Book Review – Of Tarmac and Tourists

A young African-American in leathers snaps a photograph of his KTM alongside a Triumph and a Suzuki parked on Jones Street in Greenwich Village. He is probably unaware that he is around the corner from Fourth Street, where positively Bob Dylan once rode his Triumph.

This rider is more than a little reticent about why he takes the picture with his smartphone, even to a kindly-disposed, gently-aging eccentric. But it seems he is on a trip and his souvenirs of having been there are photos of his motorcycle next to other motorbikes he encounters on his travels. No other information is forthcoming.

I rather fancy he is couch surfing his way across the USA, leaving a trail of tweets and Facebook posts in his wake to mark his passage. I suspect that were I years younger and female, I might have learned more.

Such long-distance motorcycle trips are nothing new, of course, but they are becoming increasingly common. Writing about them goes back nearly as far – at least to the eve of World War I, if memory serves – and that too has become more frequent. A handful of such rider-writers have even become repeat offenders. Having published one volume about their two-wheeled adventures, they go off on another trip to publish another book. Nothing like brand extension to boost sales of all the volumes in the series.

Two such repeat offenders are Geoff Hill and Charley Boorman. Hill, a professional reporter and recipient of prestigious journalism awards, has published four motorcycle travel books. Boorman, a professional celebrity and recipient of handsome pay checks, has produced six books and may well have unleashed a seventh upon an unsuspecting universe by the time you read this. Their volumes raise questions of accuracy and authenticity in travel writing.

A good travel book provides adventures without the demands of hardship. It is filled with incidents and characters that are just real and interesting enough to engage your attention without engaging your emotion. The narrator should be a good traveling companion possessing both a sense of humor and an ability to capture the spirit or essence of a place or person in a well-turned phrase or a well-chosen anecdote. The trip itself needs to have something unusual if not unique about it. The situations and set pieces should be real, not stunts staged just to have something to write about.

A great travel book goes one step further: the outward journey reflects an inward journey.

Both writers fall short of the mark. Curiously the stronger writer published the weaker book. Let’s look at Hill first.

Hill’s previous travels include riding from Delhi to Belfast (where he lives and works) on a Royal-Enfield and riding Route 66 on a Harley-Davidson. Neither route is exactly original, but the first also involved carting about a packet of special tea leaves. I presume the second sounds a lot more romantic to readers in the UK who are his intended audience. For Hill, readers from the US would be lagniappe.

As it turns out the gimmick of matching the motorcycle to the trip is secondary as is the trip itself. Hill is a humorist. The trips are the situations for Hill to react in his comic persona: a put-upon Biggles by way of Monty Python and Firesign Theater. In The Road to Gobblers Knob (2007) the trip is to ride the full 16,500 mile length of the Pan-American Highway from Chile to Alaska.

The catch is that the highway is not as clearly defined as its name. Worse in Canada, Mexico, and the United States the parts of the local roads systems that are part of the highway, aren’t designated as part of the highway. The trip starts in Quellón and over the course of the journey settles on Gobblers Knob as the terminus. Let’s face it: “Gobblers Knob” sounds funny; “Deadhorse” doesn’t.

According to Hill, the Pan-American “was the world’s longest road: a road on which travelers faced being baked in deserts, frozen in mountains, kidnapped and murdered by Colombian drug barons, buried under Peruvian avalanches, drowned by the Guatemalan rainy season, fleeced by eight-year-old Ecuadorean border touts, wasted by Montezuma’s revenge, driven mad by black flies in the Yukon, eaten by Alaskan grizzlies and, worst of all, limited to a glass of Chardonnay a day in California”. He neglects to inform us whether it is that it’s only one glass or that the glass is of Chardonnay that makes it the worst.

He could find no books about travelling the Pan-Am, decides to write one, makes the obligatory nasty comments about Boorman and Ewan McGregor’s entourage and sponsorships, and settles down to arrange his own. Why selling out for one to two hundred thousand is more virtuous than selling out for one to two million goes right over my head. Regardless, the premise that there is an inverse relationship between the cost of a trip and its authenticity is false.

