One Moment, Please

The word ‘moment’ is having, well, a moment right now.

Katherine Rosman’s 6 June 2022 article in The New York Times included the headline: “Punctuality Is Having a Moment”. In May 2022 Vogue included a piece by Emily Chan with the headline: “Why Vintage Versace Is Having a Moment Right Now”. Even The Rider’s Digest is having a moment with its twenty-fifth anniversary.

But another definition of moment is having a moment right now, at least among overland motorcycle adventure travel writers. It’s the instance when they realize why they travel or what makes the work of travel worthwhile, a sort of aperçu or satori when they interact with the road, the scenery, or another person.

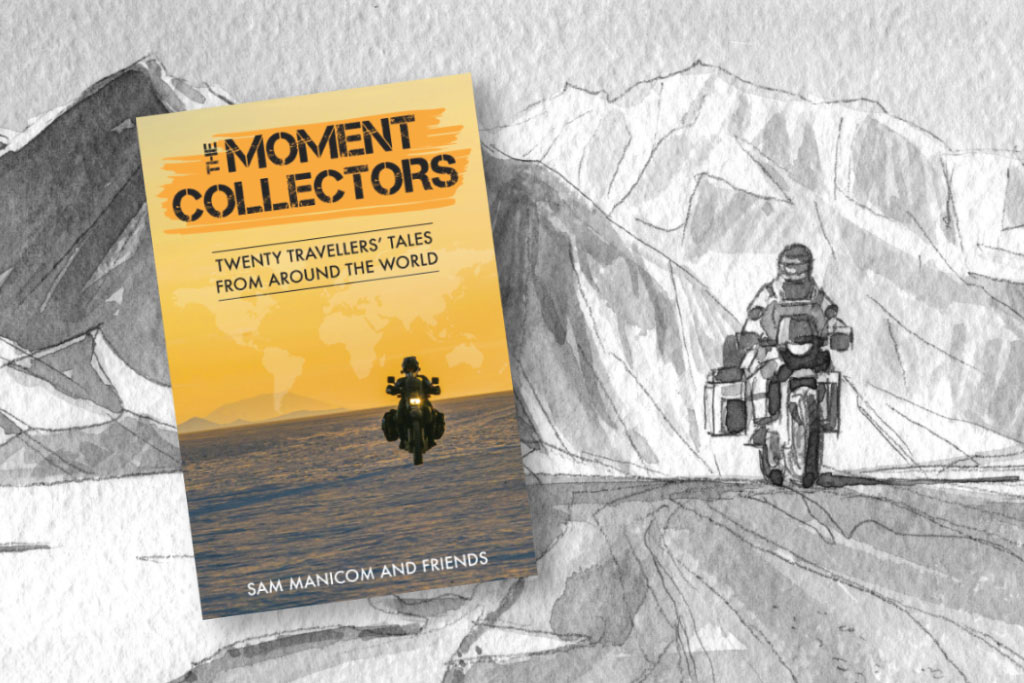

In The Moment Collectors (2022), Sam Manicom claims that such “[M]oments, be they challenges or delights, are the reasons why every long-distance international traveller is who they have become.”

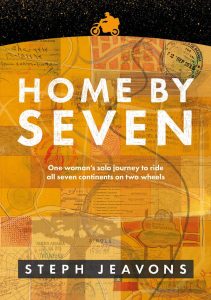

Steph Jeavons echoes that sentiment when she writes in Home by Seven (2020): “The road was full of wonderful little surprises… Chance meetings, chance moments that lift your spirits just at the right time. The more I travelled, the more I found them.”

Steph Jeavons echoes that sentiment when she writes in Home by Seven (2020): “The road was full of wonderful little surprises… Chance meetings, chance moments that lift your spirits just at the right time. The more I travelled, the more I found them.”

