantes outing Magnum Force (1973).

Quentin Tarantino frequently uses motorcycles as an iconic nod to the grindhouse cinema that inspires his work (Kill Bill (2003, 2004), et al.). Lewis doesn’t even think Ghost Rider (2007) qualifies as a genre entry, since the use of the bike is iconic. “The motorcycle is just a mode of transportation,” he told me in a recent interview.

Queer cinema, of course, has long used the biker iconographically. The mysterious motorcyclists astride their Indians accompanying the eerie, elegant, and enigmatic Princess in Jean Cocteau’s Orphée (1950) are fraught with ambiguous sexual tension and implication. By the time his protégé, Kenneth Anger, creates Scorpio Rising (1964), the imagery is completely homoerotic.

Andy Warhol’s subsequent Bike Boy (1967), the biker as icon is deconstructed with a rather long portrait of a rider whose sexuality and working class background are ridiculed by the usual round-up of Warhol “superstars”, although the biker himself seems clueless as to what’s really going on. It comes off as a mean-spirited take on the archetype, leaving it void of any real meaning beyond drag and dress-up.

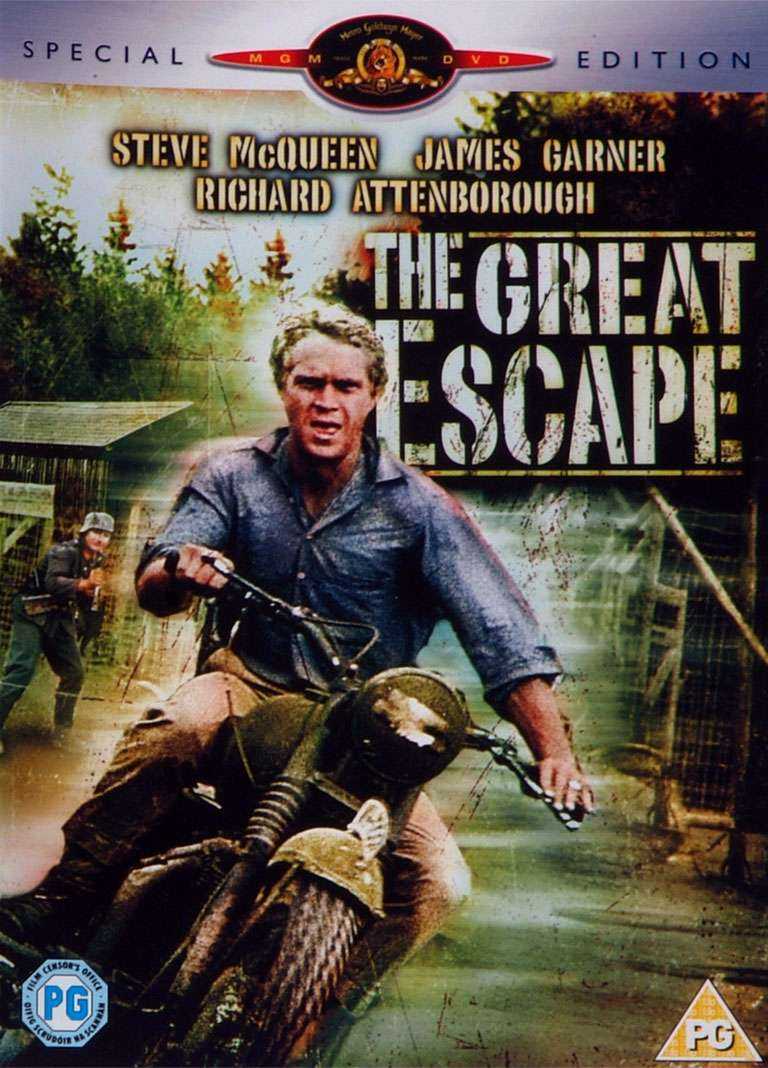

And however thrilling the motorcycling is in The Great Escape (1963), in the end it’s a war movie with a great chase sequence, not a biker flick. While James Bond and Tom Cruise films include motorcycles chases – Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) and Mission Impossible II (2000) are good examples of each respectively – by no stretch of the imagination are they about motorcycles or motorcyclists. My favorite is the seventeen-minute motorcycle chase in Matrix Reloaded (2003), in which Trinity (Carrie-Ann Moss) races into traffic as well as faces the usual stunts and dangers of a high speed chase.