He contacts BMW, who is not interested, but leaves the reader with the feeling that the purpose of that request was to make more Boorman/McGregor jokes. For a journalist, Hill seems tone-deaf to what constitutes a stunt, even going as far as praising Richard Halliburton’s legendary stunt of swimming the Panama Canal to pay the lowest toll just to have something to report in a book and on the lecture circuit. Halliburton, something of a forgotten ancestor of today’s adventure travelers, made a lucrative living between the wars with such antics.

Hill goes on to solicit a bike from several other companies. Ultimately, Triumph contributes an appropriate motorbike: a Tiger. Hill finds an appropriate travelling companion: Clifford Patterson. Patterson has an Aprilia. Hill affects being Don Quixote to Patterson’s Sancho Panza. They name their bikes Tony (the Tiger) and April (the Aprilia). The choices are not very original, but probably better than the leaden whimsy of Rocinante and Dapple would have been. With sponsors for transporting the bikes to the bottom of South America set, they are ready to go.

Each country gets a short history. Native groups are virtually enslaved by Spanish colonialists who are overthrown only to have the new governments overthrown by the United States. Chile, for example, is summed up: “Incas… build huge network of palaces, temples, fortresses and roads, then pass the time sacrificing children, supply of llamas having run out… Spanish arrive [and] take over the country… installing feudal system of rich landlords owning vast estates run by virtual slave labour… Virtual slaves… declare war on Spain. Spanish, confused by fact that Chilean revolutionary leader is called Bernardo O’Higgins and is son of Tyrone man, admit defeat… Salvador Allende abolishes feudal estates to make poor wealthier and happier. US Government, which thinks only rich should be happy, gives CIA $8 million to topple Allende government and install General Pinochet, liked only by his mum and Margaret Thatcher… Pinochet forced out. Rest of world discovers Chilean wine.” Presumably little of it is Chardonnay.

Noting the dissolution of the republic of Gran Columbia (which included Panama, Ecuador, and Venezuela as well), Hill writes, “Within ten years, Venezuela and Ecuador sue for divorce, citing… Columbia’s drug habit”. California gets the cryptic “Spanish arrive, but having no credit cards and unable to decide between a double decaff espresso and a frappomochacino with a twist, leave”. The ground zero of coffee culture in the US is Seattle in Washington State. The first cappuccino in the US was served here in New York in 1927. (If it matters, an American glass of wine contains a few more fluid ounces than a European glass and there didn’t seem to be a lack of Chardonnay in the UK at the last gastropub I visited. Admittedly that was eight years ago in Kentish Town.)

All this is breezy, for some amusing, but is also wogs-start-at-Calais humor. There is even a passing reference to “bongo-bongo land”. References to Columbian drug lords, banditos, and revolutionaries stalk the bulk of the book in general, and the first half in particular. The signs and portents abound in just about every encounter in just about every South American country. Hill has even read Two Wheels through Terror, motorcyclist Glen Heggstad’s account of his being kidnapped by a Columbian gang (Heggstad, a black belt, makes his escape and then, incredibly, continues on his trip).

In contrast, Hill’s descriptions of place are lovely, despite the occasional flippancy. “Angelmo, where the air was rich with a strangely appealing blend of fish, honey and cheese. Vermilion wooden buildings teetered over the water, and for a few pesos a fisherman rowed us out around the wooded islands of the bay, each one dotted with extravagantly turreted homes.”

A similar contrast exists when it comes to people. At the beginning of the book, people talk in a faux wooden manner that is supposed to be funny. “As in international sportsman and winner of so many writing awards we’ve had to get the mantelpiece reinforced twice?” asks his wife. “Will Paddy Minne, the world-famous Franco-Belgian motorcycle mechanic, be going with you again?” asks a willing sponsor.

Dialogue loosens up a bit once Hill hits South America. People met along the road however remain bland sketches more often than not and dialogue is more paraphrased than quoted. Once Hill runs low on money and has to request comps from tourist boards up and down the West Coast of the United States, things pick up. He has to justify the freebie. The humorist takes the back seat to the journalist. Now we meet interesting characters who do such things as run motorcycle, vacuum cleaner, and radio and electricity museums. “There’s one great thing about America,” he writes, “it does wonderful little museums.” Despite being on Granville Island, he misses visiting Vancouver’s wonderful little model railroad museum, but perhaps there is more to “wonderful little museum” than being a wonderful little museum that requires it be American as well.

