Mr Sheene

Sometime around the middle of May I spotted an Internet link to an article about one of my all time heroes so naturally I clicked on it. The photo tribute in the (London) Evening Standard said, “Yesterday marked 10 years since the death of motorcycling legend Barry Sheene” and it went on to reproduce a dozen images that provided a pretty good snapshot of his years in the spotlight. I naturally assumed that the news had slipped under my radar the day before (which, I have to admit, hardly requires stealth bomber technology these days) so I immediately Tweeted the link and posted it on both mine and The Rider’s Digest’s Facebook pages.

I couldn’t help thinking that if we were just a little bit better at forward planning, issue 178 could have reprised the obituary I wrote for the magazine a few days after Bazza died in the spring of 2003. However, having missed that opportunity to behave like a proper commercial magazine, I thought it might still be good to re-run it – albeit somewhat belatedly – to flag the 10th anniversary of the passing of one of the true superstars of motorcycle racing.

Of course when I dug out the original article, I immediately discovered that I was actually over two months too late! But I was already pretty much sold on the idea of using it by then and by the time I’d come to the end of my heartfelt eulogy, I decided it was well worth running again – even if only to introduce my hero to an even younger audience (as you’ll see the article was originally addressed to the children of the eighties, but I’m aware that there are plenty of nineties kids riding bikes and reading The Rider’s Digest these days – we’ve even got one who’s a regular contributor!).

On March 10th 2003 at 1:50pm I was sitting in my friend Steve’s flat chatting. I’d been there for about half an hour and I was just gathering my bits and pieces together to set off for an overnight at work, when Steve said: “Terrible shame about Barry Sheene.”

I hadn’t been near any news media that entire morning, so I’d been completely unaware that less than ten hours earlier, way across on the other side of the globe, the greatest personality ever to grace the stage of motorcycle racing had died. I was stunned. It wasn’t the physical kick in the gut I’d experienced when I’d first heard announcements of the sudden tragic deaths of say John Lennon or Kirsty MacColl, it was more like the tidal wave of sadness that washed through me when I heard that Ian Dury had finally checked out.

I’d read about the awful pernicious cancers that were gnawing away at Barry’s stomach and intestines but much in the same way as I had with Mr Dury, I’d forlornly hoped that the good wishes, goodwill and prayers of millions of people, would send out some sort of positive vibe that would bring about a miracle. So much for miracles.

I’d read about the awful pernicious cancers that were gnawing away at Barry’s stomach and intestines but much in the same way as I had with Mr Dury, I’d forlornly hoped that the good wishes, goodwill and prayers of millions of people, would send out some sort of positive vibe that would bring about a miracle. So much for miracles.

But it’s not difficult to understand why when the medical options started getting narrower, Sheene chose to put his faith in his God (he was adamant that he wouldn’t have chemo, saying that he couldn’t comprehend why anyone would willingly put poison into their body – which struck me as pretty ironic coming from a lifetime smoker). As a racer he’d certainly had more than his fair share of opportunities to meet his maker so who could blame him if he looked back over his miraculous death-defying escapes – and subsequent recoveries – and came to the conclusion that some greater power was looking out for him.

While I admired Barry’s faith, I’ve always been a bit bothered by his God’s propensity for moving in mysterious ways. I can understand the Christian’s rationale for why their God allowed his only son to be nailed to a cross but I honestly can’t begin to comprehend why the same deity would feel the need to treat a tenacious character like Sheene so cruelly. Why put him through the unimaginable agony of surviving a brace of 160mph plus crashes, only to carelessly take him out a few years later when he was nursing his injuries in a warm climate and enjoying the fruits of all that talent and determination? What possible Divine reason could there be for snuffing out all that life at such a ridiculously young age? And if it just had to be, why did it have to be in such an apparently spiteful and thoroughly unmerited manner? Could it perhaps be that he was being punished for contravening the unwritten rule and having too much fun?