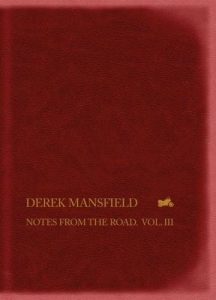

While not exactly using that word, Derek Mansfield is certainly in line with the concept of moment when he says in the prefatory pages of Notes from the Road, Vol. III (2017), “Here’s a truth that I’ve discovered. When you’ve seen sufficient oceans, and marvelled at the mountains, when you’ve walked the city street and ridden enough of the steppe… it’s the people you meet that are the most remembered. They’re the reason for the journey.”

While not exactly using that word, Derek Mansfield is certainly in line with the concept of moment when he says in the prefatory pages of Notes from the Road, Vol. III (2017), “Here’s a truth that I’ve discovered. When you’ve seen sufficient oceans, and marvelled at the mountains, when you’ve walked the city street and ridden enough of the steppe… it’s the people you meet that are the most remembered. They’re the reason for the journey.”

So, let’s take a moment to look at all three books.

Both Jeavons and Mansfield are strong writers who illustrate a point about the importance of the first ten percent of a book – any book – not just motorcycle adventure travel. As most readers know, a “good” motorcycle adventure travel memoir includes: a gimmick, the why or purpose of the trip; a number of memorable characters and harrowing rides or experiences; and a likeable or interesting narrator. It is in that first ten percent that the writer has to establish plot, tone, theme, voice, conflict, setting, character, and point of view. In the case of the sub-genre, plot is the spine or through-line of the book. It’s the road or roads taken from Utica to Ushuaia, say, or Vauxhall to Vladivostok. Conflict is anecdotal: a bureaucrat here; bad weather there; road conditions everywhere. How those elements are assembled and presented is what makes the narrative readable and the narrator interesting, if not likeable.

However, what gets the reader into that beginning is the hook. The hook can be a sentence, a paragraph, or even a full chapter, especially in older books. It’s what pulls the reader into the narrative and that all important first ten percent. Little wonder that the first ten percent is the most revised and rewritten of most manuscripts. Coincidentally, that first ten percent is 37 pages for both Jeavons and Mansfield.

Mansfield’s book covers his 2012 trip from London to Mongolia (and back) on a Moto Guzzi Stelvio. He alludes to having had nineteen previous careers before he travelled through the former Soviet Union. I’m not sure what the full list of Mansfield’s previous careers is, but to judge from his book, reporting on research and analysis played a large part in many of those careers. There’s nothing wrong with that. Basically, that’s what criticism is as well. To say it’s more than that would be somewhat pretentious.

Mansfield’s book covers his 2012 trip from London to Mongolia (and back) on a Moto Guzzi Stelvio. He alludes to having had nineteen previous careers before he travelled through the former Soviet Union. I’m not sure what the full list of Mansfield’s previous careers is, but to judge from his book, reporting on research and analysis played a large part in many of those careers. There’s nothing wrong with that. Basically, that’s what criticism is as well. To say it’s more than that would be somewhat pretentious.

Despite that, Mansfield’s book has a slow and cluttered start. It begins with some sort of preface or epigraph the title of which is a learned quote in Latin. Then there’s a dedication. Then there’s the table of contents, along with a map. Then there’s a foreword. Then there’s a prologue, complete with a “cliffhanger” of a predicament on the road. Then, finally, there’s the first chapter and the narrative begins.

The natural beginning to most travel memoirs is when the traveller leaves on the trip. Starting with some mid-trip mishap and then jumping back in time to when the trip began wastes valuable literary space and slows down the tale with artificial suspense. In a first-person narrative, it is obvious the narrator survived alive and well enough to write up the adventures. Furthermore, structurally there are only two ways to get out of any such predicament. The actual first sentence of the first chapter is so much a better hook: “It’s the drugs that take up the space.” It’s the sort of fumbling about that warns the careful reader that the writer doesn’t trust the material.

However, Mansfield quickly recovers. “I’m a couch-surfing tourist,” he explains, adding that, “I was looking forward to meeting new friends.” And couches and new friends he meets galore despite a tendency to get lost in lookalike Soviet-era cement block housing developments. He is what some call a “people person” and couch surfing lets him interact with a wider range of people with better incomes and wider experiences than the archetypal overlander.