On the other hand, he can’t resist jokes about Americans being supersized aspiring assassins. “Actually, I thought, it’s unfair to criticize some midwestern Americans as obese people who drive obese cars and whose only exercise is shooting each other. Sometimes they go abroad and shoot other people too.”

The handouts however do not reduce the sniping at Boorman and McGregor. While he does have the grace to blush – he notes that Patterson and he have developed a team as devoted to making things work – he doesn’t even get as far as Peter Egan does in a recent article in Cycle World: “If you’re Ewan McGregor or Charley Boorman, you might see a road across Siberia, where you get to pick your big, heavy bike up out of the mud, over and over again. Those two guys should get some kind of medal… just for persistence. Someone once described adventure as “nothing but a badly planned vacation,” and McGregor and Boorman proved that all the planning in the world doesn’t protect you from the realities of weather and distance and human whim.”

Those realities provide the book with its true set piece: Columbia. Hill doesn’t get kidnapped. After all the heavy handed foreshadowing, turns into a giant fizzle, he wipes out, damaging both the bike and himself, which nearly derails the entire trip. He discovers that Columbia is not filled with banditos, revolutionaries, and drug lords, but real people, many of whom go out of their way to help. Which doesn’t stop him about making jokes about those people of Panama.

Border crossings provide minor set pieces – not surprising since American extraterritoriality has made even routine crossings border on the lunatic, the paranoid, and the dystopian. He’s on record as listing being stuck at the Mexican border as one of the worst experiences of his life. On the other hand, crossing the US border was easy. Then again, his papers were in order for the second, but not for the first.

What is missing in all his adventures in the Pan-Am Highway itself. We get a little about it at the beginning, a little at the end, and of course a little at the Darien Gap, the 83 miles in the middle where it’s not. Hill gives no sense of what the Pan-Am did or means to any of the countries it crosses. Why is the route so vague? It’s as much a colonial “royal road” as any the Spanish ever built. Did it succeed in advancing American interests there, or did it rapidly become as forlorn and forgotten as Route 66 or the Lincoln Highway?

The larger liability may be Hill’s relentless flippancy. His constant barrage of jokes gets in the way of enjoying the details of the journey. The trip degenerates into what jokes Hill can make about it. The earlier book, Way to Go, had a better balance of comedy and reportage. Here it’s become what we in the US call “shtick”.

I’ll give Gobblers Knob three out of five wheelies, but it’s really a weaker entry from a writer demonstrably capable of better work.

Boorman does shtick of another sort. If I were doing my shtick about who’s on the saddle and who’s on the pillion, I would say that Charley Boorman is on the saddle, while riding pillion is Charley Boorman. At no time did Boorman as a little boy turn to his father and say, “I want to be an obnoxious effervescent buffoon on television when I grow up”. He probably said a fireman or policeman, or, since the father in question is the eminent film director, John Boorman, perhaps an actor or a cameraman. It’s unlikely a child would want to be someone whose work is as difficult to understand as that of a director, who, as Lee Strasberg often said, makes the events in a play or script possible. On the other hand, Boorman’s professional persona makes the events in his “reality” adventure travel programs possible. It takes a lot of smart to be that dumb, but it also creates a monster that shadows and overshadows its creator.

For those whose memories may be failing or who live 24/7 wearing a full helmet, Boorman and his old friend McGregor decide to take a motorcycle trip together. At that point, Boorman was no one. Within the usual constraints of time and budget as well as personal and professional commitments he could just about go and do what he wanted when he wanted. McGregor wasn’t that lucky. He was already a world-famous actor. He couldn’t and he can’t. Where ever he goes becomes a circus. Their first venture made the best of that and produced the six-part juggernaut that was Long Way Round.

