Red Horse, Ready Rider

If the brutal truth be known, I wouldn’t even last ten seconds as a despatch rider. Quite odd, really, since The Rider’s Digest was started some seventeen years ago by a despatch rider for despatch riders. To be fair to myself – and if I won’t be fair to myself, who will be? – that is about five seconds longer than I would last as a café racer, another group with which this magazine is associated.

Despite my utter lack of credentials and credibility as a despatch rider, I enjoy playing off the Digest’s distant origins. Usually this is restricted to using “rider” when others might say “biker” or “motorcyclist”. But then came the ramp up to the centennial of the start of the First World War. Among its other firsts, the Great War was the first war not only to use motorcycles in general, but also motorcycle despatch riders in particular.

That was too good to resist. I lined up the reading and got to work. I wasn’t too far into the research when an odd question came to mind: Could it be argued that the centennial of the military despatch rider is also the centennial of the civilian despatch rider? Perhaps even here in the United States as well, where despatch riders are usually called motorcycle couriers? (Except in southern California, where they’re called docket rockets because of their heavy use by the legal professions.) Are the fabled Don R’s of yore the direct great-grandparents of the few and the brave civilian despatch riders who founded The Rider’s Digest in 1997?

And great-grandparents rather than great-grandfathers because women rode both military and civilian despatch to free men “for more important work” (as it was phrased at the time). What would Lois Pryce, who rode despatch for a film company while waiting to hear whether her first book would be published, have to say to Mairi Chisholm, later to be a “Madonna of Pervyse”, who became a military despatch rider in the very first days of the war?

The British military began experimenting with motorcycles in manoeuvres possibly as early as 1909, as part of the Army reforms carried out by Richard Haldane, Secretary of State for War, following the Second Boer War (1899 to 1902). Recruitment for despatch riders began in July, before war was officially declared in August. As Captain Austin Patrick Corcoran notes in Daredevil of the Army: Experiences as a “Buzzer” and Despatch Rider (1919), it was “an experiment in thus choosing us”.

The experiment extended to using motorcycles as ambulances, for escort and scouting, and carriers of small loads and brass hats (as well as other officers). Motorcycles were even used for mounted machine guns, though without notable success. Then again, nothing about Gallipoli was a notable success.

But motorcycles weren’t the only experiment. The war was also the first in which what we would now call modern communications was a factor, a factor that too often failed. When radio and telephone could not be used, despatch rode to the rescue. “[T]he motorcycle may have saved (the) Empire from military defeat”, asserts Michael Carragher in San Fairy Ann?: Motorcycles and British Victory 1914-1918 (2013).

Of course, radio and telephone didn’t always fail but field wire only went so far, was useless when the troops themselves were moving, and was vulnerable to deliberate and accidental damage. Messages that were too long or too complicated were sent by other means. Sometimes radio silence was necessary.

While such other means of communication as foot, bicycle, and carrier pigeon were used, it was the motorcycle rider that played a significant enough role in maintaining contact between and among the chain of command and various units in the field that Carragher argues the despatch riders not only prevented British defeat in the war, but also contributed to its victory.

The Motorcycle Despatch Corps belonged to the Signal Section of The Royal Engineers of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The initial call-up was for volunteers, primarily “university men”. Carl Stearns Clancy noted that students at Oxford were using motorbikes to go to and from classes during his around the world motorcycle trip (see Globe Girdlers Six). Motorbikes were as popular in other universities as well. Even though the first rounds of volunteers had to supply their own motorcycles, the London office had 2000 more volunteers than it had places. Some of the volunteers were competition motorcycle racers.

Of course, having to provide one’s own motorcycle implied having the wherewithal to purchase one. Other requirements suggesting that volunteers would have had to have come from the upper classes included some knowledge of French and German, being able to handle a gun with ease, and being around six foot or taller. Six foot six William H.L. Watson, graduate of Harrow and Oxford (Balliol, no less), simply dropped by a motorcycle showroom and bought a Sunbeam 3½ HP just so he could ride off to battle in style (Adventures of a Despatch Rider, 1915).

If the volunteer and his motorcycle were accepted, he received £10, with the promise of another £5 upon an honorable discharge. Pay was 35s per week, but was later reduced. Training was brief and rudimentary, lasting almost three full weeks. Fortunately, most public school and university men would have been in the Officer Training Corps but it is little wonder the professional soldiers in the British army saw despatch riders as amateurs or civilians.