And they have better spaces which allows them to host couch surfers. One, Mansfield notes, had “a kitchen big enough for a matched pair of epee fencers performing their stuff”. As an ex-fencer who once favored the epée (because it’s closest to an old dueling rapier) that caught my attention. Assuming he meant the length of a piste (fencing strip) that would be 14 meters long (about 46 feet) or roughly the length of one side – or two parallel sides – of the average freestanding house here in the U.S., which I presume he means is the size of that space.

The range provides more interesting reading than the more usual narrative of overlanders meeting other overlanders at bars and hostels that cater to overlanders. To be fair, for some that “echo chamber” is part of the charm of the experience. As Ted Hely says in Manicom’s Moment Collectors, “One of the best things about overlanding in this way is meeting and spending time with other travellers with vehicles.”

Mansfield weaves personal history and anecdotes into his tale of people and the road: from being a recovering alcoholic to masterminding a caper to steal back a business that had been stolen from him (and which, properly detailed, would make a great set piece in a classic men’s pulp adventure novel). But he tells more than he shows, summarizes more than he illustrates. Ordinarily this might be a liability, but here it is an asset in what becomes one of the better and more interesting parts of the narrative: his assessments of Russia and the breakaway states from the former Russian and Soviet empires. There is nothing inconsistent there from what professional experts have to say, and it’s a lot more readable. “These Russians,” he notes ruefully, “two years later applauding Mr Putin for starting the war in Ukraine and stealing Crimea. Such is the power of propaganda.”

Mansfield weaves personal history and anecdotes into his tale of people and the road: from being a recovering alcoholic to masterminding a caper to steal back a business that had been stolen from him (and which, properly detailed, would make a great set piece in a classic men’s pulp adventure novel). But he tells more than he shows, summarizes more than he illustrates. Ordinarily this might be a liability, but here it is an asset in what becomes one of the better and more interesting parts of the narrative: his assessments of Russia and the breakaway states from the former Russian and Soviet empires. There is nothing inconsistent there from what professional experts have to say, and it’s a lot more readable. “These Russians,” he notes ruefully, “two years later applauding Mr Putin for starting the war in Ukraine and stealing Crimea. Such is the power of propaganda.”

The book is a fascinating snapshot of landscapes now completely if not irrevocably changed by war, geopolitics, and Vladimir Putin’s drive to reclaim the territories Russia once occupied.

Such larger political issues aren’t Jeavons’s main concern. Although she is clearly aware of the colonialist-imperialist nature of tourism, which includes all forms of adventure travel, it’s something she shies away from. Instead, she takes a different approach which takes the reader on two journeys: an outer journey, the what the travel writer did on the trip; and an inner journey, the writer’s thoughts and feelings, changes and insights, which of course include many Manicom moments.

For example, she notes, “This moment really did brighten my mood. It had been another welcome reminder for a tired brain. This was why I travelled. There was no ultimate or constant high in life; no ‘Promised Land’, and I was OK with that. There was only a series of highs and lows and random moments like that, which, once stitched together, made a rich and beautiful tapestry weaved together by the road. The road. It brought so much – because you just can’t make this stuff up.”

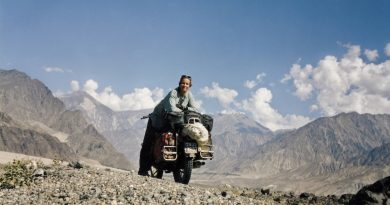

While serving time for dealing drugs, Jeavons decides to clean up and see the world when she gets out, an ambition for which a baobab tree is a goal, a symbol, and a running gag. Some twenty years later, she set out on an around the world tour from the Ace Cafe with plans to ride her motorcycle, Rhonda the Honda (a CRF250L) on all seven continents. Given the title of her book, Home by Seven, it’s not much of a spoiler to say that in April 2018, four years and 74,000 miles (120,000 kilometres) later, she roars back to the Ace having achieved her goal of being the first person to ride a motorcycle on all seven continents in one round the world trip. “We all make some bad decisions and some of them snowball to crush you,” she notes near the end of her travel memoir, “but, in my case, some of them turn into motorcycles and lead you all the way around the world.”