While I admired Barry’s faith, I’ve always been a bit bothered by his God’s propensity for moving in mysterious ways. I can understand the Christian’s rationale for why their God allowed his only son to be nailed to a cross but I honestly can’t begin to comprehend why the same deity would feel the need to treat a tenacious character like Sheene so cruelly. Why put him through the unimaginable agony of surviving a brace of 160mph plus crashes, only to carelessly take him out a few years later when he was nursing his injuries in a warm climate and enjoying the fruits of all that talent and determination? What possible Divine reason could there be for snuffing out all that life at such a ridiculously young age? And if it just had to be, why did it have to be in such an apparently spiteful and thoroughly unmerited manner? Could it perhaps be that he was being punished for contravening the unwritten rule and having too much fun?

There’s little I can say to anyone who was around to witness Barry Sheene at his zenith as most of you will have a trunk load of memories of your own; but I would like to try to explain to the younger audience why he was so special. The trouble is I know that when I was in my late teens and early twenties and people of my parent’s generation began banging on about the great sporting heroes of their youth, I’d invariably nod along politely, but I could never really take them seriously. Were they really trying to suggest that Stanley Matthews – that old geezer in the jerky b&w films with the army haircut, shorts half way down his shins and miners boots – bore any comparison to Georgie Best? Or that Sterling Moss and Fangio (who I’d only ever seen on old film, sliding around in cigar shaped cars with ridiculously narrow wheels that look like home made kiddies go karts) could hold a candle to James Hunt and Niki Lauder?

So I’m aware that for a child of the Eighties it’s no easy thing to convey just what was so special about a man who was already older than your parents when he died. Sheene’s two GP titles and the peak of his fame and popularity (which has never been paralleled in British motorcycling) had come and gone before you even started school; so beyond any fleeting moment of sadness you might feel at the passing of a man who was clearly a bit of a rider in his day, why should you care now that he’s gone? Certainly not on my say so, because I’m precisely that old fart I used to nod along to.

So I’m aware that for a child of the Eighties it’s no easy thing to convey just what was so special about a man who was already older than your parents when he died. Sheene’s two GP titles and the peak of his fame and popularity (which has never been paralleled in British motorcycling) had come and gone before you even started school; so beyond any fleeting moment of sadness you might feel at the passing of a man who was clearly a bit of a rider in his day, why should you care now that he’s gone? Certainly not on my say so, because I’m precisely that old fart I used to nod along to.

So why should you be interested in the impact he had on my life? After all it was 1975 when he suddenly entered my consciousness and that’s a lot like someone trying to talk to me about the Blitz when I was eighteen. I know that many of you see pictures of your parents when they were your age, with their weird hair, cheesecloth shirts and outrageous flares, and cringe with embarrassment – but that’s just a generation thing. Unfortunately when you think your parents looked like Muppets, it can make it almost impossible to imagine that their life could ever have resembled yours in any way; that they could ever have done the mindlessly stupid things that you’ve done on a motorbike (or had sex on the sofa while their parents were asleep in another room) but chances are, if they had anywhere near as much fun as I did when I was your age, that’s precisely what they were doing.

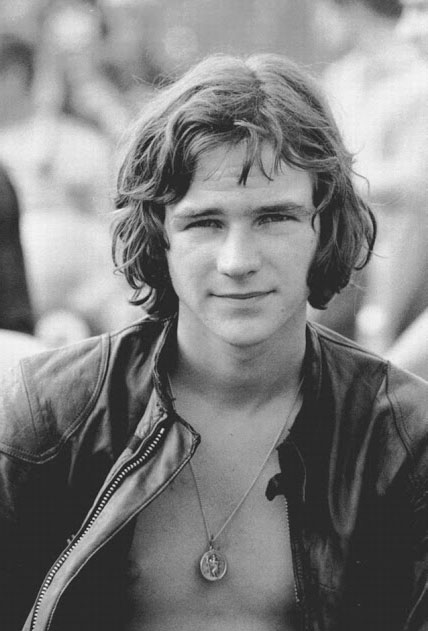

The Seventies was a brilliant place to enjoy what were some of the most wonderful and uncomplicated years of my life. At the time I’d never really thought about owning a bike. They’d always held a kind of romantic fascination, but in my mind I’d always associated real motorbikes with tatty oil-stained jeans and black leather and I was living in a bright colour-splashed world full of such delights as red hair, purple hot pants and two-tone mini skirts. So until the middle of the decade I’d paid very little attention to bikes beyond admiring particularly pretty examples when I saw them on the street. Then Barry Sheene literally crashed into my life.

