Globe Girdlers Six

Hard to believe, but circling the world on a motorcycle goes back more than a hundred years. It did not start with Ted Simon, despite what many still believe (Simon, incidentally, has never made such a claim).

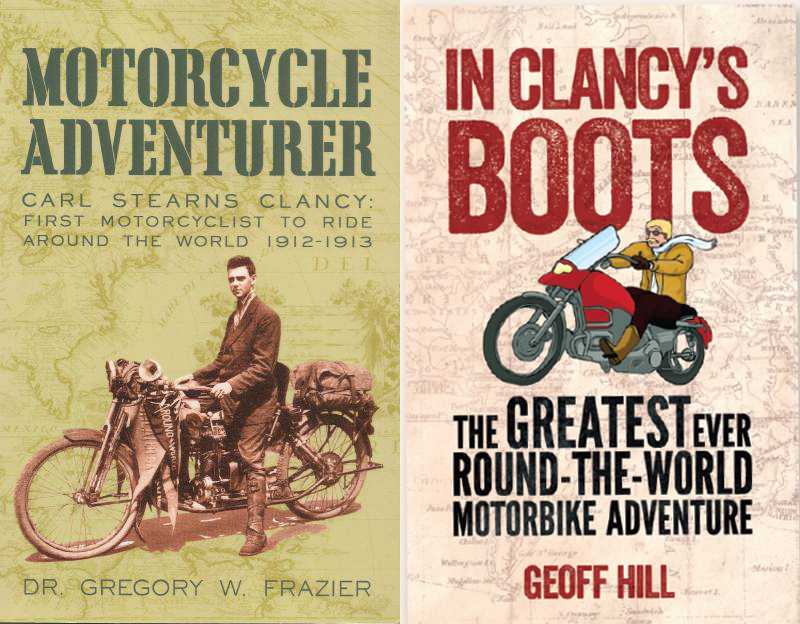

The first was actually Carl Stearns Clancy, an American, who – in a wonderfully horrific Edwardian phrase – “girdled the globe” just before World War One. More than 80 years later, Dr Gregory W. Frazier, himself a five-time globe-girdler, spent 16 years uncovering Clancy’s adventures, which were then recreated by Geoff Hill as a centennial trip. The globe girdlers – Hill and Clancy – were accompanied in one or the other of their respective circumnavigations entirely or in part by Frazier, Gary Walker, Robert Allen, and Walter Storey.

Frazier published his research in Motorcycle Adventurer (2010), with an introduction by Dave Barr, another globe-girdler of some note. Frazier also found Clancy’s rough draft of a follow-up book, titled The Gasoline Tramp, which he edited and published as an e-book. (As editorial policy, The Rider’s Digest does not review e-books, so Gasoline Tramp will only be referred to in passing.) Hill published his recreation of Clancy’s trip in In Clancy’s Boots (2013). An American edition of Hill’s book has been announced for a fall release. If all this were the opening credits of a film, I would add “and special appearances by Liam O’Connor and Richard Henry Schultz”.

