The IJMS Conference, 2024

Are you a biker intellectual?

How many motorcycle books have you got on your shelves? (You’re allowed to include Haynes manuals, Ogri annuals, and that big book of Harleys that you got from your gran.)

If you’ve got more than ten bike books, I reckon you qualify as a biker intellectual. In which case, the IJMS is the club for you.

On the surface, it’s not really a club. The initials stand for the International Journal of Motorcycle Studies. It’s an academic journal, and an annual conference.

But really, it’s a bike club for professional academics. Think of the Journal as a club magazine, only seriously heavy stuff, with peer-reviewed articles and an online archive. Also, at the annual rally, instead of camping in a field with beer and silly games, they take over a college lecture hall, print an agenda, and have several days of lectures and a couple of film shows.

There’s no formal membership, but you’ll enjoy it most if you’ve got a PhD or an MSc. The largest group will have at least one foot in Cultural Studies, a discipline which started in Birmingham in the late ‘60s and has now spread to universities across the world. But the bike thing brings together sociologists, historians, psychologists, literary types, geographers, politics lecturers, art school people – even a few engineers.

How did people get into Motorcycle Studies?

For this you have to understand the academic community – the postgrads who work in colleges and universities, from PhD students to professors and department heads. Obviously, the first aim in life is to do stuff that you enjoy. But after that, you want to get your ideas published in academic journals, because that’s how you build a career.

It turned out that at several Cultural Studies events, people found that as well as being sociologists or film lecturers, they were bikers on the side.

So they developed a cunning plan: to start a proper peer-reviewed academic journal about motorcycle culture. That way, they could talk about bikes AND get into print. The International Journal of Motorcycle Studies began in 2005.

From the beginning, the tone of its articles was high; after all, it’s an academic journal, so you have to use long words. Cultural Studies itself, being a new and insecure discipline, is written in a particularly difficult jargon, and you need to know your way round Husserl, Gramsci, Adorno and Baudrillard. Can you say ‘autophenomenographic methodology’ out loud? And have you any idea what it means? If not, you may need to do the foundation course.

Another feature of an academic career, once you get senior enough, is that you go to conferences on your subject, and get your department to cover the cost of travel. So Step Two of the cunning plan, once the Journal had taken off, was to put together an annual conference, devoted to bike topics. By day, it’s a proper conference with lectures and film shows; by night, it’s a party and a bike rally.

The first two conferences, in 2010 and 12, were at Colorado Springs in the USA – great biking roads, apparently. Other events have been held around the USA, in Alabama, California and Oregon. 2013 and 16 were in London, at Chelsea College of Art.

In July 2024, the Conference was back in England, on the leafy campus at Nottingham, where the Professor Of Political Theory is Mathew Humphrey, also a biker.

The event ran over three days, with lectures for the first two. On the third day, they did touristy stuff such as a visit to the National Motorcycle Museum; I confess that I skipped that, as I needed to be back on the road.

So what did they talk about?

For the first two days, we sat through at least seventeen lectures, and I loved every one of them. But as I said, I’m a biker intellectual: I love this stuff.

To avoid boring the rest of you, I won’t give a blow-by blow account. Instead, here are some of the highlights from my notebook…

Who are the most dangerous riders on the road?

I’ve always thought it was people on stolen motorcycles. Or, riders who are off their heads, and out in the middle of the night. When you see a local newspaper report saying ‘the accident took place at 2.15 am, the rider was under the influence of alcohol and riding a motorcycle not his own’ then several Venn diagrams are intersecting right there.

But I was wrong.

According to Shel Silva, Phd researcher at Bournemouth University, who’s a neuropsychologist and safety activist; based on actual crash figures, collected over several years: there’s one category of rider who are the most dangerous of all.

Middle Aged Motorcyclists. On Performance Bikes. Riding In Groups.

They don’t have small accidents, they have big ones, and when they go down, they skittle their mates as well. And no amount of reflective gear or racing leathers is going to help.

If this is you, you should worry. The stats don’t lie. I felt a cold shiver, literally a week after the conference, when no less than five riders ended up dead, around Buxton, in one summer weekend. Three of them were Ducati riders in their 50s. I thought: “Shel Silva predicted this”.