Since messages had to be delivered in person to the officer to whom it was addressed, despatch riders were automatically made corporals. According to army rules and regulations, no man in the ranks could on his own approach an officer unless accompanied by an NCO (who may have had more important things to do).

There were three dockets: one was left at the office to show that the rider had been sent out; one was delivered; and one was a signed receipt that the delivery had been made. If a rider did not return within a specified time, a second despatch was sent out. Sometimes more than one rider was sent out with the same message at the same time.

If the motorcycle broke down, a special provision allowed the despatch rider to commandeer any vehicle, however important the occupant. One suspects the higher up in the chain of command the more cooperative the occupant would be.

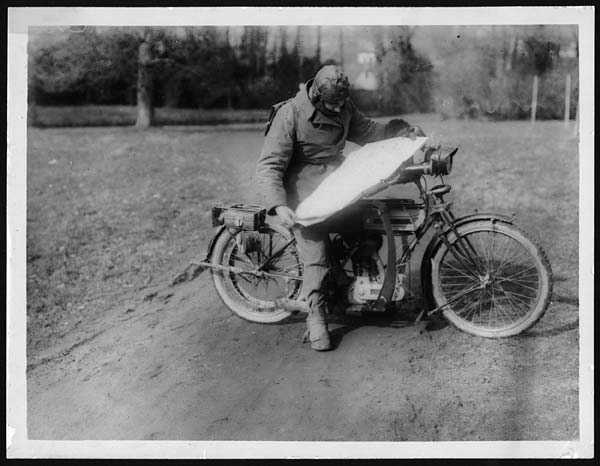

Road accidents were not uncommon, predominately falls and flats. Riders carried a kit of spare valves, spark(ing) plugs, parts for the magneto and a belt or chain, among other items. Night riding had to be done without lights adding another level of hazard, as did rain or snow.

If the rider were captured, he was expected to destroy the despatch, usually by swallowing it. Despatches were written on tissue paper, Corcoran noted, adding dryly that the military was “careful as usual of our digestion”. The riders also memorized the messages in case they managed to escape or evade capture. What captured riders may have done during interrogation is best left outside the scope of this article. Such techniques had been refined long before the Inquisition.

Being killed or captured was not necessarily uppermost in the mind of a despatch rider. “Here am I wandering out,” Watson writes, “taking orders for the complete destruction of a village and probably for the death of a couple hundred men without a thought, except that the roads are very greasy and that lunch time is near”.

Greasy roads were only part of the problem. The riders were hampered by a critical shortage of maps, and what maps there were were either unsuitable or out-of-date. The roads were the width of one vehicle, often made of mud or pavé with road metal mixed in. The slippery surfaces slimed the wheels. The military enforced a speed limit of 20 miles an hour on the riders. Not that they always obeyed that rule. Watson, “with my heart thumping against my ribs I opened the throttle, until I was jumping at 40 m.p.h. from cobble to cobble” before he realized it might be a good idea to slow down if he wanted to get back safely.

Battlefield hazards ranged from shells, attacks from enemy aircraft, and clotheslining, stringing wire about four feet above the ground which many riders felt could decapitate them. More riders may have been killed coming into camp by jumpy sentries than by enemy shells. Some were mistaken for spies. Paul Maze was lined up in front of a firing squad before a commanding officer happened to wander by and recognized him just in time.

The riders were armed. Rifles were carried in either a hunter’s sling or in a holster next to the fuel tank, which could get entangled in the motorcycle. Ultimately handguns were issued, Webleys at first, but later anything a rider could lay his hands on. The guns were so seldom used that they were often seen as unnecessary baggage.

Despatch riding in Africa or the Middle East wasn’t much better. There was sand instead of mud, of course, but charging lions and rhinos were undoubtedly a bit of a surprise.

There were five riders to a brigade, nine to a division. The initial Corps of more than 150 riders who delivered two messages an hour during the retreat from Mons grew in number. By the end of the year, despatch riders were delivering 5,000 messages daily, usually by regular route run twice a day. Only the most important messages were sent by special despatch. The riders regarded the regular run as glorified postal delivery and thought their real work were the urgent messages that had to get through regardless of all danger.

Carragher explains that by 1915 the standard motorcycle for despatch riders was “either the 2¾ HP Douglas or the 3½ HP Triumph”. Its average use in the field was about two months. And motorcycles in a battlefield were so new that the need for special clothing was not understood at first. Ultimately, some combination of leather coats with waterproofing, black artillery boots with laced leggings, and goggles and gauntlets were used.