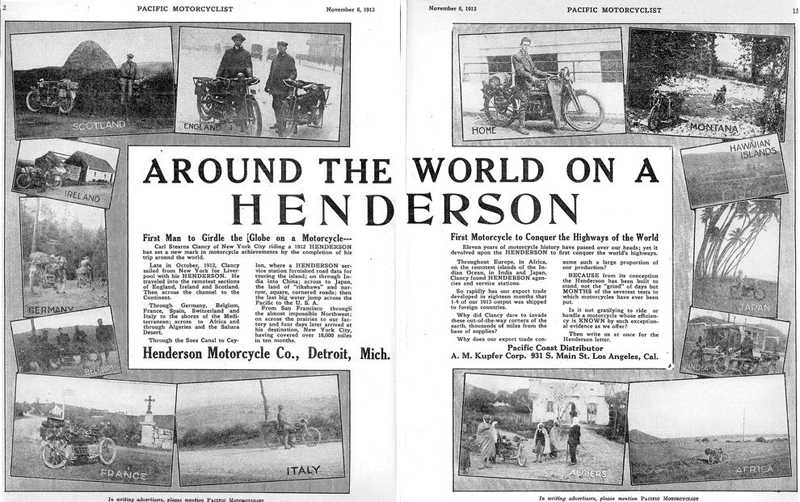

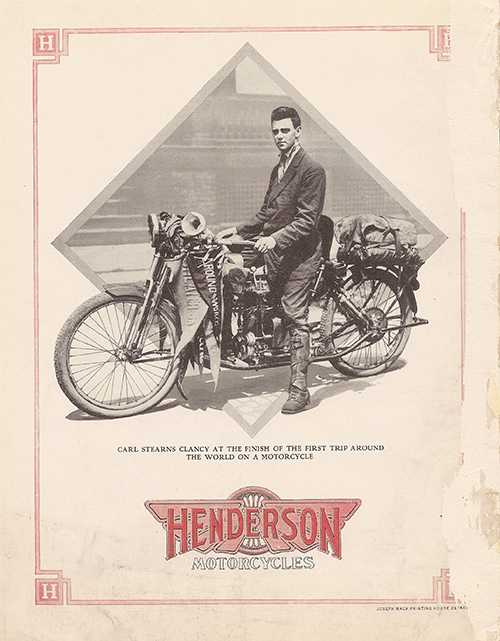

But let’s start at the beginning, with Clancy himself, the very first motorcycle globe-girdler. Clancy (1890 to 1971) was young, in his twenties, when he decided to take a year off from the daily grind of a regular job and see the world on a motorcycle. As befits someone who not only went on to have a long career in film and publicity, but also seems to have been something of the classic “Son of a Preacher Man”, he arranged to fund his trip by writing articles for The Bicycling World and Motorcycle Review and by developing dealerships around the world for the Henderson Motorcycle Company, which also provided the necessary machines.

Clancy establishes his globe-girdling premise in the first paragraph of his first dispatch to The Motorcycle Review: “Old Mother Earth has been circled by almost everything at one time or another. Sailing craft, steamships, railway trains, bicycles, pedestrians and motorcars have all had their turn. Nothing remains but the airship, the submarine and the motorcycle – and now we’re going to give the motorcycle a chance (Frazier p.7)”.

Clancy establishes his globe-girdling premise in the first paragraph of his first dispatch to The Motorcycle Review: “Old Mother Earth has been circled by almost everything at one time or another. Sailing craft, steamships, railway trains, bicycles, pedestrians and motorcars have all had their turn. Nothing remains but the airship, the submarine and the motorcycle – and now we’re going to give the motorcycle a chance (Frazier p.7)”.

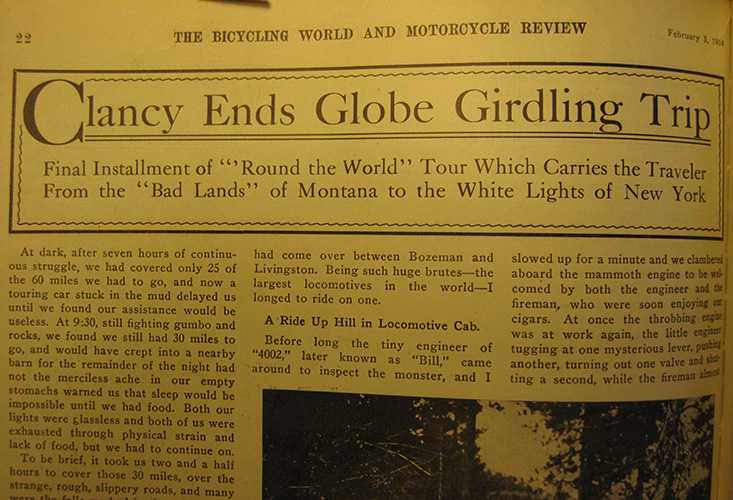

He goes on to say that he will lay out a route for future motorists – whether car or cycle. He ultimately covered 18,000 miles in eleven months, starting in Great Britain (Ireland, Scotland, and England), going through Holland, Belgium, France, Spain, Algeria, Tunisia, Italy, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Malaysia, China, and Japan, before returning to as well as crossing the United States.