A further footnote re middle-aged men, riding in groups. After three riders died last summer, in the Scottish Borders, the traffic authorities have just announced a 50mph blanket speed limit on a series of popular biking roads. Consequences.

How many different transport authorities are there in the UK?

One? Thirty? More? Mathew Humphrey, Nottingham’s Professor of Political Theory, knows the answer. One hundred and fifty-five.

Although we have national standards for road signs, driving laws, etc., there are 155 different teams in charge of local speed limits, road design, transport priorities etc.

Each of these 155 teams will produce their own 5-year local transport plan. Typically, it’s not integrated with anyone else. More worryingly, they won’t be using a common set of statistics, either.

Mathew’s team set out to gather these local plans: they haven’t got a complete set, but they managed to get 120 of them, which is a pretty good sample.

There is a saying in planning: ‘things that don’t get counted, don’t count’.

So you may be surprised to learn that, in 10% of the plans they collected, motorcycles were not even considered as an separate mode of transport. Instead they were lumped in with ‘private motor vehicles’ of all sizes and types.

Even the UK Green Party recognises two kinds of motorcycle: bikes over 125cc (which should be banned at once) and those under 125 (which should be phased out in time).

But if bikes don’t even exist as a mode of transport: that’s worse. Because if they’re not transport, what are they? At this point, your local Chief Constable steps forward. From his or her point of view, they’re two things: a lethally dangerous weekend activity, and a facilitator of crime. Ban them, and it makes no difference to transport policy, as they never counted in the first place. And will the non-biking majority step in on our behalf? That depends on our popular image…

Should you throw away your reflective Sam Browne belt?

It was great to see the latest version of Kevin Williams’ ‘Science of Being Seen’ presentation, by Kevin Williams of Survival Skills Rider Training, who also wrote several of the books on my shelf.

The issue is the common SMIDSY accident: ‘sorry mate, I didn’t see you’. Motorcyclists tend to blame the other driver for not looking, not caring, etc, but there are a whole series of factors that make a rider difficult or impossible to spot.

Reflective belts can break up a rider’s outline, like disruptive camo on a warship, so that it actually takes longer to get recognised. Light-coloured gear can make a rider disappear against a light-coloured background. We can’t rely on shiny kit. Maybe we should go back to black.

Kevin’s point is that on top of sorting out our own sightlines, we need to think harder about whether drivers can see us. Or recognise us. Often we should assume they can’t, position accordingly, and cover the brakes.

Personally I fit a big horn and I’m not afraid to use it.

Is it OK to skip bits of ZAAM?

I am of course referring to Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance [Pirsig, 1974]. It’s the core volume in any Biker Intellectual library. If you are a sad case – like me – you might also own the official Guidebook to ZAMM [Disanto & Steele, 1990].