Motorcycle production continued throughout the Great War, with some estimates reaching an eyebrow-arching 750,000 bikes. Regardless of the actual number produced, more than 40,000 units survived and the War Office sold them as surplus after the Armistice. “The plebes”, as Carragher calls them, bought the motorcycles cheap. The buyers were, more often than not, World War I veterans who came home to find no work, but needed some form of transportation they could afford.

Finding work or earning a living may have part of Corcoran’s motivations in writing The Daredevil of the Army. With mischievous humor he offers “glorified messenger boy” as an alternative to “daredevil”.

Corcoran seems to have been born around 1890 in Cork. Precise information about his father is unknown, but his mother married Edward Boyd a few years later, bringing the family to England. Corcoran claims to have “hunted in Africa, ranched in Bolivia, sailed twice around the earth”, though whether he was a ranch owner or a ranch hand, and whether he travelled first class or as a member of the crew remains an open question. Regardless it was his need for adventure that led to his enlisting as a despatch rider and after a stint as a runner, he was promoted to a “buzzer” in the Signal Corps.

He was invalided out in 1916 (the same year as the Easter Rising) and moved to New York, his papers listing a Sarah Meade as a cousin. There he met her sister, Norah, with whom he had a whirlwind romance and married in 1917. Norah Meade Corcoran was a writer, in both journalism and publicity. She was the first female reporter to be hired by Joseph Pulitzer for The New York World. At a guess, she was responsible for Corcoran trying his hand at writing, mostly fiction for pulps.

Later they both served in the publicity department of the American Relief Agency (ARA) and traveled to Moscow where the ARA was working to relieve the Russian famine of 1921. Nowadays, when we think of the Soviet Union, we think of the Stalinist era policies and practices. Josef Stalin’s predecessor, Vladimir Lenin, wasn’t quite so doctrinaire. To oversimplify a vastly more complicated situation, Lenin planned a mixed communist/capitalist system to speed Russia’s recovery from two wars, two revolutions, and such miscellaneous disasters as the famine. The ARA, led by future president Herbert Hoover, of all people, was granted $100 million from Congress (matched by private donations) and provided four million tons of relief supplies to some 23 “war-torn” countries in Europe. With the exception of Russia, the program ended in 1922. Relief to Russia ended in 1923, about a year or so after the end of the Russian Civil War.

After Moscow the Corcorans’s split their time between London and New York as working writers. Corcoran himself died of pneumonia in 1928 and was buried in Calvary Cemetery, best known among New York’s architecture buffs for its Queen Anne style gatehouse.

Their descendants are currently researching the histories of both writers and perhaps will eventually be able to answer some of the open questions about their lives.

As for Corcoran’s book, it’s brisk, bright, and breezy. Parts of it first appeared in Popular Science Monthly. The rest indicates that he had a talent for pulp and publicity. Carragher says in a magnificent example of the bland but deadly understated courtesy of the academic, “I suspect that Corcoran’s book is at least in part compiled from first-hand accounts rather than based on personal experience; nevertheless it’s an informative read, and an enjoyable one, enlivened by reluctance to let unembellished truth stand in the way of a good story” (p.259).

The best sections of Daredevil are the paragraphs recycled from Corcoran’s Popular Science articles. The sections can be easily spotted: they are specific and have a complete shift in tone. He details all but step-by-step how a despatch was sent or received; how telephone cable was laid (at a rate of six miles an hour); or how wireless (Marconi) was used in the trenches.

Here he puts each system into context. In the case of despatch riders, he explains that they were the “nerves of the modern army” whose duty it was “to carry important confidential messages of urgent importance from one staff office to another”. When a general says that he heard something or information reached him, Corcoran writes that the information was usually delivered by despatch riders, who were now motorcyclists and no longer horsemen. He goes on with some allowable exaggeration: “Battle plans were depending on the skill and luck of the heroic despatch rider”.

Gripes about military life are amusing, if predictable. Observations about the horrors of war read as if he knew he has to hit those marks. There seems to be no passion behind the words. Most of his routine personal experiences are possible, a few are even probable. Nevertheless his writing style remains vivid and vigorous.

