The Enfield Diaries – Life begins…

When my shiny, new Enfield stalled in the chaotic Chennai traffic for the umpteenth time and I was deafened and choked by buses, lorries and motor rickshaws, I wondered if I’d made the right decision to spend £1,000 on this machine for my 50th birthday.

Why had I let Hendrikus’ Enfield travel tales inspire me and not listened to my friends and colleagues who urged caution?

“What about your pension?” they’d cried when I told them I was giving up my secure career as a health visitor and going off to India with an exciting young Dutchman I’d met there the previous year. I eventually exited the city and was some way to learning that apart from having two wheels, Enfields are not a bit like the Japanese motorbikes I had previously owned.

“What do you mean, I’ve got to change the oil?” I retorted when Hendrikus told me about maintaining this relic of a past age. I’d never as much as picked up a spanner before, taking my Suzuki GS500 for an annual service only once it was warm enough to emerge from the garage. I thought the little tool kit in the side box of the 500cc Bullet was for someone else to use, along with the manuals.

Sorting out documents was a lengthy, frustrating paper chase from one end of Chennai to the other and back again. In the end, fifteen signatures from five different departments had been required to take possession of my Enfield.

I had a crash bar, luggage racks for my soft bags, and car horns fitted, and paid extra to have the Enfield painted black. Standard with the bike were lifelong road tax for Tamil Nadu and ladies’ handles for sari-clad women pillions to hold onto, necessary for the families of up to five we saw on one motorcycle. I quickly had to unlearn modern bike foot controls. Not only was the gear-change lever on the right where the back brake should be, but the gears were ‘First up, all the rest down’. It gradually dawned on me that a huge part of travelling with this thing was the thing itself. Keeping it happy took up a good deal of the time. I’m an ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ woman. Hendrikus was an avid if not obsessive maintenance man. Even when I knew I’d only run out of petrol he wanted to strip the carburettor. I had to put my foot down sometimes but actually found the work of identifying and fixing problems fun and challenging, although if I’d been told before just how much attention it required I would probably have gone for a different motorcycle. It was a good way to learn how a single cylinder four stroke works as he insisted I watch and help whenever jobs needed doing.

In March 2000 we left Chennai. Being on tight budgets we stayed in cheap hotels or once plush but now faded Government Resthouses. We slept by rivers, in parks or off-road in orchards. Twice my bike fell on me during the night as I slept beside it in mango groves so I learned to tie it to a tree to stop being squashed and soaked by petrol. I fell in love with the bike, India, and, after almost fifty years’ regimented normality, a blissfully unstructured and aimless life.

I developed a ‘travel grin’ of childish contentment. On quiet roads I would ride side-saddle or stand on the saddle with one leg out behind me, or cross my hands on the handlebars operating the throttle with my left hand enabling hand-holding with Hendrikus. He held sweets out for me to grab as I went past chugging on deserted roads. Sometimes the throttle cable stuck so riding with arms folded was fun. We rode without helmets whenever possible, rarely going faster than 40mph (the road conditions not allowing for much more). We had no need to hurry and could talk to each other as we tootled along. I could feel the warm wind, hear the engine, smell the aromas and taste the dust of India and see all round. For me, it was worth the risk.