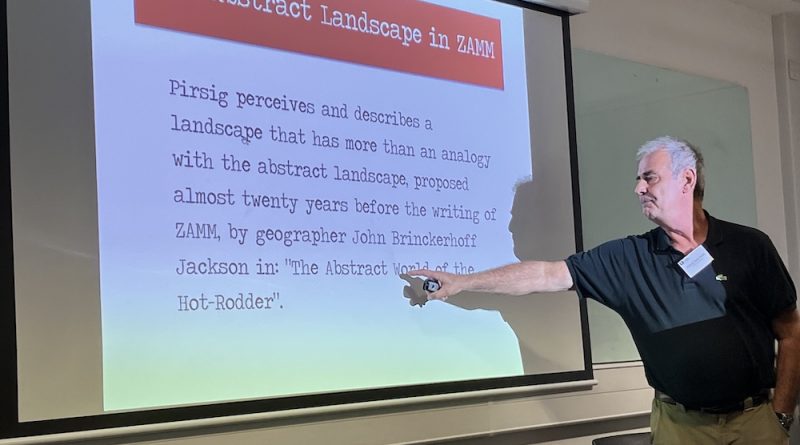

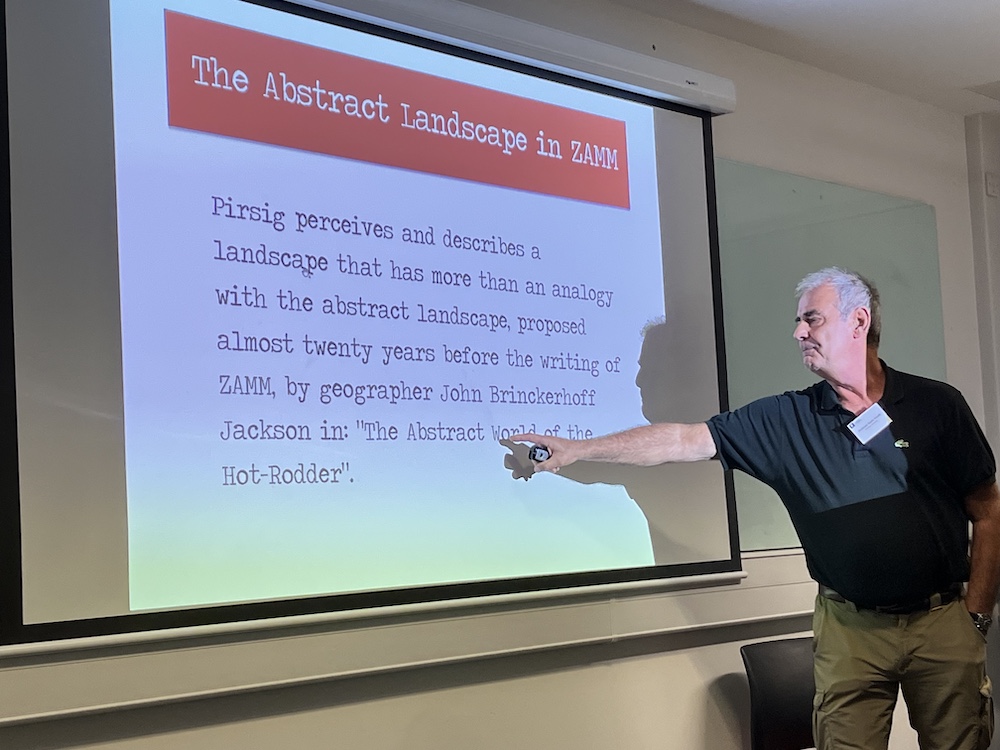

In a daring address, Guido Borrelli, Professor of Urban Sociology at the University of Venice, made the bold claim that some of ZAMM was actually quite boring. Or at least, he felt he could skip quite a lot of it.

After the initial shock, I spotted a few nodding heads around the room.

To be fair, the Professor wasn’t dismissing ZAAM altogether, but deprioritising Robert Pirsig’s metaphysical agenda. Instead, he claimed that in spite of himself [my italics] Pirsig had produced a useful essay on what it means to observe things while travelling on a motorcycle.

Or in his words: “the act of seeing on a motorcycle is a performative act: seeing things as pure seeing, induces us to produce appropriate tropes for deciphering contemporaneity”.

I’ll go along with that.

Does social status make you safer?

It might seem natural to us to see riding a bike in traffic as a matter of physics – sightlines, space, road design, braking distances and all that. But to Professor Yuchiro Kawabata of Kyoto University, the road is also a SOCIAL space. We give way to people we respect; we are less polite to people that we don’t respect.

He found out that in Japan, bike riders were seen as more irresponsible than they actually are; and conversely, bike riders see car drivers as actively hostile, which they aren’t.

I thought – not just in Japan.

The prof went on to say that negative clichés don’t help. They make things worse.

So every time you see someone dicking about in traffic, remember: he’s not just being stupid for himself, he’s lowering the reputation of every motorcyclist, in the eyes of every car and truck driver that he zooms past. And that reduces the level of respect for everyone else on two wheels, including me, Mr Sensible.

And as for all that ‘outlaw biker’ stuff in movies and pop videos – more about that, later.

Can we mash up Girl on a Motorcycle with the 1970s New York art scene, plus Italian radical politics?

We can if we’re reading The Flamethrowers, a novel by Rachel Kushner, which the presenters Caryn Simonson and Sheila Malone are very fond of. I’ve read it too. My reactions are mixed. It’s hard to debate unless you’ve actually read the novel.

But there’s more to a book than the story and the arguments. If it describes your own life, the emotional resonance is unbeatable.

