Road Positioning

A few months ago I was banging on about observation and the vast amount of information we are able to take in and use, in order to make our progress through Croydon just that little bit safer.

As highly evolved binocular animals our vision has the potential to be pretty excellent but only if used effectively.

Being able to see 10MB a second is only useful if you put yourself in a good position. While you are sitting 10ft off the bumper of the transit with painted windows, the 10MB you can see is precisely squat. The only way you will improve your ability to read the road ahead is if you improve your ability to put your bike somewhere that enables you to see it in the first place. As the DSA snappily puts it “Position for Vision”.

Advanced riding is all about this. To learn how to get your knee down, do a track day. To learn precognition and get second sight, do an advanced riding course, or become a courier – the end results are similar.

The first thing I learnt on the IAM course is that to go any faster you have to learn how to hang back. This basic principle can be expressed concisely in the following equation, which came to me one evening in the bath, while mulling over this very issue: Progress is inversely proportional to proximity.

I leapt out of the bath and got on the phone to one of my best instructor friends to share this earth-shattering concept with him. After excitedly blathering for a few minutes, I paused to let the full impact of what I’d just told him, sink in.

“Well? What do you reckon?”

He drew a long, and I suspected an awed, breath.

“I reckon, doll, that you really need to get out a bit more.”

Goddamit; why is the world so slow to recognise genius?

I’m going to pinch one of Keith Code’s excellent ideas from ‘Twist of the Wrist’ here, and talk about available attention. Its fairly straight forward – In terms of available attention, if you are riding up the arse of the mini in front you’re using about 75% your attention just keeping your precise distance from said mini, and will therefore be stuck there for hours because you haven’t got enough left to plan your overtake.

A learner-riders attention is a fragile and over-wrought thing. At least 30% of it is taken up with various futile thoughts, like: ‘Oh my god, a roundabout! Which shoulder am I supposed to be looking over?’ and ‘Damn, the lights have just changed to red and now I’m going to have to stop and I’ve forgotten if she said turn left or right and where’s the bloody indicator gone anyway…’ That sort of thing. Another 10% is taken up with the never-ending mantra of the student Biker: “If I get it wrong, it’s really going to hurt.” So now we have an inexperienced rider on the mean streets of the UK with only 60% attention left for what is actually going on around him. For the purposes of this study we are going to assume that its not raining and that he’s not using up another 25% thinking about how cold and wet he is and if its possible to get trench-foot on a motorbike.

So what does our dear sweet novice do now? He gets himself 150cm off the bumper of the car in front thereby committing his last precious neurons to a detailed and constant up-date of that exact 150cm of empty air between himself and oblivion, or badly stained trousers at least.

I don’t drive cars, and as a result it took me a while to work out where this utterly insane behaviour comes from, but eventually the penny dropped.

A car driver on his first outing on the open road on two wheels will generally show his true colours as it were, and revert to type. This is normal human behaviour: Put a human under a new stress and said human will generally try and translate the new stress into one he is already familiar with. Faced with the new stress of being on a road on a motorbike, this often means they will sit in their lane where they would normally sit in the drivers’ seat of their car: So far right of dominant that they’re in danger of getting clipped by a passing wing-mirror, and nearly a whole 6 feet off the car in front. I’m amazed how often you have to point out to some people that ‘tail-gating’ at 60mph might seem fairly harmless in a big car with a four foot ‘battering’ ram of steel in front of you, an air-bag and a seat belt, but when those four feet are merely thin air, it should seem to any reasonable monkey that its more-or-less suicide to sit so close.

Cars sitting too close are scary, cars with lights on are very scary, and, as I remind my students, bikes with lights on are terrifying because the old dear in the fiesta in front thinks you’re a raving Hells Angel and are about to do something disgusting.

“Yes, I know you’re a pleasant civil servant from Ealing, but as far as that ‘vulnerable’ road user is concerned you are hoodlum on wheels and you’re freaking her out. Do your bit for biker PR and back off.”

A healthy separation distance means you don’t end up in the wrong lane at an unfamiliar junction because you couldn’t see the directional arrow on the road until you were on top of it. It means you don’t suddenly catch a glimpse of the road you are looking for, just as you irretrievably ride past it. It means you spot the pothole before you drop into it and instantly find the hardest piece of the motorbike meeting the very tenderest pieces of you – what we call a real ‘nut-cracker’, and another reason why it’s so great being a girl on a bike.

Once you’ve got yourself room to think and breathe, you can really start to benefit from the bike’s agility on the road. A meter or two, left or right can make a vast difference to your ability to see what might be coming up round the next bend. Having said that, the first rule of road positioning is ‘Never sacrifice your safety for your position’. The second rule is that there are no more rules.

Picking up a student, fresh from CBT, brimming with new knowledge and enthusiasm, it can be hard to disillusion him that sitting nice and tight to the white-line, when turning right minor-major is always the right thing to do.