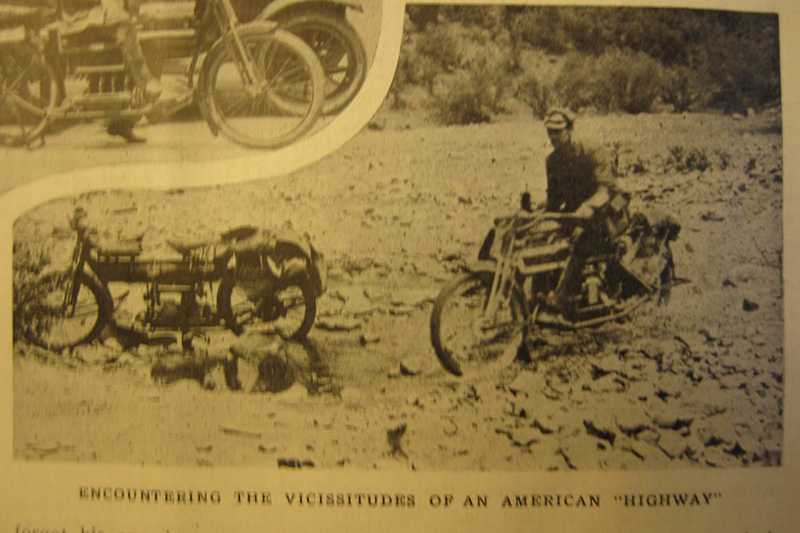

Hill with a certain humor, and not that inaccurately, describes Clancy as having sallied forth armed with only a pistol and a tweed suit. Not to mention a pair of sturdy boots. Clancy – and his travelling companion, Storey – sallied forth with all that and more: “The equipment that we have chosen for the trip – which by the way will cost us at least $4,000 – is merely illustrative of the care we have taken to insure the success of our strenuous journey. First of all, we are to use two four-cylinder Henderson motorcycles, equipped with a 29 by 2¾-inch Goodyear non-skid tires, Persons saddles, Veeder cyclometers, special luggage carriers, full assortment of extra parts, and a complete set of the tools necessary to overhaul the machines en route. Two suits of Nathan’s “Koveralls” are depended upon to protect us from rain and cold. A folding typewriter will help out in preparing our manuscripts, and large fountain pens will be used to take our notes. In addition to the foregoing a fine camera with an anastigmat lens has been added to the equipment, and a medicine kit practically completes the necessities (Frazier pp.10-11)”.

Despite starting out with Storey, Clancy does most of his trip alone. Clancy describes Storey and himself as “enthusiastic motorcyclists (Frazier p.7)”, but by the second installment, Clancy confesses that Storey had never ridden before. When they leave Paris, Storey leaves for New York, while Clancy carries on. It isn’t until Clancy reaches San Francisco that he finds a more suitable riding companion: Allen, who turns up on his own Henderson, a 1913 model. Allen agrees to accompany Clancy as far as Chicago, leaving Clancy to finish the last leg back to New York on his own.

Clancy quickly became an expert not only in finding people to sell Hendersons around the world, but also in finding where there were and where there were not motorcycles. There weren’t many in France, but San Francisco fairly “swarmed” with them (Frazier p.228). He notes Birmingham’s nascent motorcycle industry and visits Henderson’s factory in Detroit. He even manages to be the first motorcycle to cross a Tunisian/Algerian frontier post.

He records road conditions as he finds them. The Low Countries have both good and bad roads, but North Africa’s roads are excellent while those in the Pacific Northwest barely exist. “In all the world I believe the 12 mile passage of Cow Creek Canyon constitutes the limit of road badness (Frazier p.241)” he writes of Allen’s and his difficult riding there.