Take, for example, the novelist DH Lawrence. He’s a massive local hero in Nottingham. I’ve met people who choke up at the mention of his name. If you’re a Northerner who, by the power of education, climbed the ladder of the British class system; whose father went down the pit, but now you hang out with the gentry and go to Tuscany or Mexico; then Lawrence is your hero, and on a pedestal. Beyond questioning. He created your identity.

In the same way, if you’re a female biker who cares about art, radical politics, and wild-eyed young men; then The Flamethrowers will ring bells for you. And why not.

Can Ogri tell us anything about environmental politics?

David Thomas is head of Cultural Studies at the University of Murcia, in the south-eastern corner of Spain. He likes motorcycle comic strips: in fact, he’s just written a book about them. [The Ambiguities of European Comic-Book Bikers, Bloomsbury 2024]

The legendary Ogri belongs to history, now: but there are still contemporary comic-strip bikers in European magazines. The great thing about comedy is that it questions everything. In this lecture he concentrated on the environmental movement, and how it plays out in the back pages.

There’s a danger that climate activists are losing popular support. David argues that biker comic strips are the canary in the coal mine. The biker sub-group could have gone either way. On the one hand, young, keen on outdoor life and fresh air, lacking respect for authority. But on the other hand the bikers noticed the nauseating moral superiority, the restrictions on movement, the hypocrisy, and above all the hatred of fun.

The Greens are now facing a push-back; they should have seen it coming. But maybe they don’t read bike magazines.

Is your jacket a work of art?

Tom Cardwell is a painter and a lecturer at Camberwell Art School, and he too has a book out [Heavy Metal Armour, University of Chicago, 2022].

He started by painting on jackets, as many of us have done. Then he moved on to paintings OF jackets, plus the people wearing them.

Now he’s zoomed in closer: his latest work is about two areas of the jacket: the imagery, and the black leather spaces in between. The wings, the wheels, the skulls, are part of a long Momento Mori tradition in European art going back to the Romans; the black but textured spaces are related to Abstract Expressionist black canvases.

So: paint your jacket, or don’t paint your jacket: either way, you’re making a statement.

Can the right gang replace the wrong gang?

Perhaps the way to break urban gang culture, with its grim death rate, is to create an alternative gang culture with the same rewards and hierarchies, but different tools: gain status by jumping a bike through a hoop of fire, rather than by stabbing someone outside the chip shop.

We had a talk from the great Roy Pratt, MBE, who founded the IMPS motorcycle display team back in 1970 – 54 years ago!

Originally they were doing country holidays for children from poor backgrounds; but they found a couple of old Bantams in a farm shed, and things went downhill from there.

They went on to form a display team based on the Army’s White Helmets, and since then thousands of children have trained with them, and gained a sense of purpose and identity. It’s clear that they’ve done a great job.

The challenge would be to scale the formula outside their Romford base, and that’s hard. It’s not Roy’s fault, but the Army is now desperately unfashionable as a rôle model. The Signals have stopped riding bikes and use diesel quads instead: the display team is long gone. Around the country, other people have started bike-based youth schemes as an alternative to gang culture: but most have failed. It takes energy, cash, and a bike-friendly local authority. The third is hardest to find.

Is there a crisis around fatherhood as an identity? Are motorcycles involved?

By coincidence, two different presenters from the USA gave autobiographical accounts of father figures in their lives; how much these men mattered, and how they channeled fatherly advice via motorcycle activities. One, about how to build and maintain Vincents. The other, about how to avoid getting killed on the road.

(Put your hand down at the back: I know that the motorcyclist’s Bible, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, is also about a father-son relationship. You’re quite right.)

Arguably, there’s a crisis about the representation of fathers in our culture. You’ll notice that the rôle is embedded in the word ‘Patriarchy’. In bringing down the patriarchy, there’s a risk that ordinary non-toxic fatherhood might get squished.

This certainly happens in the world of Disney. I’m not the first to point out that, for the children’s adventure to begin, Father must be dead; or in prison; or a long way away; or a powerless fool. It’s the most infuriating thing about The Barbie Movie. Barbie might reject the clichés of motherhood; but poor Ken doesn’t get the option of fatherhood. It doesn’t exist.

A second observation about our culture, is that women talk directly to each other: but men talk side by side, while looking at something else. The ‘something else’ might be a sports team, or making something, or playing a game. It’s indirect.