Where the tales get tall, even if well-told, are experiences he claims were told to him. A good example is a Tom Cruise movie style escape from rampaging Germans involving a high-speed chase, exchanges of gunfire, and spooked horses along a winding French road. Precisely how one achieves any speed on muddy and slippery roads while drawing and shooting a revolver (and thus taking at least one hand off the controls – don’t ask about recoil or taking aim) is best left to Hollywood scriptwriters and stunt coordinators. But it’s rousing stuff nonetheless.

Daredevil is the summer-beach-reading of the military memoir. The technical information will provide a solid foundation for other, more serious books. The rest is enjoyable fluff.

Although Watson’s Adventures of a Despatch Rider can be read as fluff, it shouldn’t be. It is a much more serious book, written by a self-described “would-be literary bloke” with a distinctive style to back up his aspirations.

William Henry Lowe Watson was born in 1891 in Westminster, the second son of a clergyman. In addition to his formal education at Harrow and Oxford, he visited Paris and Switzerland, places where French, and perhaps some German, are useful. Adventures of a Despatch Rider was written during the war and he followed up with A Company of Tanks. Somewhere in between his military vocation and literary avocation, he found time in 1916 to marry Ruth Wake-Walker, who came from a distinguished naval family. They had three children, the eldest of whom was named Patrick after Watson’s father. Ultimately, Watson became a major in the machine gun corps and received a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and a Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM). He died in Wimbledon in 1932.

Adventures started out as a series of letters Watson wrote to his mother, Elizabeth, and a friend, Second Lieutenant Robert B. Whyte, First Black Watch, BEF. Mother Watson seems to have been something of an amateur literary agent. She showed them to Townsend Warner, Watson’s tutor at Harrow as well as his “godfather in letters”. From there the letters found their way into Blackwood’s Magazine, casually referred to as “Maga”, and later, after Watson assembled and revised them into a connected narrative for the book, which was published in 1915.

As Watson implies in the epistolary introduction addressed to Whyte, Adventures is not the sort of book they talked about Watson writing back in university. He planned to write an Oxford novel, a sub-genre almost as small as motorcycle adventure travel. The three best-known Oxford novels are probably Zuleika Dobson, Gaudy Night, and Brideshead Revisited: a scary selection considering that none are exactly the expected tales of highborn youth and eccentric dons at play. The first is Max Beerbohm’s satire of the sub-genre, in which the fate of the Oxford crew isn’t that funny to this ex-oarsman; the second, a Lord Peter Wimsey murder-mystery by Dorothy L. Sayers in which the ethics and excitement of scholarship and living an intellectual life play an important part in the plot (significant clues about the facts and motivations of the crime are hidden in the academic debates); and the third, a nostalgic mood piece by Evelyn Waugh about an idealized past that never was, that has something of a cult following outside the sub-genre. Both Waugh and Sayers rode motorbikes, oddly enough.

That so many of the letters were written to his mother (to whom the book is dedicated) forms and informs the content. She was interested in what he was doing, whether he had enough to eat and a warm and dry place to sleep, but not in others she never met or didn’t know. There was censorship of course, probably relatively light considering his social class. “My only object is to try and show as truthfully as I can the part played in this monstrous war by a despatch rider during the months from August 1914 to February 1915”, he writes.

Mother Watson proved to be the ideal audience for his book, which covers the Great Retreat. The BEF stopped the German advance, but was wiped out. Refining that to the human level gives Adventures an intimacy and immediacy often lacking in war memoirs and military histories. Nor does writing to his mother inhibit his mentioning pretty women he notices or the darker sides of a battlefield. And his literary pretentions prove not to be unfounded: he writes with wit and style. “But the sharp morning air, the interest in training a new motor-cycle in the way it should go, the unexpected popping-up and grotesque salutes of wee gnome-like Boy Scouts, soon made me forget the war”, which he refers to as the Austro-Serbian at the beginning of the first chapter.

He evokes place with such passages as “The room was full of noises – the cackle of the telephones, the crooning of the woman, the croak of the wounded old man, the clear and incisive tones of the general and his brigade-major, the rattle of not too distant rifles, the booming of guns and occasionally the terrific, overwhelming crash of a shell bursting in the village”.

And Watson is willing to go for the occasional horrifying image: “Across the saddle-bow was a man with a bloody scrap of trouser instead of a leg, while the rider, who had been badly wounded in the arm, was swaying from side to side”.