Clancy and Allen just miss the annual Rose Festival in Portland, Oregon, but Clancy and Storey catch Guy Fawkes’s Day in Liverpool, a city which Clancy much prefers over London. Alone or with one of his travelling companions, Clancy hits most of the major tourist attractions en route, more impressed with such European highlights as the cathedrals at Rheims or Chartres than with any monument he visits in Asia.

Much of this is filtered through what Hill calls Clancyfication: Clancy’s tendency to write broad sweeping generalization without fear and without research (not that Hill, or any other working journalist, is immune to the practice). Dublin, Clancy claims, is 50 years behind the times, which sounds absolutely up to date compared to Spain which he finds a full century behind the times. “Paris is living in its past; like London, it has had its day; unlike New York, its star is in the descendant (Frazier p.60)”, he writes in a burst of American boosterism, adding that Paris is “a place for the world’s rich to come and spend money (Frazier p.61)”. A century later, much the same could be said about New York as well.

The paseo at the Ramblas in Barcelona reminds him of the boardwalk in Atlantic City. He complains that Chicago has no “Great White Way” as does New York. Even Butte, Montana, fails to live up to his New York standards. Glasgow reminds him of any bustling American city – though apparently not specifically of New York – “but the people were – oh! so Scotchy! (Frazier p.28)”. There’s an insight: the people in Scotland seem oh so Scottish.

Just as laughable to readers a hundred years later but in a different way, is his opinion of the Japanese: “In fact, all Japan is, architecturally, a bunch of temples and some shanties, and politically nothing but a big bluff (Frazier p.217)”. Japan had already won the Russo-Japanese War (1905); annexed Korea (1910); and was more than just eyeing parts of China.

He also observes that the excitement over the California Alien Law was high, but misses what it was about, noting only that foreigners were not allowed to own land in Japan. The California Law prohibited Asian immigrants from owning land in a country of which they hoped to be citizens; the Japanese law prohibited foreigners from buying land in a country of which they had no plans to become citizens.

However, other observations are darker, some almost prescient. He notes the Home Rule debate in Parliament (1912) with the editorial aside that if Home Rule passes there could be violence in Ulster. He points out the tensions in Ceylon between the Tamils and the Sinhalese. He observes Italian troops being sent to Tripoli. The “recent revolution” in China (1911) casts a shadow over his short visit there. The effects of the two Balkan Wars (1912 and 1913) obstruct his plans to cross Iran and Turkey, requiring him to take a ship to Ceylon. From Clancy’s point of view, he wasn’t packing that pistol for nothing.

Present day readers might find some of the terms Clancy uses to describe other nationalities and ethnicities questionable, if not objectionable. In explaining what happened (or rather what didn’t happen) when Storey interviewed the Chinese counsel in New York to find out about traveling by motorcycle, Clancy writes, “With characteristic oriental skill the wily son of Confucius did most of the interviewing, and if he knew anything of the land of the Golden Dragon he was not willing to disclose it (Frazier p.11)”.

Elsewhere Clancy talks about a “black human horse” pulling a rickshaw in Ceylon (Frazier p.158) and a subhead reads ‘Gone is the “Chink” of Yesteryear (Frazier 204)’. Nor are Chinese alone in such references. A young British man is referred to as an “Englander” (Frazier p.177), which is a derogatory term, at least it was thought so when I was growing up in the United States, more than half a century later.

Because of all that period charm, it is easy to overlook that for his day, Clancy would be considered quite the liberal. Noting a bit of odd behavior on the part of one British man toward a well-dressed, well-educated Sinhalese, Clancy writes, “Their [the British] idea is that education spoils a native – that he must be “kept in his place” or else he will become insufferable (Frazier p.175-176)”. He Clancifies that as being typical of every British man, woman, and child he’s met on his globe-girdling jaunt, yet the attitude was also prevalent in the United States of his day, and lingers on in both countries to this day.