That’s where bikes fit in. Both speakers wanted to respect and value these father figures, who taught them something essential about how to live. But rather than addressing them directly, which would be embarrassing, we thank them for showing us how to assemble an engine, or how to ride safely. That makes sense.

Should I give all my old bike books and mags to the VMCC?

Yes! Is the answer from the VMCC’s librarian, Annice Collett.

Some of us – you know who you are – keep back numbers forever. We might be running out of space. Or, we could be doing a house move, and ask ourselves whether we need twenty cardboard boxes full of The Old Stroker, at the back of the garage. Isn’t it time they went to the tip?

Annice at old us that she has room for the lot. Sorted or unsorted, part runs, one-offs, old event programmes: as long as it’s bike related, she’ll take it in, as long as it covers bikes more than 25 years old.

She gave us some stats. At present they have 960 magazines, 8000 programmes, and the factory records for BSA, Norton, Triumph, and Scott. These occupy more than ⅓ of a mile of shelving. Most museums are short of space: but the VMCC Archive has room for more.

Some people I know have shedloads of stuff. So I asked her, at question time: “are you serious?”

Apparently so. She loves going through old cardboard boxes. So, if you want to free up a couple of rooms, just contact the VMCC librarian. Tell her I sent you.

Where shall we ride next year? And on what?

I’m sure you’re all familiar with the concept of ‘the male gaze’. It’s a staple of feminist art criticism, invented by the art critic John Berger in the 1970s (a biker, by the way).

Variants have followed: such as The Tourist Gaze [Urrey & Larsen, 2011], which explores the same theme of power imbalance.

So how do we avoid The Tourist Gaze? This is the question asked by Jason Wragg, FRGS, who teaches Outdoor Adventure Leadership at the University of Lancashire.

The most ethical option, and also the most environmentally sound, is to stay at home and not go anywhere.

But if you’ve already decided to burn a ton of aviation fuel, and then turn up in someone else’s country and ride on their roads, how can you offset the burden of guilt?

The solution, according to Jason, is not to arrive on a big BMW bristling with technology; try something closer to the ground.

He followed this philosophy on a tour of the Western Cape of South Africa, where he hired an Enfield Classic.

Instead of sweeping though villages in a cloud of dust, he puttered along at Enfield speed: so other cars and trucks shot past, and he was the one left behind in the dust.

Although the bike was almost new, bits fell off from the start: so he had plenty of opportunities to practice his repair skills with baling wire and tape.

Instead of taking him to obvious tourist sights, the bike imposed its own agenda. He saw the inside of many small repair shops, where he had the opportunity to reset the economic imbalance by transferring money to local mechanics, taxi firms and boarding houses, while waiting for spares to arrive.

All of this was recorded not by the typical online blog, but in comic-strip form, which Jason calls ‘autophenomolographic methodology’.

Anyway, where next?

As another way of avoiding being a mere tourist, Jason’s thinking of Iceland, which also has rough roads: but fortunately the local people are just as rich as we are, so there’s no economic imbalance to worry about. In fact there aren’t many people anyway: you can’t have a ‘tourist gaze’ if there’s no-one to gaze at. Also you can hire BMWs and Hondas, but no Enfields. As a result, there’s less chance of getting stranded. It might be a good place for the next IJMS conference.

What went wrong at Vincents?

We watched Speed is Expensive, an excellent biopic about Phil Vincent, made by David Lancaster. A career in two halves: the first stage as an innovative, uncompromising designer; the second half as an increasingly cranky tyrant who alienated the best people in his team, and had no succession plan. I detect a pattern in human behaviour. Fill in your own examples.