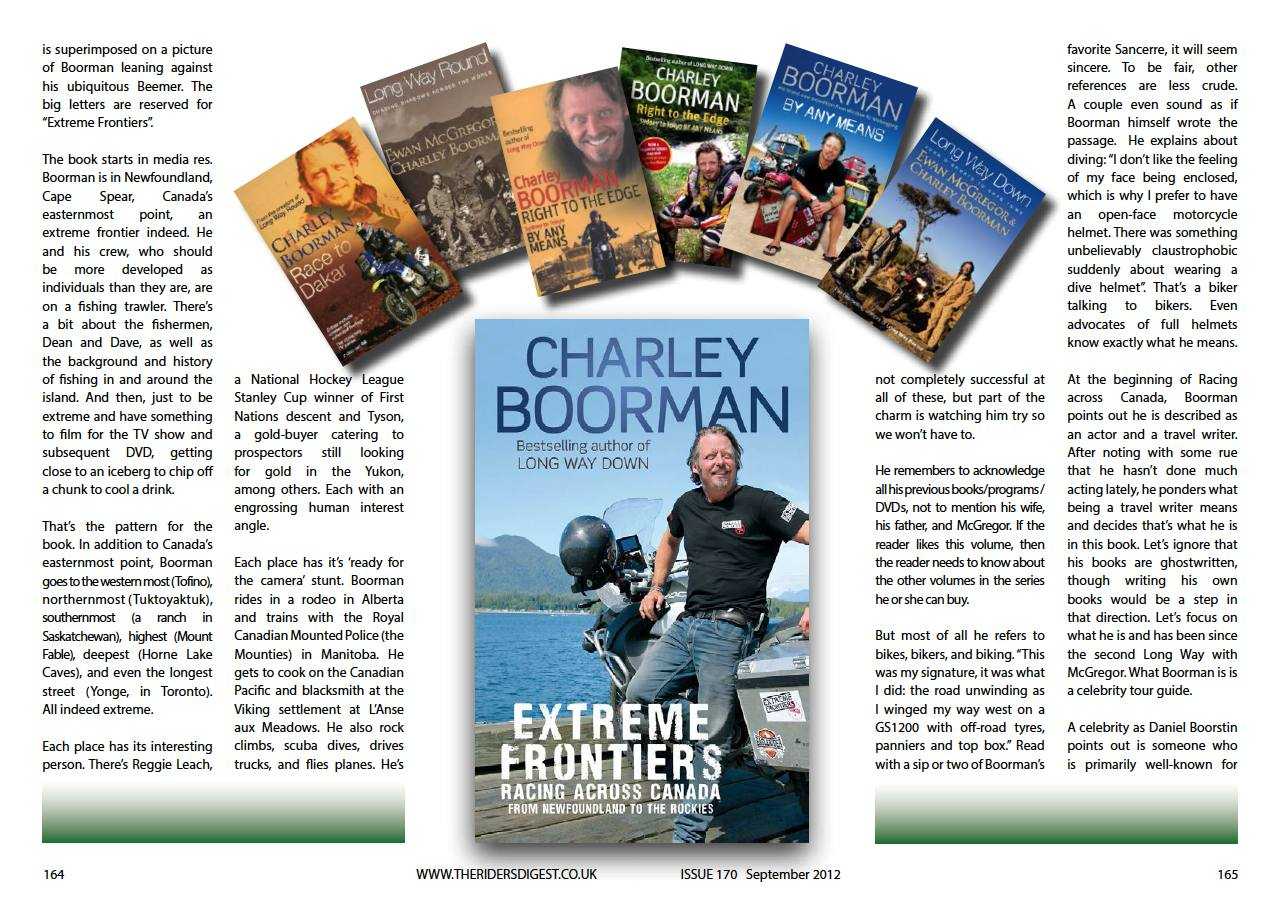

Boorman uses his second-hand fame and turns up next in his first solo outing: Race to Dakar (my favorite, if that matters). After a second round with McGregor – Long Way Down – Boorman goes off on his own with two more series – By Any Means – each featuring his attempts to out Phileas Fogg Phileas Fogg. In addition to his current escapade, Extreme Frontiers: Racing across Canada from Newfoundland to the Rockies (2013), he also conducts motorcycle tours. “Have your own Long Way Down with me next August/Sept 2013 and have the ride of a lifetime from Cape Town to Victoria Falls and onward into east Africa, Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique and SA”, he touts on his website.

As for Extreme Frontiers, Boorman (and his ghostwriter, Jeff Gulvin) says of the seven-week trip, “It was an expedition – we’d be crossing a continent and it would be on bikes and boats and buses – but this was one, single vast country and we’d have enough time to get to know not only the place but the people properly as well”.