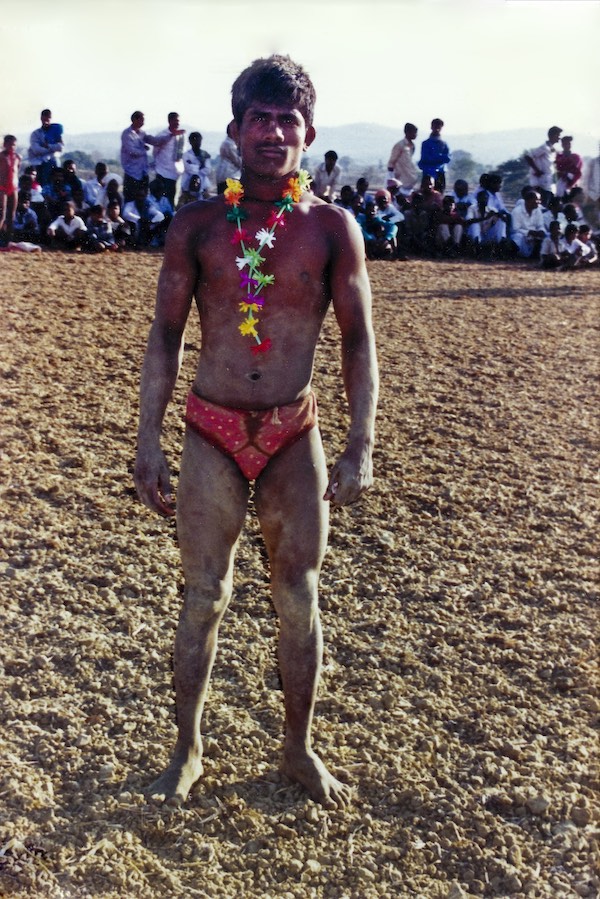

We passed villages made of mud houses with thatched roofs and watched a village wrestling match where the competitors wrestled in their underpants in a dusty field. We joined in cricket games with the boys and went to markets for food and entertainment. I had my silver ring turned into ‘gold’ and my fortune told by a parrot who picked a card with its beak. I learned to enjoy chai, the sweet, milky tea which had made me retch in Asian homes when I was a health visitor. We ate street food and drank tap water as Indians do. Every day was an adventure. Sometimes we would travel as little as 50 kms before finding a place we couldn’t bear to pass. Other times we’d ride all day, stopping only for food and drink. Often we washed and cooled off in a river or water tank, joining local children with their water buffalo or camels. People were friendly and interested in us as we rode on country roads strewn with millet drying in the heat, where most foreigners don’t go. This is the real benefit of having your own transport. I’ve backpacked and travelled by bike. Backpacking is harder work. Everything has to be carried, bus and train times and tickets obtained. With a motorbike, you just sling all your luggage on the bike and go where and when you like, avoiding running into unwary people and animals, and enjoying roadside views, fruit and drinks. Just Heavenly! We always found petrol when we needed it.

India is noted for its bad roads and poor driving standards. I crashed into ditches to avoid dithering scooters and bicycles. The main roads can be awful with potholes and heavy, dirty traffic. In cities, traffic flows like water, a rather good system. Vehicles inch themselves into the flow, everyone shuffles to make room. Away from the cities, on the little roads, there is local agricultural traffic, huge hay loads, herds of goats or even ducks to contend with. A duck-keeper shepherded a thousand or so ducks to a large pond for their daily swim while we parked the bikes to watch them.

I never felt unsafe in India. Only when we had to sleep on a pavement in Calcutta one night and I woke to find someone trying on my glasses did I feel anyone would rob me. Yes, curious locals would surround us when we stopped for a fruit juice or for fuel, and fiddle with the Enfields’ levers and switches but luggage was left untouched on bikes for hours whilst we went to explore.

We went to Andhra Pradesh because Hendrikus wanted to do an IT course to help him get a job. After riding through a nature reserve, we stayed in Hyderabad for three weeks in a cheap room which flooded every time it rained. I breakfasted on delicious masala dosa with fresh mango and learned to ride my bike on my own through crowded streets, avoiding speed bumps, chickens, people and cows. I also took the opportunity to have some dental work done and have a haircut at a Muslim beauty parlour where the women took off the outer wrappings to reveal fashionable clothes beneath.

Battling with mosquitoes was an anticipated way of life. A spider in my sleeping bag wasn’t and I was left with tiny fang marks on my leg and the feeling that a cigarette had been stubbed on it. Scorpions like spending the night in boots. Frogs are soothing when you are sleepy at dusk after a day’s motorcycling if you don’t want a conversation without shouting over the croaking.

In Orissa, a rickshaw darting in front of me made me wobble and fall off. It was then I noticed primer under the black paint where I had a scratch on the tank. I had paid extra to have a grey bike painted black and had been well ripped off for a non-existent paint job. I laughed. It is all you can do in India, there being no point in getting wound up about anything.

It was so hot, my contact lenses almost became welded onto my eyeballs and after a lunch stop I returned to the bike and had nasty burns on the inside of my fingers when I pulled in the clutch lever. Sweat dripped off my nose even when I wasn’t doing anything. Mending punctures from fiendish thorns or discarded nails in blazing sun wasn’t much fun but generally I loved the heat.

River-crossings were plentiful and although I managed to keep the bike going through deep, rocky ones and skilfully negotiate awkward tracks, I’d occasionally fall off at the simplest obstacles. I hit a patch of sand and crashed, going flying into a hedge. At last Hendrikus had his wish to explore the carburettor when I kept stalling. A rubber washer in the choke had perished leaving it on permanently. A bit of inner tube did well as a replacement and is still there. We entered Puri at festival time when the god Jagannath is paraded around the streets and huge wooden chariots are made – from whence comes the name ‘juggernaut’. Here, also we saw a little hole in a wall where customers were furtively buying hash.

My bike had a service in Enfield-mad Cuttack in a brand new workshop which was blessed before the procedure with incense sticks and prayers.

We were now on the border between West Bengal and Bihar and had found a dhaba, a roadside restaurant truck stop where we would stay the night, under a canopy outside on charpois, wooden beds strung with …well, string! They had run out of beer and we were directed to a nearby off licence across the border. Hendrikus came on my bike with all my luggage and we approached the checkpoint. The police officer wanted an astronomical amount for letting us through even though we said we would only be a few minutes. So I rode round the barrier and went on. After we’d bought our beer, heavy rain reduced visibility and my bike stalled at the barrier on the way back. As my police friend angrily approached I kicked and kicked the starter which was hard with Hendrikus on the back. Finally I was successful and rode off again at his raised fist. It would have been a most expensive beer if he’d caught me. The rain was torrential that night and in the morning the friendly manager said, “God has washed your motorbikes!”