Instead of beginning and ending her memoir at the Ace, which would be the natural bookends for her tale, Jeavons opens with her experiences in prison, taking up four chapters and 26 pages before taking a huge jump forward in time to her send off at the Ace. There are two points of interest here. The first is that the prison chapters delay the start of the story. What elements that are necessary could have been included in passing as needed in the narrative. The second is that Jeavons is a strong and effective writer. The chapters raise the distracting question “Why aren’t her experiences before, during, and after prison a book in itself?” Parenthetically, I suspect her life between prison and her around the world trip could be a book as well. She may or may not have had as many previous careers as Mansfield, but she is not the sort of person to whom dull things happen.

Her trip, mostly solo, sometimes with others she meets upon the road, included encounters with landslides, traffic jams, sexual predators, rampaging wildlife, and even Charlie Boorman. I lost track, but she may have dropped her bike, got drunk, and sang karaoke on all seven continents as well. Among the better written and more memorable set pieces in the book are her experiences in both the Arctic and the Antarctic as well as a sojourn in British Columbia. (Has there been any other round the world motorcycle traveler who has hit both polar regions in one trip?) She has a real skill to evoke adventure in cold, hostile, but beautiful climates.

The book also traces Jeavons’s transition from tour operator and adventure rider to adventure writer and lecturer as she scrambled for money to continue her journey. Her writing itself is honest, humorous, and relatively free of self-pity and self-indulgence. (The book was edited by Digest regular Paul Nicholas Blezard as well as John Pearce.) One lecture provided a Manicom moment for Emma Lucy Cole, who claims in Moment Collectors: “Steph Jeavons’ story was not so much laid out for us as it was spread-eagled on the lecture slides and in her words, dropped with a brutal and refreshing honesty. And that was the moment I decided to become a biker.”

In addition to Cole and Nely, the other writers in Manicom’s anthology of twenty travelers’ tales include: Christian Brix, Daniel Byers, Tiffany Coates, Spencer James Conway and Cathy Nel, Mark Donham, Claire Elsdon, Graham Field, Travis and Chantil Gill, Geoff Hill, Geoff Keys, Michelle Lamphere, Helen Lloyd, Lisa Morris and Jason Spafford, Tim and Marisa Notier, Michnus and Elsebie Olivier, Brian Rix and Shirley Hardy-Rix, Birgit Schünemann (with Manicom), and Simon and Lisa Thomas. Lois Pryce contributed a nimble foreword, in which she comments, “The best moments come from the people we meet on the road”, echoing Mansfield’s sentiments.

In addition to Cole and Nely, the other writers in Manicom’s anthology of twenty travelers’ tales include: Christian Brix, Daniel Byers, Tiffany Coates, Spencer James Conway and Cathy Nel, Mark Donham, Claire Elsdon, Graham Field, Travis and Chantil Gill, Geoff Hill, Geoff Keys, Michelle Lamphere, Helen Lloyd, Lisa Morris and Jason Spafford, Tim and Marisa Notier, Michnus and Elsebie Olivier, Brian Rix and Shirley Hardy-Rix, Birgit Schünemann (with Manicom), and Simon and Lisa Thomas. Lois Pryce contributed a nimble foreword, in which she comments, “The best moments come from the people we meet on the road”, echoing Mansfield’s sentiments.

Those who follow Manicom on social media will recognize most if not all of the names, making the roster of writers look suspiciously like a round-up of the usual suspects. Given the number who have direct and indirect connections to The Digest, there’s also a whiff of old-home week.

The Moment Collectors is what some call a “Covid project”, which is to say the anthology wouldn’t have happened if it weren’t for the Covid lockdown. However, Manicom had such an anthology “in mind for around 6 or 7 years but the time hasn’t felt right for it”. He added in that email, “it really bothered me to hear how many people were saying it’ll never be possible again”.