The set pieces include his adventures riding in Tunis and Algeria – he rightly milks a bit of business involving bribery, extortion, and an “Arab chief” for all its farcical worth – and the grueling ride north from San Francisco to Portland and then across to Chicago with the doughty Allen. Expanded, Clancy’s tour of Ceylon could have been a book in itself. (Sri Lanka is an oddly unexplored country for motorcycle travel: Mark Stephen Meadows’s Tea Time with Terrorists (2010) is the only other example I can think of off the top of my head.)

Clancy’s brash young American persona ages surprisingly well, perhaps because he’s engaged as much with the places he sees and the people he meets as well as what would become the more traditional motorcycle travel concerns: the riding and the breakdowns (though he has quite a few of those as well). But also as Hill observes with typical journalistic bombast disguised as an epigram: “To contemplate it was the act of a madman, and to complete it the act of a hero (Hill p.225)”. For that alone, Clancy is someone the reader really wants to like.

The first of Clancy’s two dozen dispatches describing his adventures was published on 26 November 1912 and the last on 3 February 1914. Archduke Franz Ferdinand would be assassinated five months later, and in August, the First World War would begin. The last issue of The Review was 2 February 1915, after which it was folded into Motorcycle Illustrated, where Clancy’s epilogue appears. The planned follow-up book never appeared and the story of Clancy’s globe-girdling adventures was lost to war and time.

Clancy himself went on to become a film writer, director, and producer in Hollywood, but between the change to talkies on the one hand, and the depression on the other, wound up back in the east for a long career working for the Water Board in Virginia. Although motorcycles and motorcycling seem to have disappeared from his life – so much for being an “enthusiastic” rider – there is perhaps an echo of that past in Six-Cylinder Love (1923), a Broadway play he adapted for the silent screen about an expensive motorcar that was nothing but trouble for the family that purchased it. And he ultimately did write a couple of books: The Viking Ship (1927) and The Saga of Leif Ericsson, Discoverer of America (1956), which sounds suspiciously like an old book I borrowed from the school library when small.

After Clancy died, his housekeeper gave his globe-girdling memorabilia to O’Connor, a neighbor’s teenage son. The memorabilia includes Clancy’s boots, a pith helmet he picked up in Ceylon, a couple of notebooks, and his French and British driving licenses. As it turned out the pair of notebooks are more important than the pair of boots.

Clancy may have died in genteel obscurity, but his adventures lived on, at first quietly and then with a roar. His boots were not made just for walking.

It was Schultz, who, by doing almost nothing, did almost everything. In 1994 he published Henderson, those Elegant Machines, the Complete History of Henderson Motorcycles (1911-1931) for aficionados of the once famous American marque. It is a classic example of what I call the review-proof motorcycle book. Those who worship everything Henderson will buy the book no matter how bad it is and those whose interest in Henderson is primarily academic won’t buy the book no matter how good it is.

More important the book included a brief reference to Clancy’s adventures. In Frazier’s words: “I found a small three-sentence paragraph about Carl Stearns Clancy and his accomplishment of riding a 1912 Henderson around the world in 1912 and 1913. Schultz had also included in his book a full-page copy from a 1913 sales brochure from the Henderson Company of Clancy sitting on his motorcycle after completing his ride around the globe. I was hooked like a starving fish, wanting to learn more about this monumental feat (ix)”.

Frazier, needless to say, is a Henderson enthusiast. When Schultz was unable to provide much more information than what he had included in his book, Frazier began what would turn out to be a 16-year search for the full story. Frazier is one of the better known, more respected names in motorcycle writing. In addition to being a Crow Indian (“Sun Chaser”), Frazier has a PhD in economics. His full bibliography includes more than just books about motorcycling. In short, he knows how to do real research and how to report the results.

Frazier tracked down the issues of The Motorcycle Review with Clancy’s adventures in them in libraries and flea markets. He checked what facts he could to determine that Clancy did indeed girdle the globe. Frazier even dug out what he could about Clancy’s life as well as that of Storey. Who Allen was seems to have escaped Frazier’s research at this point, which is disappointing, since Allen – the mysterious stranger who turns up out of nowhere – is sort of my pet in Clancy’s adventures.