He also notes which women are pretty, which are clean (an obsessive note in his descriptions). Some seem decent sorts; others are called “flappers”, which at that time was a young woman, late teens to early twenties, looking for fun and sometimes a man in khaki. In the Edwardian Age, flappers still had an echo of its Victorian meaning, which was prostitute. Watson is too much the gentleman to specify whether the flappers he met were amateurs or professionals. Observations about civilian approaches and attitudes aren’t restricted to women, however. Watson notes the hostility he and his fellow soldiers receive in Ireland. Less than two years later would be the Rising.

His observations wise and witty extend to his actually despatch riding. He complains at one point, “It is a diabolical joke of the Cosmic imps to put fog upon a greasy road for the confusion of a despatch rider”. And more seriously he explains that “The experienced motor-cyclist sits up and takes notice the whole time. He is able at the end of his ride to give an accurate account of all that he has seen on the way”. Watson even acknowledges the somewhat contradictory impulses the motorcyclists in the Signal Corps had: “Despatch rider have muddied thoughts. There is a longing for the excitement of danger and a very earnest desire to keep away from it”.

Because he was publishing the letters while he was writing more letters which then were revised for the book, Watson includes disclaimers about things being what he saw at the time and in one case left what he thought happened and then inserted what he was later told what happened, which he notes as a change from what had appeared earlier in Blackwood’s. This self-consciousness almost brings Adventures into the realm of what might be called the meta-memoir.

This consciousness of his being read is reflected elsewhere as well. Early in his Adventures he notes humorously, “George, our champion “scrounger,” discovered a chicken-house. It is true there were nineteen fowls in it. They died a silent and, I hope, painless death”. Fewer than a hundred pages later Watson says with equal humor, “We are all hoping [the shrapnel] will kill some chickens in the courtyard. The laws against looting are so strict”. And as if doing his duty to Britain were not enough, he tries to use his position as an accidental war correspondent to inspire others to do theirs as well: “Yet it is said there are still those at home who will not stir to help. I do not see how this can possibly be true. It could not be true”.

Although he is horrified by such things as his fellow soldiers looting dead bodies for food or souvenirs, he is aware of the coarsening of his own sensibilities. He realizes how alienated he feels from anyone who did not experience what he experienced. Watson writes of seeing his first corpse: “I am afraid I was not overwhelmed with thoughts of the fleetingness of life or the horror of death. If I remember my feelings aright, they consisted of a pinch of sympathy mixed with a trifle of disgust, and a very considerable hunger, which some apples by the roadside did something to allay”.

“We did not understand what an enormous, incredible thing modern war was – how it cared nothing for frontiers, or nations, or people”, is Watson’s grim observation. “In a modern war there is little room for picturesque gallantry or picture-book heroism. We are all either animals or machines, with little gained except our emotions dulled and brutalized and nightmare flashes that cannot be written about because they are unbelievable”.

Behind Watson’s humor and his elegant and seemingly effortless writing style are reticence, intelligence, and an inherent decency. The smooth style makes Adventures easy to read, and perhaps ignore some of the darker, more reflective elements. Little wonder, Carragher says, “There’s something seminal about this account given that it is not merely drawn from letters scribbled in the heat of action, but written by something like the very archetype of the “original” DR: a son of privilege, a graduate of public school … and Oxford, a self-confessed coward who, as a slave to duty… evolves into something that no reasonable human being would begrudge acknowledging a hero” (p.262).

The edition I read was retitled A Motorcycle Courier in the Great War: the Illustrated Edition, and edited and introduced by Bob Carruthers. The introduction was good enough. Where this edition excels is in a wonderful selection of photographs illustrating Watson’s words, with the pictures placed as close as possible to the relevant text.

It is unlikely, but not impossible, that either Corcoran or Watson continuing riding motorcycles after the Great War. That so many motorcycles were dumped on the market so cheap anyone could buy them certainly didn’t stop others of the better sort from continuing to ride. T.E. Lawrence (of Arabia) is probably the best known example. But of course he rode Brough Superiors and not military surplus.

Carragher rides, though probably neither Broughs nor surplus. More to the point, his background includes an M.A. in First World War Studies from The University of Birmingham, which in itself has connections to the world of motorcycling. Carragher, incidentally, has also been an editor at Bike Ireland as well as a secondary and vocational school teacher.

San Fairy Ann? is a scholarly work, which means it presents an argument – in this case, that the motorcycle despatch rider was instrumental in winning World War One – which, in turn, is supported by evidence (research) and secondary arguments. Furthermore, the argument is addressed to a specific audience – here, military historians in general and First World War historians and buffs in particular. Scholarly works also assume a certain body or level of knowledge on the part of that audience. In San Fairy Ann? it’s intermediate to advanced. Readers had better know their Schlieffen Plan from their Zimmermann Telegram. In addition, some scholarly works assume a particular political perspective or point of view, among other things. In Carragher’s book is it British and conservative, if not right-wing.