Parenthetically, the motorcycle’s first appearances in the movies explored the potential for speed and peril, including such silents as Mack Sennett’s 1915 Love, Speed and Thrills, a slapstick comedy that involves a love triangle and the Keystone Kops as well as a horse and an abduction. And all in one reel. More interesting are the use of motorcycles in Harold Lloyd’s Girl Shy (1922) or Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. (1924), in which serious students of the cinema inform us the motorcycles are metaphors for the heroes’ unruly passions.

If motorcycles are central to the film, and not just icons and sequences, it will also have such iconic elements as black leather jackets, unkempt bikers, custom choppers, rowdy behavior due only in part to drink or drugs, dangerous street racing just for the thrills, unmotivated chases and crashes, and shared or taken women.

Third, despite the biker as a counter-culture icon, the values and politics in bikesploitation films tend to be conservative, if not reactionary, and the heroes’ working class. As for other possibilities, Alford and Ferris note that “Although the leather-clad prole may have become an iconic image, a wide variety of other images exists of both the motorcycle and the motorcyclist, for both have protean significance in popular culture.” Squids, lone wolves, and RUBs (Rich Urban Bikers) have certainly appeared, but none as yet have really taken hold.

It’s not absolutely clear whether the scruffy, but well-groomed, hero of Torque (2004) is actually a squid, but he’s definitely not a member of a biker gang: they’re the bad guys. Detractors refer to this movie as either Dorque or Fast and Furious on two wheels. It is certainly aimed at the same audience demographic. It is also possible that Torque was meant to be funny.

The lone wolf alternative has fared better and has been around longer. Then Came Bronson (1969), which was a pilot for a short-lived TV series in the States, is probably the best known example. The series permanently warped the minds of an untold number of pubescent and pre-pubescent male baby boomers when it came out. With the premise of a career drop-out, the titular Bronson, who rides the Pacific Coast highway to find himself, the pilot had theatrical release in Europe. Only a few episodes dealt with motorcyclists or motorcycling. For the most part, the show was Route 66 on two wheels. Bronson retains cult status here and comes the closest to how many American bikers who are not club or gang members see themselves.

Wild Hogs (2007), a male menopause comedy, features RUBs going mano-a-mano against a real biker gang. Or is that bike-o-a-bike-o? Nevertheless, it was a popular success. Despite such alternative models being available, and at worst, not unsuccessful, don’t expect any follow-up odd couple comedies of biker and RUB any time soon.

Fourth, plots are seldom more than premises for the riding and fighting sequences. This bikesploitation flick might be about a gang on a rampage: Motorcycle Gang (1957), say, or Devil’s Angels (1967). That film has an outlaw gang fighting outlaws even more unsavory than the gang: Born Losers (1969), which introduced Billy Jack to an unsuspecting public, or Angels Die Hard (1970). And then there are movies with undercover cops who infiltrate outlaw gangs for one reason or another. In Beyond the Law (1993) it’s to get the evidence against the gang who are arms dealers; in Stone (1974), it’s to find out who is killing the gang members one by one. Stone, an Australian entry, is better known for its fond portrait of the local bikie scene than it is for the TV episode of the week plot.