We left the area with its dead dogs, goats and overturned lorries at the roadsides and made our way to Darjeeling which was like being in a different country. We had to stop and cool the bikes after low gear climbing for hours. Sikkhim was different again and we saw Kanchenjunga in the distance, the world’s third highest mountain. Even though I had no carnet de passage (vehicle passport) I was allowed into Nepal and the ride to Kathmandu (one of my favourite five roads) was thrilling as I swung from left to right on the bends, up and down mountains. Nepal has a reputation for being slightly less whacky than India but here I saw a naked woman walking along a road as if it were quite the normal thing to do.

It was inevitable that at some point Hendrikus and I should lose each other. On a road to Delhi we each thought the other was in front. Fortunately we had already chosen a guesthouse there, either waiting until the other turned up. My clutch cable broke and as I started to replace it, two local chaps turned up to help. They snatched the spanners from me saying, “No Madam, we must arrange this for you”. They sent a man to the local Enfield mechanic who came within minutes and the job was done. They then invited me to stay with them when I explained I had lost my partner. They took me out for a meal and gave me the best bedroom to sleep in. I found Hendrikus the next day at the Delhi guesthouse. My first experience of travelling alone had been a success.

Whilst waiting for my carnet to be arranged ready for Pakistan, we went to Kashmir with its armed Indian soldiers on every corner. On Srinagar’s lake, we stayed in a houseboat, which, to access with the bike, I’d had to ride up a flight of steps, stopping smartly at the top to avoid riding into the lake a metre beyond. We were turned back from the ‘pretty way’ through the mountains back to India as the army had intercepted a message that we had been spotted by the mujahideen in the forest. We had already been under curfew because of an attack on Hindu pilgrims at a festival we had visited only a few days before. The army engineers repaired an oil leak on my clutch case before we left though.

The carnet took ages to arrive and Hendrikus went on to Lahore without me. I stayed at the Golden Temple in Amritsar, one of my favourite buildings; and when the carnet arrived the border crossing into Pakistan went smoothly. We had some vague plan to try to get our bikes into China even though we knew it was highly unlikely. But a trip to the Chinese border would be interesting anyway. As usual, we did anything we could to ride on dirt rather than tarmac but the route we took was as hard as I could do or ever want to do again. We left the Karakoram Highway (KKH) at Naran and proceeded up the Khagan Valley, which for the most part is little more than a goat track. I fell off countless times and once almost dropped over the edge and into the steep valley far below. Sharp jagged rocks littered the track, which was waterlogged when it wasn’t crusty and rutted. I lost items from my luggage as the bike was being bounced and bashed on boulders. Every inch was hard-won, loosening nuts and bolts. I was scared and tired and insisted we camp as cold came with the dusk. In the morning the thermometer showed 5 degrees. An hour later as I washed in a stream it had risen to 48 degrees in the sun. We crossed a bridge with so few planks they had to be shuffled from behind us to in front by a man as we rode slowly across. The track got harder and I lost count of the times I had to tell myself “I can do it!” because I knew there was no going back. We met nomadic people returning to the lower slopes with their sheep for the winter. Unlike in the rest of Pakistan I’d seen, women’s heads were uncovered, the mountain people having their own rules about that. We reached 4366 metres from where we could see Nanga Parbat and began the final ascent to lawless Chilas back on the KKH. Some shortcut! Hendrikus’ front wheel fell off due to a lug snapping. String and cable ties to the rescue! Exhausted, we fell into a good hotel despite the cost. Next morning I gave a man who had five gunshot wounds some pain-killers. He was on his way to Gilgit some distance away as the rival gang who had shot him threatened to kill him at the local hospital. His ambulance was an open truck.

We were destined to have a long stay there ourselves as Hendrikus’ battery was not charging. No Indian spare parts in Pakistan of course, so there was nothing for it, we bought many metres of copper wire and painstakingly wound two new coils using a vacuum cleaner nozzle as a frame for each. It worked and we travelled on to the Chinese border, through the gorgeous Khunjerab Pass where we were stopped by a man on a BMW who was being filmed on his travels. He told us he couldn’t go further due to snow and ice on the road and advised us to turn back. We scoffed at his heated hand-grips and carried on. At the border, after taking tea with the guards, we peeped over the barrier at the stunning snow-topped mountain ranges into China that we could not visit by motorbike. To make up for the disappointment, I slid about on the snow towed by Hendrikus on his Enfield. On the way back, because we were freewheeling to save petrol, we were unheard by a herd of rarely seen Himalayan Ibex, which we observed for some time.

We decided to head west and spend the winter months in the Chitral area eventually moving into Iran from Balochistan when the passes opened again. We were making our way to beat the snow along the Shandur road when I was hit by a cherry red 4WD coming round a sharp bend in the mountain track. With river far below to the right and mountain immediately to my left I had nowhere to go and waited for the inevitable crunch. I knew my leg was broken. I looked down and my right foot was facing backwards. I reached down and felt the grinding of bone as I turned it to the front. A compound fracture meant a return by plane to Islamabad, flying in about an hour the same distance it had taken us three weeks to cover by Enfield but the view was so stunning it was almost worth it.

Would I go back to Britain or stay in Pakistan? As Browning wrote, “So free we seem, so fettered fast we are!”

Jacqui Furneaux

To be continued…

You can see all of Jacqui’s photographs here:

This article first appeared in The Rider’s Digest issue 140, July ’09