To oversimplify Carragher’s basic argument here: communication is a key element to any military operation and during the Great War communication was usually executed by despatch riders on motorcycles. Furthermore, the spirit or sensibility which empowered the riders to deliver despatches under often difficult circumstances is epitomized by the fractured French phrase, “San Fairy Ann”, or “ca ne fait rien”, which is usually translated into English as “it doesn’t matter”.

Emphasizing that military success is dependent not only on knowing what the enemy is doing but also being able to move quickly in reaction, Carragher says, “Before the age of electronic communications, the despatch rider, whether galloper or motorcyclist, was starkly essential to maintaining an army in the field, and never was this truer than in the Great War” (p.118) because the “technology of weaponry, combined with the unprecedented scale of war, had so overtaken technology of communication that battlefield control often was poor and frequently was lost” (p.119). The despatch rider, he adds, “was vital to retreating in good order and holding the Army together” (p.126) the “lynchpin … when both cable and wireless more often than not were “dis”?” (p.247).

That “hidden” contribution didn’t just lead to an Allied victory, but a British victory. The rest of the Allies played little or no part in defeating Germany. Carragher also maintains that the main theatre of war was the Western Front. He dismisses the Easter Rising and the Maritz Rebellion, Africa and the Conscription Crisis, Salonika and Gallipoli as “sideshows”. To be fair, he does describe the Mideast campaigns as the most wasteful of the sideshows. Few would argue that they weren’t wasteful and perhaps that the consequences of that sideshow continue to lay waste to the region to this day.

That “hidden” contribution didn’t just lead to an Allied victory, but a British victory. The rest of the Allies played little or no part in defeating Germany. Carragher also maintains that the main theatre of war was the Western Front. He dismisses the Easter Rising and the Maritz Rebellion, Africa and the Conscription Crisis, Salonika and Gallipoli as “sideshows”. To be fair, he does describe the Mideast campaigns as the most wasteful of the sideshows. Few would argue that they weren’t wasteful and perhaps that the consequences of that sideshow continue to lay waste to the region to this day.

While the British were relying on despatch riders more than on electronic communications, the Germans were totally dependent on wireless. They had made no provisions for its failure, which proved to be at least as often as it was for the British. Carragher suggests that the German defeat at the Marne came from a communications failure. “But they may have underestimated the value of the motorcycle despatch rider from the outset… and in the early phase of the Somme a captured report written by General Sixt von Arnim admitted: “The establishment of motor cycles proved insufficient for the heavy fighting; the deficiency was painfully in evidence””. Carragher also quotes a magazine editorial, which notes, “British motor cycling services are to be congratulated as… being at least one branch of the Services whose superiority the Germans have never challenged” (p.90).

Behind that superiority was a spirit that Carragher dubs “San Fairy Ann”. It was not the only bit of fractured French the British Military produced. Ypres became Wipers; Etreux, Extroos; Ouderdon, Eiderdown, Le Cateau, Lee Catoo; and Beoscheppe, Bo Peep, which is my favorite. No deep intellectual reason why: it just made me smile.

For Carragher the San Fairy Ann spirit means more than ca ne fait rien, it doesn’t matter. It means not only putting one’s duty before one’s self, but also executing that duty to the best of one’s ability. He feels Roger West epitomizes that sensibility among the earlier groups of despatch riders. West, a graduate of Cambridge, fluent in French and German, who, despite a foot that was so injured and infected he couldn’t wear a boot, rode back during the Great Retreat to blow up a bridge that was open to the German advance on the grounds it “seemed a pity” not to.

Seems more a pity that the very real contributions of the despatch riders are not that well-remembered today. Carragher suggests their very ubiquity may have led to relative obscurity. Yet, “During the war motorcycles were “regarded as an inseparable part of a modern army” … “as much a fixture as the machine gun” … “motor-cycle despatch riders, leather-jacketed and mud-bespattered, the light horsemen of modern war” (p.44). They were even popular figures in both the news and the pulps.