There are certainly people aplenty here, and places as well. And things to. Properly is another question. This is one book that can be judged by its cover. The title is superimposed on a picture of Boorman leaning against his ubiquitous Beemer. The big letters are reserved for “Extreme Frontiers”.

The book starts in media res. Boorman is in Newfoundland, Cape Spear, Canada’s easternmost point, an extreme frontier indeed. He and his crew, who should be more developed as individuals than they are, are on a fishing trawler. There’s a bit about the fishermen, Dean and Dave, as well as the background and history of fishing in and around the island. And then, just to be extreme and have something to film for the TV show and subsequent DVD, getting close to an iceberg to chip off a chunk to cool a drink.

That’s the pattern for the book. In addition to Canada’s easternmost point, Boorman goes to the westernmost (Tofino), northernmost (Tuktoyaktuk), southernmost (a ranch in Saskatchewan), highest (Mount Fable), deepest (Horne Lake Caves), and even the longest street (Yonge, in Toronto). All indeed extreme.

Each place has its interesting person. There’s Reggie Leach, a National Hockey League Stanley Cup winner of First Nations descent and Tyson, a gold-buyer catering to prospectors still looking for gold in the Yukon, among others. Each with an engrossing human interest angle.

Each place has it’s ready for the camera stunt. Boorman rides in a rodeo in Alberta and trains with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (the Mounties) in Manitoba. He gets to cook on the Canadian Pacific and blacksmith at the Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows. He also rock climbs, scuba dives, drives trucks, and flies planes. He’s not completely successful at all of these, but part of the charm is watching him try so we won’t have to.

He remembers to acknowledge all his previous books/programs/DVDs, not to mention his wife, his father, and McGregor. If the reader likes this volume, then the reader needs to know about the other volumes in the series he or she can buy.

But most of all he refers to bikes, bikers, and biking. “This was my signature, it was what I did: the road unwinding as I winged my way west on a GS1200 with off-road tyres, panniers and top box.” Read with a sip or two of Boorman’s favorite Sancerre, it will seem sincere. To be fair, other references are less crude. A couple even sound as if Boorman himself wrote the passage. He explains about diving: “I don’t like the feeling of my face being enclosed, which is why I prefer to have an open-face motorcycle helmet. There was something unbelievably claustrophobic suddenly about wearing a dive helmet”. That’s a biker talking to bikers. Even advocates of full helmets know exactly what he means.

At the beginning of Racing across Canada, Boorman points out he is described as an actor and a travel writer. After noting with some rue that he hasn’t done much acting lately, he ponders what being a travel writer means and decides that what he is in this book Let’s ignore that his books are ghostwritten, though writing his own books would be a step in that direction. Let’s focus on what he is and has been since the second Long Way with McGregor. What Boorman is is a celebrity tour guide.

A celebrity as Daniel Boorstin points out is someone who is primarily well-known for being well-known. (Not one of us is related to either of the other two.) A guide is an odd sort of authority, both providing expertise and insulating experience. In this case, Boorman walks the reader through a series of action-packed adventures, all visually stunning, but favoring the action visuals over the other things Canada is and has to offer.

It’s more than adventure travel. There’s the Group of Seven, important Canadian painters from the early 20th century. The McMichael is just outside Toronto where Boorman raced down Yonge Street. There’s the Shaw Festival also in Ontario, which presents more than just George Bernard Shaw. Vancouver’s galleries are filled with contemporary First Nations art and its Museum of Anthropology displays both old and new pieces in a stunning building designed by the noted Canadian architect Arthur Erickson. Vancouver itself is regarded as a model of successful urban planning (though a former mayor suggests that they got it almost right). In short, Boorman presents a very limited and limiting view of Canada. And a rather anti-urban one at that.

Ultimately, Racing across Canada is a cog in Boorman’s well-engineered travel and tourism business. He works with solid professionals to produce solidly professional products. You’ll read it; you’ll enjoy it; and half an hour later you’ll be looking for a book to read. Again, the shtick got in the way. Three out of five wheelies: the book is too well-engineered to be bad, but not bad enough to be good.

Hill’s book is available through Amazon.uk; Boorman’s, wherever mass media is sold.

Jonathan Boorstein

jonathanb@theridersdigest.co.uk