In March 1975 I could have written everything I knew about bike racing on the back of a stamp. I’d heard a few of the bigger names and seen pictures here and there, I’d even seen the odd bit of footage on the box, which was probably of the TT. The trouble was whenever they wheeled a victorious rider out for a post race comment, he always seemed to be a tight-lipped northerner who preferred to do his talking on’t track. Consequently he’d stand there with that mad panda face they always had when their goggles came off and respond with nowt but “ayes” and “nays”. Then suddenly the newspapers and TV were full of the story of a brave young bike-racing prospect from London, who had had a massive off at over 170mph on the track at Daytona.

In March 1975 I could have written everything I knew about bike racing on the back of a stamp. I’d heard a few of the bigger names and seen pictures here and there, I’d even seen the odd bit of footage on the box, which was probably of the TT. The trouble was whenever they wheeled a victorious rider out for a post race comment, he always seemed to be a tight-lipped northerner who preferred to do his talking on’t track. Consequently he’d stand there with that mad panda face they always had when their goggles came off and respond with nowt but “ayes” and “nays”. Then suddenly the newspapers and TV were full of the story of a brave young bike-racing prospect from London, who had had a massive off at over 170mph on the track at Daytona.

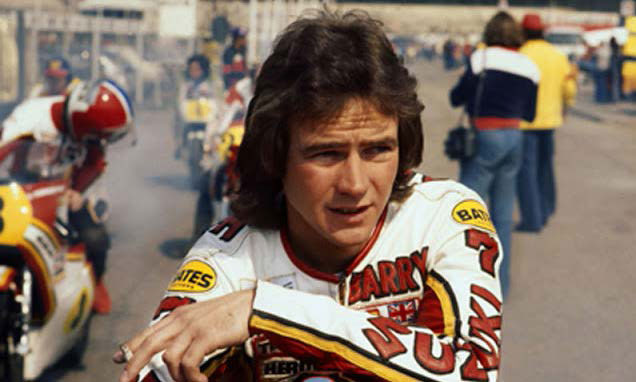

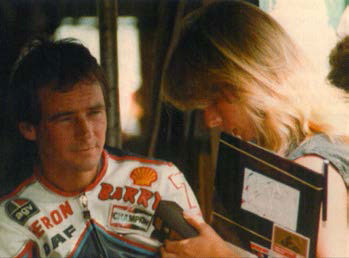

That was how and when I first became aware of Barry Sheene. Until then there had been too many other distractions in my young life for me to notice his rapid rise but someone at Thames TV had obviously spotted his potential. It wasn’t simply that he’d won the non-championship British ‘Grand Prix’ in ’74, bike racing really didn’t have any presence on the box back then, it was because he was the antithesis of the mumbling stumbling men in black who normally lifted the laurels. Sheene wore white, blue and red leathers, and had a large Donald Duck sticker above the visor on his full-face helmet; and when he removed it he revealed a good-looking young man, who was flash, enormously cocky and very quick-witted – with a tongue to match.

When Thames assigned a documentary crew to follow the young ‘Jack the Lad’ to the States, they must have been confident he was going to make good TV but they could never have imagined just how good. Literally millions of people must have stared at their screens in horror as they watched the blown-up, grainy, slow-mo film of his high-speed spill in Florida and around the same number were probably watching again the next day, as he sat up in a hospital bed smoking and joking. When asked how he was, he ran through his horrendous toll of traumatic injuries, before flashing his boyish smile and saying: “Apart from that, I’m fine.”