In preparing the collected adventures for publication, Frazier made two decisions, both of which can be defended academically. The first was to present Clancy’s narrative without footnotes or corrections. The second was to reprint the photographs “as is”, without enhancing the images to make them clearer. Not tampering with the material is obligatory in academia, but despite Motorcycle Adventurer being dissertation worthy, it is a popular book. The “uncorrected” copy adds to the charm and the then contemporary references that would now need a bit of explanation can easily be cleared up with quick Google. (Hill explains the major ones in In Clancy’s Boots.) However, the muddy photographs are annoying. It would have been better to see what Clancy saw.

Frazier was unable to find a publisher, which I find appalling. He has some fourteen books to his credit, and not all of them about motorcycling. What he may have thought of the matter is anyone’s guess, but it may have involved the liberal application of four-letter Anglo-Saxon.

After making the rounds of rejections a few times, he went on to publish it himself with an introduction by Dave Barr. Barr, an inductee into the American Motorcycle Association’s Motorcycle Hall of Fame as well as a Guinness World Record holder, takes honors not only because he remembered to actually talk about the book rather than himself, but also because the introduction is a good overview of the problems of long distance motorcycle travel in the Belle Epoque. He’s a little weak on Edwardian society as a whole, but that’s not exactly his area of expertise. (Self-disclosure: as an undergraduate, I seriously considered making what is now called Edwardian literature my life’s work.)

Motorcycle Adventurer made quite a splash. The corner of the motorcycling community that is interested in travel couldn’t get enough of it and the book’s fame even spilled into the mainstream. Word of it and Clancy reached O’Connor, who by then was a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of Western Australia. O’Connor had kept Clancy’s box of globe-girdling memorabilia all those years, meaning to do something with it.

Meanwhile, Hill was beginning his plans to recreate Clancy’s trip. Hill, Frazier, and O’Connor arranged for Hill to carry Clancy’s boots on the recreation of the trip with Walker before lending them to the National Motorcycle Museum of America in Iowa, where a 1912 Henderson like the one that carried Clancy around the world is on display. I suspect that for the scholarly Frazier the real find was the notebooks. They contained a rough first draft of the book about the trip that Clancy never finished writing.

Hill is unusual in that he is a professional writer who happens to write about motorcycles and motorcycle adventure travel rather the more common case of a motorcycle adventure traveler who decides to write about one trip or another, relying more on the gimmick and a built-in audience than on actual literary talent or training.

As a journalist, moto and otherwise, Hill has published articles in a dozen or so newspapers and magazines. He has produced nine books, only five of which are travel books, one not exclusively about his motorcycle adventures. He is also an editor at Fodor’s, the international travel guide company, as well as at Ultralight Flying, a monthly periodical.

A former Irish, European, and world travel writer of the year, Hill has won or been shortlisted as the UK Travel Writer of the year nine times. He is even a member of Mensa, an organization some have described as intellectual without being intelligent. (Self-disclosure: I turned down membership; it’s not a good group for introverts.)

If anyone who writes a second motorcycle adventure travel book is a repeat offender, then Hill with four such books under his lid must be a career criminal. He also never met a gimmick he didn’t like, from riding Route 66 on a Harley-Davidson to carting India’s first tealeaves of the season to Northern Ireland on a Royal Enfield. In this case, Hill was not only following in Clancy’s intrepid footsteps in a pair of dilapidated Altberg Clubman Classic boots, but also carrying Clancy’s actual footwear in the panniers. Boots become a dark, almost perverse, literary leitmotif, starting with the title.

It took Hill three months to accomplish what took Clancy close to a year. Hill and Walker planned to use BMWs in Europe, Africa, and the US, but rent or borrow motorbikes in the Far East. The send-off in Dublin included the only Henderson in Ireland. The party continues at London’s “Ace Café” (incorrectly spelt with the aigu) and the media circus gets into full gear with a press conference and non-stop speaking engagements in Hong Kong.