“But my CBT instructor said….”

“Yeah, but there’s a removal van parked on the corner and you are now blocking this road to that car that wants to turn in.”

You can’t afford to stick to too many rules as a biker. There is ‘best practise’ and there is real-life, and your job as a biker is to bridge this gap using a) your hugely under-used brain and b) the enormous potential of the machine underneath you to “facilitate the free-flow of traffic in either direction”.

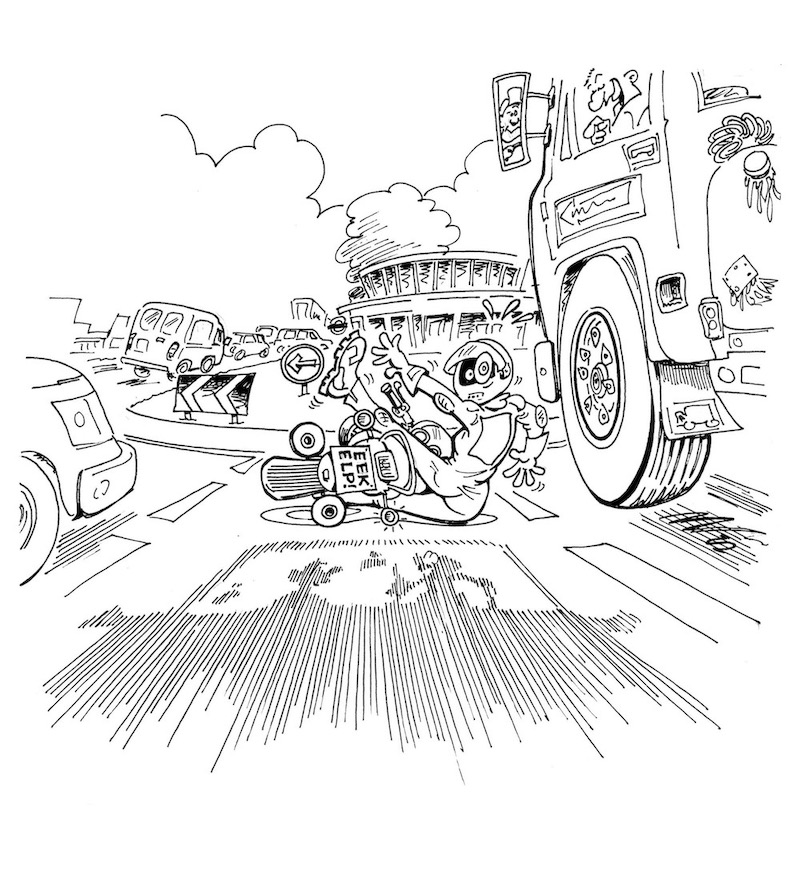

Experiment with your positioning. Lots of bikers in town ride automatically on the right, towards the crown of the road. Number one, you shouldn’t really be doing anything automatically while riding. Think about everything you do on a bike. You are too vulnerable to do anything you cannot justify. Number two, how many roads do you ride down that don’t have any side-turnings? While you are out on the crown of the road craning to see down the outside of the Sainsbury’s lorry, there’s a side-turning coming up with a Range-Rover-Mum in it and the bus behind you has stopped. In about 30 seconds you might be having one of the common bike accidents that occur when RRM T-bones you as she goes for the gap between Lorry and Bus, utterly unaware until you reshape her bonnet, that it wasn’t a gap at all.

Dropping over to the left every now and then and having a look up the inside will stop this kind of thing happening.

The space around a biker constitutes levels 1,2 and 3 of his primary defence system. This needs to be kept in good condition, because his secondary defence system – mostly dead cow and polystyrene – aint all that.

A biker can fully control the space around him because he can react to it much more subtly than a car can. Excellent throttle control, anticipation and good body language are essential in creating and maintaining your space. Being confident that you can put the bike exactly where you want is also pretty fundamental. As with all things in life, practise makes perfect, so make up games to play while you’re mucking about in traffic: Always ride on the black-stripes on Zebra crossings (then when its wet you wont even have to think about it); Change lanes on major roads without touching white-paint or a cats-eye.

Good road positioning should dramatically reduce your risk of getting more intimate with the tarmac than you want to.

Even at standstill, as you get used to reminding your hapless learners, you need a good bikes length between you and anything else; “Why? We’re not moving?” questions the muppet, until I gently point out to him that being reversed over is a horribly undignified way of getting off your bike.

Flashback to Hangar Lane at rush-hour many moons ago; the transit rolled back before moving off and left me flapping around like a stranded fish stuck under the rock of my bike, as sniggering traffic streamed around me… I still wake up in a cold sweat over that one.

The DSA manuals may tell us what to teach, but the whys and wherefores will inevitably be drawn from their instructors’ hard-won experience.

Lois Fast-Lane

This article first appeared in issue 103 of The Rider’s Digest in April 2006