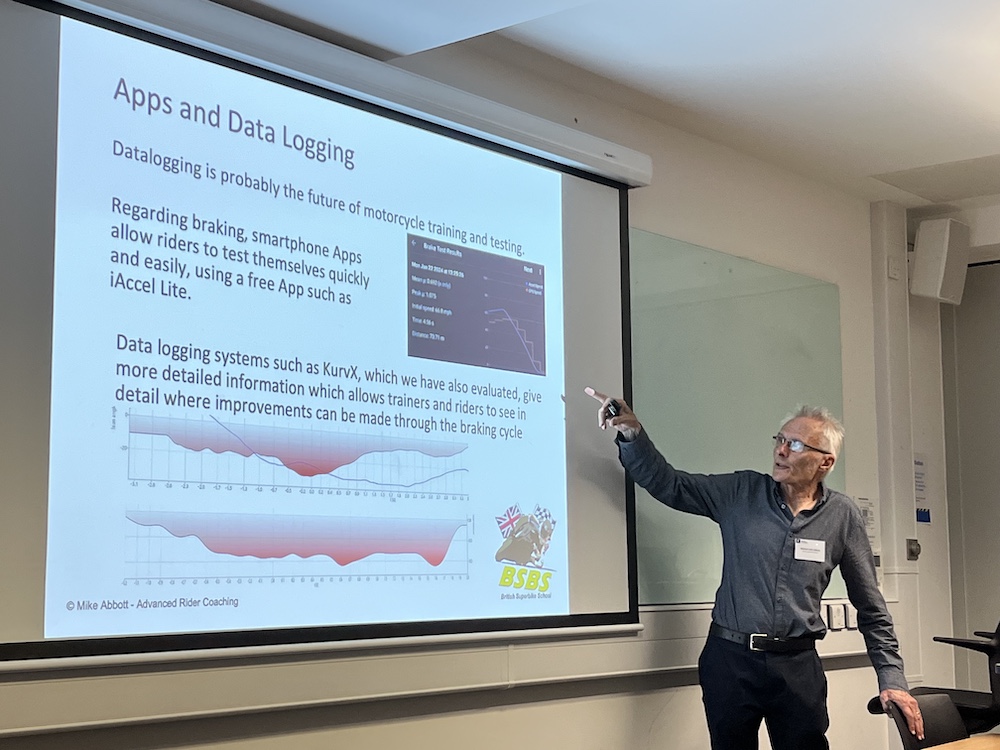

How hard can you brake without falling off?

Mike Abbot is a trainer and a safety expert, and he’s on a mission to improve our braking skills. He’s been collecting bike accident data, based on skid marks, and accident damage, and has reached some surprising conclusion.

“50% of riders can’t brake hard enough to achieve Highway Code Stopping distances.”

“50% of riders in accidents skid and fall”.

Either way, it looks as if half of us are rubbish at braking. Also it’s not related to experience.

This worried me, as I think of myself as an experienced rider. I run with a large ‘safety bubble’; I choose the best sightlines; I hardly touch the brakes. I can’t remember the last time I triggered the ABS, and if I do, I’ve made a mistake in planning, and got something wrong.

As a result of all this common sense, I’ve had almost no practice in hard braking: perhaps I’m not safe!

I resolved to go out and practice heavy braking, but then Mike gave another piece of advice: “don’t practice on your own”. I can see his point. I’d better sign up for a course.