Hill had to ditch the North African leg of the trip for much the same reasons Clancy had to forgo Persia and Turkey. (Plus ça change, plus ça même chose.) Even Clancy’s boots got into the swing of the whirlwind, providing Walker with emergency footgear in Hong Kong. Frazier joined Hill and Walker in California, echoing Allen’s leg of Clancy’s trip.

The boots are finally delivered to the Motorcycle Museum, which “would be the last resting place of Clancy’s boots, pith helmet, original diaries and photographs, and Irish and French driving licenses” (Hill p.224). That resting place would be near a 1912 Henderson Hill describes as “the real deal, with 7 hp, one gear, a hand-crank starter and no brakes (Hill p.225)”. Hill completes the recreation of Clancy’s globe-girdling in New York where he is welcomed by Clancy’s niece.

Hill is a humorist. As with riding and flying – he does both – those who are willing to take the risks, go to the edge, reap the rewards; in this case, the laughs and smiles. Hill uses a mix of mockery and self-mockery, wordplay and playful phrasing. If he had an Indian name like Frazier does, it would be Pun Chaser.

As Hill did in previous outings, each place is introduced with a brief knockabout history of the sort which one esteemed book reviewer in my country claims was started in Britain by 1066 and all that. I would have thought the origins were before that, in panto and music hall, if not even earlier. Some of this works; some of it doesn’t. Hill scores a funny line about Thatcher as well as a sharp observation about the Japanese surrender at the end of the Second World War.

Other jokes are feeble, if pleasant. He titles the mythic history of an island as the real history and the real history as the mythic one. The joke about not being able to get a decent cup of tea in the USA is tired and untrue. It is possible to get a decent cup of tea here, but the price will be indecent. An ironic joke about Irish history and politics is amusing in the knockabout history, but loses its edge when repeated a few pages later in the narrative.

A better example of his humor in the actual narrative is: “The last time I was there, I was shown around by a guide called Antonio who, with his shaved head, luminescent green eyes and slightly pointed ears, looked like the result of a night of unexpectedly illogical passion between Sinead O’Connor and Mr Spock (Hill p.109)”. In Clancy’s Boots is perfect for readers who like that tone and point of view.

In between summaries of what Clancy saw and did a century ago and what Hill saw and did in the recreation of the trip, Hill provides information about what changed and what hasn’t changed as well as explains what was for Clancy’s readers common knowledge, but long forgotten a hundred years later – for example that there had been a revolution in China and a war in the Balkans.

Hill notes the Chat Noir, in Paris, was not only the first cabaret as we think of such things today, but also at least 60 years before Studio 54 made the practice famous, the first place with a doorman who decided who would be let in. Hill adds that the Prince of Wales that Clancy notices at Oxford became Edward VIII. Clancy describes the young Edward as “a rosy undeveloped boy”, a phrase which could just as easily be applied to the Duke of Windsor at any point of his life.

And some things don’t change. Hill points out that traffic in London is the same as it was in Clancy’s day: averaging eight miles an hour. (I’m frankly jealous: that’s half a mile more per hour than New York, where I live.) Hill is not able to track down every place Clancy stopped or bring readers up to date on everything that passed, but the attempts contribute to the fun of the adventure.

While Hill has never been all blithe chuckles, In Clancy’s Boots has a new tone, darker, almost “chimes at midnight”. It’s in the recurring boots theme; it’s in the “comic” references to Biggles; it’s in the some of the incidental autobiographical disclosures.

The darker tone starts with the title. The leitmotif begins with the wordplay. Hill is following Clancy’s footsteps, where his boots went, while carrying the actual boots. The quote from Clancy’s dispatches Hill uses for the opening of the prologue refers to boots as well: “One must die sometime, and to die with one’s boots on is very noble (ix)”.

Clancy wrote that before the First World War when that sort of devil-may-care gung-ho attitude was common and proper. How noble any of the more than 10 million military casualties thought dying with their boots on was is open to question. Hill is well aware of that. He writes: “It took us only three hours to make the journey, travelling through Flanders, Ypres and the Somme – names which, when Clancy passed through, were synonymous with chocolate, roses and weekends in the country for the good citizens of Paris or Brussels, but in two short years became bywords for blood, mud and carnage (Hill p.64)”.