Another reason may be that motorcycles themselves were overshadowed by the glamour and advances of tanks, aeroplanes, and increasingly reliable electronic communications. In comparison, the motorcycle changed very little. Yet it was the motorcycle that carried the film taken by the reconnaissance plane to be developed; carried the results to where they could be analyzed; and then carried the instructions drawn from the analysis to the front lines.

Carragher also speculates the contemporary self-serving accounts may have diminished the role of the despatch rider as well as the Second World War overshadowing the first in general and the contribution of the despatch riders in particular. Post-war culture tended to focus on the soldiers in the trenches and on the front line. He even suggests there may be some Oedipal jealousy on the part of those involved in World War II of those involved with the Great War. He notes ruefully, “But in overlooking the despatch rider posterity may have lost sight of the man, who, though he never could have won the war, may well have prevented it from being lost” (p.28).

Carragher doesn’t overlook such minutia as pay and working hours and conditions. He reviews the history of marques and models used by Allied forces from BEF Triumphs to NATO Kawasakis to prove that the British motorcycle of the First World War was the best machine available, way ahead of comparable German and American motorcycles. He also crunched the numbers of how many motorcycles were manufactured in Great Britain during the war and by which manufactures, the other side of the glamour of scholarship that Sayers wrote about. But the results are readable, interesting, and necessary. Some of his numbers were used in the beginning of this article. He connects the surplus bikes to the fading memories of what the despatch riders did for Britain. “After the war, up to 40,000 surplus motorcycles were dumped on the market, and the motorcyclist became more proletarian, his importance, perhaps, easier to dismiss in a still socially stratified world” (p.248).

Incidental to the book’s premise of the contribution of the despatch rider to British victory in World War One and the San Fairy Ann spirit behind it is Carragher’s taste for trench poetry. It’s interesting, but it’s not consistent. A trench poem begins the introduction and five out of eight chapters of the book. It would have been better if a trench poem had begun every chapter. The section dealing in part with trench poetry proves his fields of expertise do not extend to either English literature or critical theory.

He asserts that trench poetry in general and the poets he likes in particular don’t get the respect or publication he feels is deserved because the contents of the poems do not fit into the “liberal” world view. Trench poetry, like biker poetry and cowboy poetry, gets “no respect” because they are all seen as low art, not high art, a division typical of the conservative point of view. (There a few notable exceptions on both sides.)

Carragher’s passion for Gilbert Frankau might be better served by not claiming his obscurity is due to his not towing the liberal line, but by editing an anthology of Frankau’s poetry, even though he was more the novelist. (Frankau is best-known here in the United States for having written the original story upon which the movie Christopher Strong is based.) That such conservative writers as Waugh or Kingsley Amis continue to enjoy popularity despite some unpopular opinions (at least among their liberal readers) would seem to suggest that Frankau’s relative obscurity may be due to reasons other than his politics and could be thoroughly deserved.

Liberals are something about which Carragher likes to go off on irrelevant rants. Americans are a close second. Liberals are blamed for everything from the relative obscurity of Frankau and importance of despatch riders, to changes in military strategy and deployment of men and material. Carragher rants on about the liberal contempt of patriotism in several places, though the only patriotism that earns liberal contempt is the sort the Tory writer Samuel Johnson had in mind in the aphorism, “Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel”. The war crime trials following the Second World War probably had more to do with undermining the sort of pure or simple “this piece of green, this England” patriotism that Carragher admires.

There is something he calls a “faux-liberal” the precise definition of which is unclear, to say the least. The term suggests that it is in contrast to real liberals, but what the difference between the two may be is never explained. I suspect he means liberals in general in which case Carragher needs to develop some more backbone and ditch the pretentious prefix.

Lloyd George and Joan Littlewood are the two liberals who particularly annoy Carragher. From a century and a continent away, I must say Lloyd George doesn’t seem to be any better or any worse than any other politician of his age, which in fact may be the problem. He did introduce a social welfare system, which is always a good move for those who want to irritate conservatives. I’m going to give Carragher a pass on Lloyd George. San Fairy Ann? does assume a better than average knowledge of the First World War; Lloyd George himself is outside the scope of the book; and the case against him may well have made elsewhere.