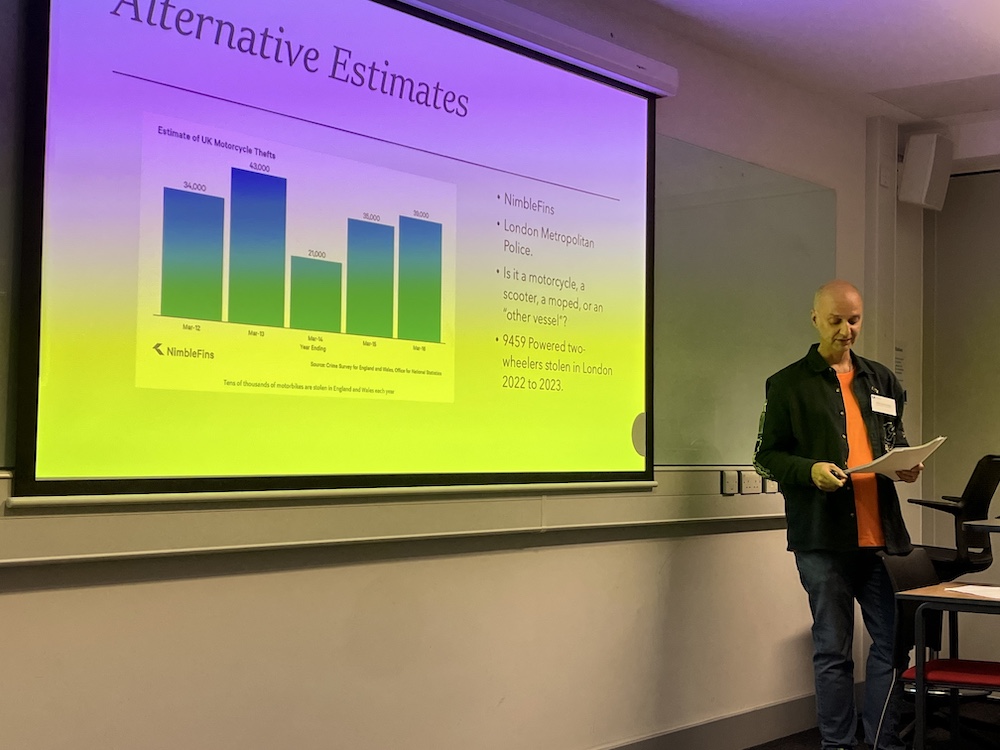

Is the risk of theft putting people off biking?

Alex Parsons-Hulse, who’s a BMF council member, has been conducting research into the barriers that prevent people in the UK from using motorcycles as basic transport.

Apparently, 64% cite ‘fear of theft’ as a major barrier, while for a massive 81%, ‘improvements to security’ are their FIRST priority when suggesting improvements to motorcycle design.

Let that sink in. Not higher speed, or better economy. What we need is more protection against getting the bike nicked.

That’s the impact of Britain’s thieving community on motorcycling as a whole.

And is your local Chief Constable worried about this? Any sense of crisis? Or even the slightest concern?

It is, of course, a matter of targets. As Matthew Humphrey pointed out in his lecture: in some local authorities, bikes aren’t even counted as a transport category. So the epidemic of bike theft makes no difference to transport policy.

On the other hand, as Shel Silva noted in her lecture, there’s another epidemic that IS being noticed: middle-aged idiots on sports bikes, crashing in groups.

So if you wonder why it’s so hard to get any interest in your stolen bike, but so easy to get done for speeding: it’s policy, measured by targets, based on stats.

Are we sick of Biker Gang mythology?

My favourite lecture of the weekend, delivered by Eryl Price-Davis, who’s a former DR and career academic, who now keeps his hand in as a trainer and long-distance tourer.

He started calmly enough, putting us in our place.

‘Motorcycle Studies’ has gone off course: we think it’s all about us. But we’re not representative of the world. We’re a tiny minority.

In terms of absolute numbers, even the USA is only the 14th largest motorcycle market in the world. The UK is the 37th: behind Burkina Faso, Guatemala and Mongolia.

Not only that: we, the typical attenders at an IJMS conference, are a minority among motorcycle riders. We ride comparatively big bikes. We’re ‘leisure riders’. But we’re vastly outnumbered by the majority, even in the UK, who ride simply as basic transport or food delivery.

Now in the early days of Cultural Studies, ‘subcultural theory’ was all the rage. According to the progressive agenda, gangs of all kinds, including biker gangs, were seen as working class heroes, fighting against conformism and capitalism, Sticking It To The Man.

But in romanticising these people: did we made a huge mistake?

As I said, this was the most passionate lecture of the weekend. The phrase ‘outlaw wankers’ is underlined in my notebook. Other terms used included racism, sexism, misogyny, homophobia, and antisemitism. ‘Nothing more than fronts for organised crime, sex trafficking, gun crime, murder and rape… we shouldn’t be aping them or celebrating their ‘style’… these arseholes need to be condemned not lauded’.

Don’t hold back, Eryl. I said this was going to be fun!

Any conclusions to the conference? Was there a theme?

It doesn’t look good, does it.

The vast majority of sensible, practical, working motorcyclists are being overlooked both in transport planning and popular culture.

A small minority of clowns, idiots and wankers are getting themselves noticed out of all proportion: both in the accident stats, which the cops care about, and in popular perception, which drags us all down.

And on that cheerful note – I recommend the IJMS to all intelligent readers, available online, including most of the back numbers. Also I’m looking forward to the next conference, whether it’s in Colorado or Iceland. Just have to get there, with a bike.

Andy Tribble

Dave Gurman’s write up of the 2013 IJMS is available HERE