Later he compares Dresden, Pompeii, Auschwitz, and Nagasaki (Hill p.176 & 177) in terms of body counts and the lunacies of war. All are certainly horrifying events, though not exactly of the same weight. Pompeii was a natural disaster; a volcano erupted. It could be argued that Dresden and Nagasaki were legitimate war targets – the same rationale for bombing London. The death camps of the Holocaust were just slaughter based on racial and religious intolerance.

Hill shies away from that elsewhere as well in his knockabout history of France when he claims the Huguenots were exiled by Louis XIV (Hill p.63). The Huguenots were prohibited from leaving France by law. They had to smuggle themselves out. They were fugitives. Many who were caught were sentenced to the “living death” of the slave galleys for attempting to leave. (Self-disclosure: I’m an ex-oarsman; a surprising number of us rowers, current and former, are a little too interested in galleys, even when, as it does in my case, involve Vikings.)

To be fair, Hill may have been inspired by Clancy’s reference to the St Bartholomew’s Eve’s Massacre (Frazier p.72) at which tens of thousands of Protestants were killed. The ultimate number of Huguenots killed in France for being Protestant may total more than one million. Regardless, Hill shrugs off his contemplation of mass death (whatever the reason) with a mumble about “all we can do good within our own sphere of influence with every small act of the passing day (Hill p.177)” and not worry about such things as war and the like that are out of one’s control.

Yet within Hill’s own sphere of influence, there are more boots and darkness. Hill was literally on the scene when Kevin Ash was killed during a test ride of a BMW R1200GS in South Africa in 2013, shortly before Hill began his globe-girdle. They were friends and Hill’s memories of the accident scene are nightmarish, probably not helped by a number of questions about the crash that seem to remain unanswered today. Both Ash and the fatal motorcycle accident are referred to a few times in the book, which is dedicated in part to him. It may be callous to point out Ash literally and figuratively died with his boots on.

Against that, Hill’s Monty Python jokes about Biggles fall flat. To be fair, Biggles is mostly known in the US through Monty Python. The books, comics, and TV shows never quite made it across the Atlantic. The attitudes in the original juvenile series are typical Edwardian, regarding the primacy of the Empire and being game to die with “one’s boots on” in its defense.

As if that were not enough, Hill’s own dispatches about the recreation of Clancy’s trip run into some publishing issues at one paper he writes for and he loses his column in another. Little wonder that he rides off not like Biggles at the end of each adventure into the sunset, but “into the unknown future (Hill p.235)”.

Meanwhile, Frazier resolves a few questions about what Clancy may have intended as his follow up book, Gasoline Tramp. Frazier realized that there were enough differences between the original series of dispatches that were published in Motorcycle Adventurer and Clancy’s version that the draft would be worth publishing for the historic record.

The narrative reads as if Clancy were thinking of an audience closer to Biggles’s than that of Hill or Frazier. Another clue may be books or articles about long-distance walking, the only method of circumnavigation other than motorcycles Clancy cites more than once (Frazier p.7, p.287: the first official globe-girdling by foot wouldn’t be for another 60 years; Edward Payson Weston, whom Clancy mentions in passing, walked chunks of the world piecemeal and who incidentally opposed motorized vehicles). Regardless, it might be interesting to publish both the dispatches and the draft in one volume at some future date.

I recommend both books. Obviously. Reading them as a diptych would enhance both. People more interested in the history of the early days of motorcycles might prefer Motorcycle Adventurer, while those who just want a nice summer read might prefer In Clancy’s Boots.

Jonathan Boorstein

Well that’s a couple more books on my Christmas list.. Makes you wonder though just how many times the world had been circled before Ted Simon amazing feat.

You don’t want to send Father Christmas your definitive list yet Nick because Jonathan will be reviewing a whole stocking-full of books in issue 187, which will be out in plenty of time to get your orders in.