The Moment Collectors is what some call a “Covid project”, which is to say the anthology wouldn’t have happened if it weren’t for the Covid lockdown. However, Manicom had such an anthology “in mind for around 6 or 7 years but the time hasn’t felt right for it”. He added in that email, “it really bothered me to hear how many people were saying it’ll never be possible again”.

To inspire readers to keep traveling, start traveling, or just enjoy travelers’ tales, each story was edited to the writer’s style, rather than a house style, and begins with a quote, usually selected by the author. Each tale is also identified by continent. North and South America get five each. Africa gets three; Europe, two. At least one tale could just have easily been assigned to Australia, which would have brought the continent count up to six and leaving Antarctica to Jeavons.

Each chapter has three drawings: one at the beginning; one somewhere in the middle; and a line drawing of the author at the end with the writer’s bio, all of which have charm. The bio includes contact information, from websites to social media to links to the writers’ books, if any. While editing towards the writers’s voices works wonderfully in the actual narratives, a stricter editorial hand might have applied to the author bios. Writers are notoriously bad at writing their own bios.

There is also a section of photographs poorly reproduced in black and white, at least in the hardcopy I had to review. I suspect Manicom’s ideal reader would purchase the e-book.

The back of the book is filled with pages of resources, both as an index and as space ads. “The companies who bought their space were a fantastic help with making this book happen,” Manicom said in an email. “Without these companies all jumping straight on board to be a part of the project, I probably wouldn’t have been able to afford to do it.” In other words, the revenue model is closer to that of a newspaper or motorcycle magazine: deliver an audience to an advertiser. Given the expense of (self-)publication, it may well be the wave of the future. Right now, it makes The Moment Collectors an indispensable resource for overlanders.

As for the tales themselves, the ones that focus on a specific incident or anecdote, place or person are better than those that try to cover riding across an entire continent in twenty pages. Among the tales that stand out are Cole’s A Return to Sinai, as much about memory as motorcycles; Coates’s The Kyrgyzstan Eagle Hunter, about hunters who use eagles in Central Asia; and Elsdon’s The Unthinkable Happens, about a rather odd Good Samaritan.

As for the tales themselves, the ones that focus on a specific incident or anecdote, place or person are better than those that try to cover riding across an entire continent in twenty pages. Among the tales that stand out are Cole’s A Return to Sinai, as much about memory as motorcycles; Coates’s The Kyrgyzstan Eagle Hunter, about hunters who use eagles in Central Asia; and Elsdon’s The Unthinkable Happens, about a rather odd Good Samaritan.

Of course, this wouldn’t be a Manicom production if he didn’t take a moment or two to pitch why the only way to travel to experience such moments is by motorcycle. Motorcycle adventure riders “all have an incredibly strong streak of curiosity. Motorcycle travellers revel at the buzz of freedom, which exploring on two wheels makes possible”, he notes in the preface. Pryce is more precise: “The motorcycle opens up the world in a way that a journey by bus or plane or even travelling overland by car can never do. It ignites curiosity and camaraderie in others, and inspires openness in all of us, the riders.”

I’ve had Manicom moments in museums, such as getting a private tour of a puppet museum in Atlanta despite it being closed for renovations; on trains, such as the night I spent with 26 nuns on the way to Brussels; and in antique shops, such as the time I was taken to a hidden warehouse in Seoul where the real antiques were kept. I’ve had them masked as a bauta in Venice for Carnevale and dressed in tweeds as an academic in San Francisco. And none of them directly involved a motorcycle.

I’m afraid there is no single way to have an adventure, no single way to have a moment. As Gill points out in his contribution to the anthology: “Each of us is going to have to get out there and find our own unique euphoric moments.”

Jonathan,

I have learned more about the structure of booking writing in your review than in my previous nineteen careers, only one of which, that of copywriting, had anything to do with actually writing a book.

I am so grateful for your comments and your honesty about the book itself.

Several of my manuscripts may well be on their way to you 🙂 🙂

Thank you so very much.

Best & Cordially,

Derek