As for Littlewood, I had to look her up. She does not seem to have the reputation in the United States that she has in the United Kingdom. Her magnum opus – for lack of a better term – Oh, What a Lovely War! didn’t even last four months on Broadway. If it played anywhere in the US since the early sixties, I was unable to track the production down. It’s best known here for the Richard Attenborough film version, Oh! What a Lovely War. (I have no idea why the exclamation point was moved.) The uncredited auteur of the film was Len Deighton, a military historian as well as a well-known thriller writer. Littlewood hated the film, which she felt missed her point about the vulgarity of war. There have been several major revivals in Britain of her work over the past 50 years, including one earlier this year in London. The continued popularity of Oh, What a Lovely War! as well as what Carragher calls it, is its reflection of the cynicism of the Vietnam War ear which he feels contributed to a negative, and perhaps neglectful, view of the Great War.

What Carragher might think of Darling Lili, a romantic comedy musical set during the Great War in which a German spy is the love interest for an Allied army officer is all too easy to guess. What is ca ne fait rien here is that she’s a spy, but it doesn’t matter, and they go off happily ever after. Not even the determined professionalism of the two leads – Rock Hudson and Julie Andrews – could save it. We’re not talking Wings or Grand Illusion here.

As for Americans, someone needs to explain to Carragher that the movie cowboy who had “spurs that jingle jangle jingle” was Gene Autry not John Wayne as well as calling Americans Yanks is acceptable only if you’re British. For those British whose life ambition is to be condescended to by Americans, this is a great way to do it. As for Susan B. Anthony’s opinion about the relationship between bicycles and feminism, it is reasonably well-known here in the States, but she was an American. A similar weight quote from Mrs Pankhurst might not be as well remembered in the US. I’ll leave it to military historians to deal with his opinions of the American contribution to both World Wars.

Carragher’s field is neither literature nor popular culture. Within his topic, San Fairy Ann? is excellent and well worth reading. It’s a chapter of motorcycling history that really hasn’t been covered before, let alone this thoroughly. He does assume a certain level of knowledge on the part of the reader, but this should not be regarded as a negative. Unfamiliar references can be easily looked up.

In addition to those three books, there’s Maze’s Frenchman in Khaki (1934), the memoir of an Anglo-French British officer who was the liaison to the French forces. He wasn’t a despatch rider, though his duties often required he carry messages back and forth. Fascinating read, and a great introduction to the First World War, but ultimately not that much about motorcycles or despatch riding. I probably shouldn’t mention Aldo Carrer’s Motociclette in divisa nella grande guerra. Ediz. italiana, inglese e tedesca – conflict of interest since we’re friends on Facebook – but shall anyway. The book is a fantastic treasure trove of vintage and period photographs of the motorcycles of the war.

In addition to those three books, there’s Maze’s Frenchman in Khaki (1934), the memoir of an Anglo-French British officer who was the liaison to the French forces. He wasn’t a despatch rider, though his duties often required he carry messages back and forth. Fascinating read, and a great introduction to the First World War, but ultimately not that much about motorcycles or despatch riding. I probably shouldn’t mention Aldo Carrer’s Motociclette in divisa nella grande guerra. Ediz. italiana, inglese e tedesca – conflict of interest since we’re friends on Facebook – but shall anyway. The book is a fantastic treasure trove of vintage and period photographs of the motorcycles of the war.

As for my whimsical question about civilian despatch riders after demobilization in 1918, that is outside the scope of Carragher’s inquiry though he does discuss both civilian as well as military despatch riders on the home front during the war. Such riders were women or boy scouts.

The sad/funny story is that thousands of veterans came home to find no work and little sympathy, something faced by too many veterans of wars before and after the First as well. Some of those former despatch riders bought surplus motorcycles to earn a living by continuing to deliver packages and messages, but for civilians, dodging London traffic instead of bullets, and in their own way, got on with it, not without a certain amount of san fairy ann.

Jonathan Boorstein

As a sixteen year ‘veteran’, dodging London traffic in the 70s, 80s and 90s myself, this is a fascinating insight into the earliest days of motorcycle couriers.

It’s remarkable to think that it took wireless telegraphy 80 more years to all but kill off a profession that had its roots in the horrors of the Western Front, a profession which aside from the bloodrunners is pretty much reduced to scooter riders vying to deliver the fastest sushi in town.

A great read – thank you.

There is another version of the Watson account, called ‘Two Wheels to War’, which has the original text, and interesting footnotes indicating wht was redacted for publication. It also has photos from an album compiled by the Burney brothers, who were the artificers in Watson’s company, showing many of the main characters in the book, and their circumstances:

https://www.helion.co.uk/browse-title-series-more/two-wheels-to-war-a-tale-of-twelve-bright-young-men-who-volunteered-their-own-motorcycles-for-the-british-expeditionary-force-1914.html