I was one of those dumfounded masses. I can’t speak for anyone else, I’m sure a lot of FS1E’s were snatched from protesting sixteeners and put up for sale by worried parents, but for me he was a revelation. Far from thinking: “Ouwwwch!! I’m glad I never expose myself to that sort of danger.” I looked at him in positive awe and wondered what it must be about motorbikes that would drive someone to put their vulnerable flesh and bones at such risk.

Whatever it was it had to be enormously powerful, because Sheene ignored injuries that would have dulled the winner’s edge in a lesser man and seven weeks after a smash that could have very easily finished his career, he was racing at Cadwell Park. Five weeks after that, he edged the legendry Giacomo Agostini by a few thou at Assen to take his first 500cc GP. This was just about the same time I signed a three-year Hire Purchase agreement on my first bike.

Whatever it was it had to be enormously powerful, because Sheene ignored injuries that would have dulled the winner’s edge in a lesser man and seven weeks after a smash that could have very easily finished his career, he was racing at Cadwell Park. Five weeks after that, he edged the legendry Giacomo Agostini by a few thou at Assen to take his first 500cc GP. This was just about the same time I signed a three-year Hire Purchase agreement on my first bike.

By the start of the ‘76 season, Barry’s toothy grin had been all over the media for months. A year earlier it had seemed like the entire country was behind the plucky home-grown hero – everyone loved him but by the time he turned up at Le Mans for the French GP, there seemed to be quite a few people watching simply to see if there was anything more to him than a flash self-publicising cockney playboy. By arriving with Stephanie McLean, a top glamour model and ex-Playboy bunny, he certainly lived up to that part of his reputation and as she was also married with a young son, the tabloid press had a field day (although ironically she turned out to be the love of his life).

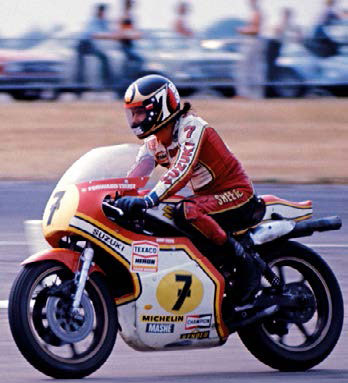

But nobody had ever accused Sheene of putting more effort into avoiding notoriety than he did into his racing and he genuinely didn’t appear to give a damn what the rags thought of him. Besides, by the time he’d annihilated the field on his new RG500, he’d shown exactly what he was made of so all the furore about his scandalous behaviour did nothing other than increase his profile and the money he received for all his sponsorship/modelling deals.

After racing on the Isle of Man in 1971 he’d sworn that it was so dangerous that he’d never ride there again. So he skipped that one; but as he had already taken maximum points from the first three races, there wasn’t really anyone breathing down his neck at that stage. In spite of missing the TT, he won the 1976 World Championship with three rounds to spare, before underlining his domination by adding the British Shellsport 500 and MCN Superbike titles to his season’s haul.

He repeated the same triple the following year and received the Sports Writers’ ‘Sportsman of the Year’ award in honour of the amazing feat. By the time the New Year’s Honours list came out Sheene was far and away the biggest name in British sport and he was earning an absolute fortune. For a 27 year old who’d left school when he was 15, the MBE must have been a real blast and the Queen gave him some very sound advice, because apparently as she handed him his gong she said: “Now young man, you be careful.”

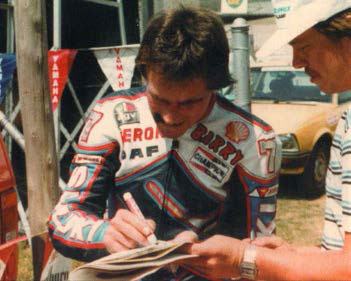

When Kenny Roberts came over for the ’78 season, Barry was riding better than ever but although most of their races seemed to go right down to the wire, the man with the eagles on his lid edged more of them and lifted the title at his first attempt. Then he did it again in ‘79. By the time the British GP at Silverstone came round, Sheene was already out of contention but with nothing aside from honour at stake, he hounded the American all the way to the line, which he crossed less than 0.03 of a second behind him.