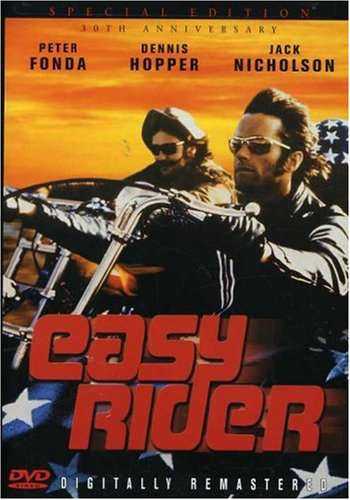

No article about motorcycle movies would be complete without a list of bikesploitation flicks of its own. And there is that empty duffle bag on pillion to fill. Let’s start with five essential classics: The Wild One, The Leather Boys (1964), The Wild Angels (1966), Easy Rider (1969), and Quadrophenia (1979). Aside from being iconic biker flicks, these films moved beyond exploitation and gave more than a nod to issues of rebellion and class identity in a manner that was less romantic and more realistic than usual.

If that selection seems a bit bald or bold, it can easily be filled out or shored up with another handful: Girl on a Motorcycle (released in the US as Naked Under Leather), She-Devils on Wheels, Silver Dream Racer, Spetters, and Eat the Peach (1986). Here the genre is stretched with solid releases. The once erotic, now camp Girl on a Motorcycle plays fast and loose with Freudian implications. She-Devils is exploitation cinema at its best. Auteur Lewis even gets his gore on with a grisly finale. The remaining three focus on other motorcycle sub-cultures. They are as much about the protagonist pursuing his or her dreams as it is about motorcycles.

It’s not a stretch then to add such other approaches to the biker icon as Once a Jolly Swagman (1963), The Damned (1963), The Born Losers (2004), Motorcycle Diaries (2004), and The World’s Fastest Indian (2005). Swagman is of course the classic about speedway racing and union organizing. The Damned, with its weird mix of biker and sci-fi tropes, has a political lunacy all its own as well as an outlaw biker gang leader wearing a tweed jacket and carrying a rolled umbrella. Motorcycle Diaries and World’s Fastest Indian are biopics of Che Guevara’s political coming of age and Burt Munro’s achieving a record at Bonneville Flats respectively.

Since there is still a bit of room in that duffle bag, let’s add some perverse choices: rarities or oddities that frequently slip under everyone’s radar. Chopper Chicks in Zombietown is about a female biker gang, the Cycle Sluts, who ride into town to pick up some men, but find, well, zombies. There are undoubtedly some female readers who will point out that that is a difference without a distinction. At some point in this bikesploitation flick the leader of the pack tries to rally her gang members by saying, “You women are Sluts. Try to act like it.”

The Loveless (1982) is as much art house cinema as biker flick. Directed by Kathryn Bigelow (The Hurt Locker), tone and mood trump plot and character in what is an elegiac view of the lives of bikers and greasers in the 1950s. The tag line for the film – Muscles Clad in Black Leather – makes it sound like something it’s not.

Knightriders (1981) is a one-off change of pace outing for George “Night of the Living Dead” Romero. Here the biker gang is a troop of Renaissance Faire re-enactors who joust on motorcycles instead of horses. The story itself is a casual, gentle update of some of the Arthurian cycle, dealing with issues of chivalry and camaraderie.

Little Fauss and Big Halsy (1970) features Robert Redford in his Downhill Racer athlete as rotter mode, in this case an ambitious motorcycle racer who is as untalented as he is unscrupulous. Michael J. Pollard plays the more talented racer/mechanic Little Fauss. The story is about his maturation as a person and a racer. Nevertheless, Redford gets to sleep with the girl, while Pollard gets to sleep with the motorcycle.

Roustabout (1964) is the only film in which Elvis Presley gets to ride a motorcycle. He was a Harley man, but here he gets to ride a Honda, presumably to assure mid-60s audiences that Presley was among the nicest people you’d meet on one. This being an Elvis Presley film, not only does he get to ride the Honda, he gets to sing while riding the Honda. The title of the song is Wheels on my Heels.

Most of the books and DVDs mentioned are available through Amazon.uk.

Jonathan Boorstein

jonathanb@theridersdigest.co.uk