When Kenny Roberts came over for the ’78 season, Barry was riding better than ever but although most of their races seemed to go right down to the wire, the man with the eagles on his lid edged more of them and lifted the title at his first attempt. Then he did it again in ‘79. By the time the British GP at Silverstone came round, Sheene was already out of contention but with nothing aside from honour at stake, he hounded the American all the way to the line, which he crossed less than 0.03 of a second behind him.

Barry never again reached the dizzying heights he’d enjoyed in ’76 and ‘77, but his two GP Championships in a row were still remarkable achievements – particularly when you consider that he was the last Brit to hold the GP World title. Even more importantly though, within the space of less than three years, he almost single-handedly and by sheer dint of the power and size of his personality, dragged motorcycle racing into the public consciousness. There can be no doubt that the increased sponsorship this drew to the sport, benefited everyone involved and, love it or hate it, the serious money it generated, helped to build GP racing into the amazing three ring circus it is today.

But money wasn’t the only thing Sheene’s GP rivals gained from his presence, he also made a number of principled stands on safety issues. His refusal to race in the Manx TT was undoubtedly a major factor in getting it dropped from Championship in ’77; and at the Austrian GP the same year, he led most of the leading 500cc riders on a walkout over safety facilities, after a fatal pile up in the 350 race. Barry was a great man to have on your side in any argument over track safety because his Daytona injuries and subsequent comeback were the stuff of legend so there was nobody who would dare to accuse him of being short on bottle.

In 1982 he had his other major accident; only this time it wasn’t a ‘get off’.ß At Silverstone he was tucked in doing 160mph when his bike hit a crashed motorcycle and he was thrown into the air. He’d already broken both legs and one of his wrists before he even hit the ground; and when that unimaginably painful moment finally arrived it left him with combined damage that made the injuries he picked up seven years earlier, when he bounced along the banked track in the USA, seem relatively minor. Consequently this time it took him over five months to hobble back to racing, but, whereas at the time of his smash he had been joint second in the championship (along with Roberts) by 1983 he no longer had factory support. He raced bravely until the end of ’84 season, usually praying for rain as he struggled to make the pace on uncompetitive machines, then he retired.

He built a house in Queensland, Australia and in ’87 he moved in along with Stephanie, their children and both sets of parents. Although he’d never been shy about spending it, Sheene was actually very shrewd with his money. He continued to build his fortune through his property business and his media presence in Oz was as big as it had ever been. Life definitely seemed sweet for Barry down under and in the last few years he had even been seen back on the world’s racetracks. “No worries” as the locals say. Then along came the big C…

When Barry Sheene first crashed spectacularly into my life, I was still young enough and impressionable enough for the collision to leave an indelible motorcycle shaped scar, and it’s stayed with me for the rest of my life. By the time he faded away back at the beginning of March, I was plenty old enough to know better but ultimately even the apparent senselessness of his death couldn’t begin to diminish the memory his life – nor could it extinguish the light he cast by his superhuman example and the message he delivered: that life was too precious not to live to the full.

I started out by berating Sheene’s God for failing him when all he needed was just one more minor miracle. When I wrote: “So much for miracles”, I considered putting an outsize full stop after it, because that’s how his death made me feel. But I realised that was unfair, because in many ways his life was something of a miracle in itself. So I guess that if miracles really do exist, then surely they must come from somewhere within and Barry had simply used all his up.

I started out by berating Sheene’s God for failing him when all he needed was just one more minor miracle. When I wrote: “So much for miracles”, I considered putting an outsize full stop after it, because that’s how his death made me feel. But I realised that was unfair, because in many ways his life was something of a miracle in itself. So I guess that if miracles really do exist, then surely they must come from somewhere within and Barry had simply used all his up.

Whether it was the groupie romps he’d enjoyed during his first flush of fame, his double World Championship, the staggering duels with Kenny Roberts, or setting a new 500cc classic record in 2002, there can be no question that Barry Sheene lived it large. He may have only been here for a little over half a century, but the amount of sheer living he managed to shoe-horn into that relatively short period, far exceeded anything the average person could handle in a dozen mere three score plus ten existences.

Cheers Barry, thanks for the memories.